-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Joyce Tai, DVM, MS

By Joyce Tai, DVM, MS![]()

angell.org/dentistry

dentistry@angell.org

617-522-7283

April 2022

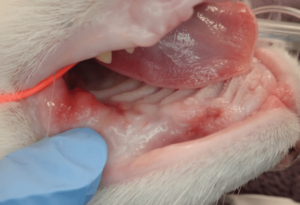

Feline chronic Gingivostomatis (FCGS) is a debilitating immune-mediated oral disease characterized by marked oral inflammation. It has a prevalence of up to 12% in the domestic feline population.3, 7 Clinical characterization includes ulcerative and proliferative appearances of the oral mucosa. Differentiation from severe periodontal disease is defined by  inflammation in edentulous regions of the oral cavity such as the palatoglossal folds and sublingually. Clinical signs of FCGS include hyporexia, hissing at food, weight loss, pain/sensitivity around the face, decreased activity, reclusiveness, and decreased grooming. If marked weight loss occurs, FCGS can be life-threatening and warrants urgent intervention.

inflammation in edentulous regions of the oral cavity such as the palatoglossal folds and sublingually. Clinical signs of FCGS include hyporexia, hissing at food, weight loss, pain/sensitivity around the face, decreased activity, reclusiveness, and decreased grooming. If marked weight loss occurs, FCGS can be life-threatening and warrants urgent intervention.

Multiple causes have been proposed for FCGS, but no single etiopathogenesis has been proven. The disease has been associated with feline calicivirus, herpesvirus, feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus, various bacteria, tooth resorption, multicat households, environmental stressors, and hypersensitivity. Despite what the root cause of FCGS may be, the disease is considered to be immune-mediated inflammation.

Treatment for FCGS involves surgical intervention though many cats may still require some medical interventions. Surgical treatment involves partial to full mouth extractions with multiple studies reporting marked improvement to complete resolution of FCGS in 60-80% of treated cats.3 If inflammation is still present 1-4 months post partial mouth extractions, full mouth extractions should be considered. Appropriate pain management should be used at all times regardless of treatment modality.

As FCGS is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease, medical management focuses on immunosuppression or modulation. Options include corticosteroids, cyclosporine, recombinant feline interferon omega, and stem cell therapy though each holds risks and benefits. Prednisolone is often used as a fast-acting and effective anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant. Long-term use should be considered with caution due to its many side effects. However, a brief tapering course of managing symptoms can be beneficial.

As FCGS is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease, medical management focuses on immunosuppression or modulation. Options include corticosteroids, cyclosporine, recombinant feline interferon omega, and stem cell therapy though each holds risks and benefits. Prednisolone is often used as a fast-acting and effective anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressant. Long-term use should be considered with caution due to its many side effects. However, a brief tapering course of managing symptoms can be beneficial.

Cyclosporine is a promising immune suppressant that targets T-cells and is generally well tolerated. In one study, 4 of 8 cats (50%) saw clinical remission with cyclosporine alone and no extractions. A second study looked at 9 cats given cyclosporine given post-extraction and saw 77.8% of cats improved over the 6-week study period. Long term, 11 cats were monitored, and 5 (45.5%) showed clinical remission, with the 6 remaining on cyclosporine.5

The use of autologous mesenchymal stem cells is promising though this treatment is not widely available. Similarly, feline recombinant interferon omega is not easily accessible in the US, and studies on its efficacy are conflicting.1

FCGS can be a debilitating oral disease that interferes with a cat’s quality of life. Appropriate analgesia should be used at all times during treatment. Either full or partial mouth extraction should be considered followed by medical management as indicated by the clinical response.

References

1. Arzi B., Mills-Ko E., Verstraete F.J.M. Therapeutic efficacy of fresh, autologous mesenchymal stem cells for severe refractory gingivostomatitis in cats. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5(1):75–86.

2. Dowers K.L., Hawley J.R., Brewer M.M. Association of Bartonella species, feline calicivirus, and feline herpesvirus 1 infection with gingivostomatitis in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2010;12(4):314–321.

3. Hung, Y.-P., Yang, Y.-P., Wang, H.-C., Liao, J.-W., Hsu, W.-L., Chang, C.-C., & Chang, S.-C. (2014). Bovine lactoferrin and Piroxicam as an adjunct treatment for lymphocytic-plasmacytic gingivitis stomatitis in cats. The Veterinary Journal, 202(1), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.06.006

4. Jennings, M. W., Lewis, J. R., Soltero-Rivera, M. M., Brown, D. C., & Reiter, A. M. (2015). Effect of tooth extraction on stomatitis in cats: 95 cases (2000–2013). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 246(6), 654–660. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.246.6.654

5. Lee, D. B., Verstraete, F. J. M., & Arzi, B. (2020). An update on feline chronic gingivostomatitis. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 50(5), 973–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2020.04.002

6. Lommer, M. J. (2013). Efficacy of cyclosporine for chronic, refractory stomatitis in cats: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical study. Journal of Veterinary Dentistry, 30(1), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/089875641303000101

7. Lommer, M. J., & Verstraete, F. J. (2001). Radiographic patterns of periodontitis in cats: 147 cases (1998-1999). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 218(2), 230–234. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.2001.218.230

8. Peralta S., Carney P.C. Feline chronic gingivostomatitis is more prevalent in shared households and its risk correlates with the number of cohabiting cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2019;21(12):1165–1171

9. Rodrigues M.X., Bicalho R.C., Fiani N. The subgingival microbial community of feline periodontitis and gingivostomatitis: characterization and comparison between diseased and healthy cats. Sc Rep. 2019;9(1):12340.

10. Thomas S., Lappin D.F., Spears J. Prevalence of feline calicivirus in cats with odontoclastic resorptive lesions and chronic gingivostomatitis. Res Vet Sci. 2017;111:124–126.

11. Vercelli, A., Raviri, G., & Cornegliani, L. (2006). The use of oral cyclosporin to treat feline dermatoses: A retrospective analysis of 23 cases. Veterinary Dermatology, 17(3), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3164.2006.00514.x

12. Winer, J. N., Arzi, B., & Verstraete, F. J. (2016). Therapeutic management of feline chronic gingivostomatitis: A systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2016.00054