-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

![]()

By Martin Coster, DVM, MS, Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists

By Martin Coster, DVM, MS, Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists

angell.org/eyes

ophthalmology@angell.org

617-541-5095

April 2025

x

x

x

Introduction and Terminology

Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis (GRPU) is presumed to be a hereditary eye disease afflicting Golden Retriever dogs, possibly as early as 1.751 to 3 years of age,2 but generally considered to develop between 4.5 years and 14.5 years.3 Up to 23.9% of Golden Retrievers may be affected after 8 years of age.4 Most dogs are affected in both eyes, although the onset can be asymmetric.

Due to historical descriptions reported as the disease was emerging, it is sometimes interchangeably referred to as Golden Retriever Uveitis (GRU),3 Pigmentary Uveitis (PU),3, 5 and Pigmentary/Cystic Glaucoma (PCG).1, 6 As of the time of this writing, GRPU seems to be the most accurate descriptive name,4, 7 as the disease manifests with dispersion of pigment within the eye and symptoms of internal ocular inflammation (uveitis). Dogs often become blind and experience pain from glaucoma (high pressure), which is considered to be from the effects of inflammation and accumulation of pigment and other substances within the eye. However, even though these eyes appear outwardly inflamed, when histopathology is performed on them, the inflammatory component is typically quite minor.2, 5 It is unclear whether this is due to the effects of treatment or a feature of the disease. It is also essential to distinguish GRPU from other causes of uveitis, such as neoplasia (e.g., lymphoma) and infectious disease (e.g., Ehrlichia canis), beyond the scope of this review.8

Diagnosing GRPU

A progressive, insidious disease, GRPU often causes blindness of both eyes due to the effects of glaucoma at its end-stage. Earlier diagnosis requires careful ophthalmologic examination. The Golden Retriever Club of America’s (GRCA) Code of Ethics requests that all Golden Retrievers that have been bred have annual eye examinations by a board-certified veterinary ophthalmologist for their entire lifetime, from two to three years of age.9 It is also recommended that all Golden Retrievers be examined by an ophthalmologist annually due to the prevalence of GRPU.

The mode of inheritance of GRPU has been narrowed down by pedigree analyses to either autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance or polygenic inheritance.1 In other words, the condition is considered hereditary. It can be passed on in the genetic code as a dominant gene or multiple genes, but the disease may skip generations. The incidence of GRPU has likely been increasing over the past few decades. Since affected dogs do not develop the disease until after breeding has typically occurred, it has been very difficult to select against GRPU in breeding programs.

No genetic test is currently available for GRPU, but research is ongoing. Blood samples for DNA analysis from any affected dogs, and posthumous donations of eyes (along with a DNA sample) from normal-eyed Golden Retrievers 12+ years old, can be submitted to Dr Townsend at Purdue University.10 To help support ongoing research efforts, any owner can also choose to have their dogs’ DNA banked at the OFA’s Canine Health Information Center (CHIC) DNA Repository (blood or cheek swabs) for a minimal fee.11

Key features of GRPU include uveal cysts (not necessarily diagnostic for GRPU on their own), radial lens pigmentation, fibrinous debris in the anterior chamber, iris-lens adhesions (posterior synechia), cataract formation, glaucoma, and eventual blindness.

Cysts

Figure 1 – Solitary thin-walled cyst in the left eye of a Golden Retriever. Note the cyst is transilluminated, with the green tapetal reflection shining through. There is also an incidental wedge-shaped cataract at the medial aspect of the lens. This eye was NOT diagnosed with Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis.

Uveal (or iris) cysts may be present as an incidental, insignificant finding in Golden Retrievers (Figure 1). Cysts must be distinguished from other pigmentary changes such as pigmentary neoplasia (e.g., melanocytoma or melanoma). Just because a Golden Retriever has cysts does not mean it has GRPU. However, the presence of any cystic change within Golden Retriever eyes should warrant more cautious monitoring, perhaps more frequently than annual eye exams. One study showed 61.5% of cases with thin-walled cysts progressed to GRPU within one year.1 It has been postulated that dogs with thin-walled cysts are more likely to develop GRPU than those with thick-walled cysts (Figure 2).

Cysts may be present behind (posterior to) the iris (Figure 3) and may or may not be observable even with dilation. They may be attached to the ciliary body behind the iris or may be found free-floating. Cysts can also be reabsorbed or can rupture, dispersing pigment onto the lens capsule or corneal endothelium (Figure 4). Rarely, cysts may contain blood (hematocysts, Figure 5) or may be associated with intraocular bleeding (Figure 6). Cysts may only be observed using high-frequency ultrasound, but this test is not routinely performed nor recommended for monitoring, as the prognosis for these cysts is unknown.

Figure 2 – Numerous thick-walled uveal cysts in the anterior chamber of the left eye of a Labrador Retriever. This is in contrast to the thin-walled cyst in Figure 1, which is more commonly seen in Golden Retrievers.

The uveal cysts in GRPU are thought to contain hyaluronic acid,2 secreted from the ciliary body epithelium where the cysts arise. This thick substance might be an instigating factor for low-grade inflammation and glaucoma, or may occlude the drainage angle to exacerbate glaucoma. Alternatively, the cysts themselves may mechanically displace the iris forward in some cases, closing the drainage angle to cause glaucoma.

Figure 3 – Numerous thin-walled uveal cysts posterior to the iris of the left eye of a Golden Retriever. This eye was NOT diagnosed with Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis, but cautious monitoring was recommended.

Figure 4 – Thin-walled uveal cyst in the left eye of a Golden Retriever. There is also pigment dispersion on the lens capsule adjacent to the cyst, which is suspected to be from other collapsed cysts. So far, this eye lacks radial pigment, so it is considered at high risk for Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis.

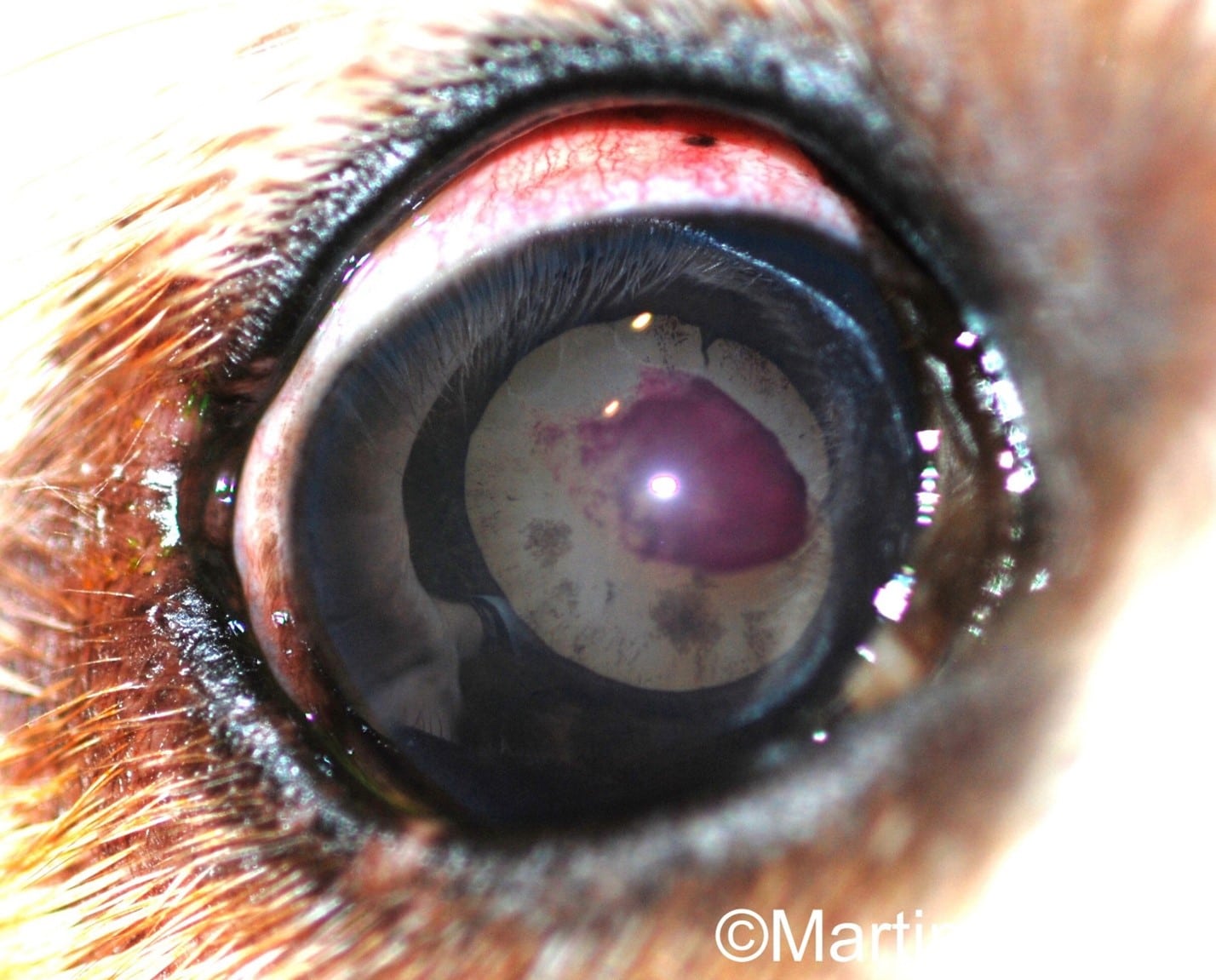

Figure 5 – Cysts, pigment, and a collapsed blood-containing cyst (hematocyst, the red area out of focus) in the right eye of a Golden Retriever diagnosed with Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis, but lacking radial pigment dispersion.

Pigment Deposition

A key diagnostic feature of GRPU is that pigment is deposited onto the front surface of the lens (anterior capsule), in a radial fashion (like the spokes on a bike tire, Figures 6-10). This finding in a Golden Retriever is essentially pathognomonic for GRPU.3, 4 It is possible that the pigment is deposited onto the lens capsule from the iris during normal pupillary excursions, perhaps exacerbated by inflammation or the presence of thicker fibrinous material within the aqueous humor. However, other non-radially-oriented pigmentation can be present. This deposition can occur from collapsed/deflated uveal cysts (and thus, on its own, this pigment would not be diagnostic for GRPU), and adhesions of the iris to the lens (posterior synechia due to inflammation, which may or may not be from GRPU). Pigment can also disperse onto the inner endothelial lining of the cornea, from collapsed cysts either incidentally or from GRPU (Figure 10).

Figure 6 – Radial pigmentation (“spoke-like” deposition) and blood clot on the anterior lens capsule of the right eye of a Golden Retriever with Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis. Cataract is also present throughout the lens. Bleeding is an uncommon feature of GRPU.

Figure 7 – Radial “spoke-like” pigmentation on the anterior lens capsule of the left eye of a Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis patient. There are also larger areas of pigment deposition. Age-related nuclear sclerosis can be seen in the lens. The contralateral eye is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8 – Radial “spoke-like” pigmentation on the anterior lens capsule of the right eye of a Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis patient. Age-related nuclear sclerosis can be seen in the lens. The contralateral eye is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 9 – Dense pigmentation across the anterior lens capsule of the left eye of a Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis patient. Some of the classic radially-oriented pigment is present, along with more prominent, larger pigment deposits. This is likely from a combination of pigment exfoliation from the iris and collapsed cysts. Mild age-related nuclear sclerosis is present in the lens.

Fibrinous Debris in the Anterior Chamber

Figure 10 – Fibrinous strands in the anterior chamber of the right eye of a Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis patient. A deposit of pigment on the inner endothelial lining of the cornea is present, to which the fibrinous material attaches; the pigment is likely a collapsed cyst. Internally, less in focus, is radial pigmentation on the lens capsule. Superiorly, partially obscured by the upper eyelid, is a corneal opacity consistent with degenerative keratopathy (perhaps from the inflammatory disease itself or topical steroid treatment).

The presence of “cobweb”-like cloudy material throughout the anterior chamber is another diagnostic feature of GRPU (Figures 10, 11). Typically, this is found in combination with other signs such as uveal cysts and pigment dispersion. The material could be fibrin, a byproduct of inflammation, or perhaps a protein-rich fluid released by collapsing cysts or even produced by the ciliary epithelium itself. The evidence that this is fibrin comes from the observation that intraocular injections of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) may dissolve the material as it would do to fibrin,3 although other anecdotal reports have suggested no effect.4 Although only 3 cases of tPA injection were reported (in which one developed glaucoma), the present author has found the same clinical effect. As reported, though, some patients will develop glaucoma following tPA injection. For this reason, the present author reserves tPA injections for fibrinous eyes that are already succumbing to glaucoma (and thus, perhaps have little left to lose).

Cataract Formation

Figure 11 – Large fibrinous web-like material throughout the anterior chamber of the right eye of a Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis patient. Haze from generalized corneal edema is present secondary to glaucoma.

Golden Retrievers can have congenital cataracts, a hereditary tendency to cataracts, and/or develop age-related cataracts along with lens haze (nuclear sclerosis) later in life. These conditions are distinct from, and not necessarily related to, the cataracts associated with GRPU. Cataracts in GRPU cases typically start anteriorly, where pigment dispersion and cysts are present, and progression is highly variable. In this author’s experience, GRPU-related cataracts are rarely the sole cause of vision loss (which is due to glaucoma instead). Cataract surgery in GRPU-affected patients has not been reported. It is not recommended by the present author, due to a distinct possibility of surgical failure from inflammation and glaucoma, and the overall poor prognosis of affected cases.

Glaucoma

Ultimately, blindness in GRPU patients occurs from intractable glaucoma.7 In an early report, 50% of cases were blinded within one year,3 but a more recent study showed 13.7% were blind with a duration of glaucoma of 3.8 years.7 This difference is likely due to earlier diagnoses from better monitoring and enhanced understanding of the disease, along with earlier therapeutic intervention.

Fibrinous debris and inflammatory scarring (posterior synechia, where the iris adheres to the lens capsule) are risk factors for the development of glaucoma. High ocular pressure damages the retina and optic nerve, and is usually quite painful, even if stoic Golden Retrievers do not always show it. Squinting, tearing, rubbing at the eye, and appetite and behavior changes should be monitored for. Veterinarians should monitor intraocular pressures (IOPs) routinely in GRPU patients. When detected early, glaucoma may be managed with standard glaucoma drops (dorzolamide and/or timolol). Latanoprost is typically avoided due to its potential exacerbation of inflammation, along with the miotic effects on the pupil — constriction of the pupil may cause pupillary block if the pupil entraps thick fibrinous debris and/or cysts. However, this author will cautiously use latanoprost, with informed client consent, if other treatment modalities are failing.

Treatment of GRPU

It is truly unknown whether therapeutic intervention necessarily controls or slows GRPU. However, given that the disease clinically presents with inflammation, topical anti-inflammatories have been the mainstay of therapy. When GRPU-affected eyes are enucleated and examined histologically, the inflammatory component is minimal, but interpretation is limited since most have already been treated.2 Topical steroids such as prednisolone acetate and dexamethasone (given in the formulation of Neomycin-Polymyxin-Dexamethasone to ensure penetration into the eye) are typically recommended. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been postulated to potentially increase eye pressures, and so are typically avoided.3 However, this author will use topical NSAIDs (diclofenac or flurbiprofen) when the response to steroids alone is not enough (with cautious IOP monitoring) or if corneal ulceration/infection precludes using a topical steroid. No difference in GRPU progression was noted in a small sample size of cases on a steroid compared to NSAIDs.7

Management of glaucoma, as previously described, is paramount once IOP elevates above normal values. Dietary supplementation of an oral antioxidant formulation (e.g., Ocu0GLOTM, Animal Necessity) has been reported, but the effects are unknown.7

As already discussed, intraocular (intracameral) injections of tPA may dissolve the fibrinous material, but it often re-forms within three to six months, and sometimes the injection is associated with a profound exacerbation of glaucoma.

Surgical interventions for GRPU are limited. In painful, blinded, glaucomatous eyes, enucleation is warranted and considered the standard of care. The present author has also had success with intraocular gentamycin injections to cease intraocular fluid production and hence control glaucoma, but this procedure is not usually used in other inflammatory glaucoma patients due to the potential for ongoing painful inflammation.

Conclusion

Golden Retriever Pigmentary Uveitis is a devastating disease causing glaucoma and blindness in Golden Retrievers, especially in advanced age. Many will have to be enucleated to control their pain. However, with better understanding and monitoring for the disease, along with early interventional treatments, the prognosis may be improving. There remains a great deal we do not yet know about GRPU. The disease does not yet have a cure, and its best hope is the development of a genetic test. With genetic testing, more selective breeding can occur to hopefully eliminate the disease from the Golden Retriever population.

x

This article is dedicated to Jack, Oliver, Remington, and all other dogs battling GRPU.

x

Disclaimers: This article is an original summary of peer-reviewed, published data, written through the lens of the author’s 20 years’ experience in clinical veterinary ophthalmology practice. No Artificial Intelligence was used in the preparation of this manuscript or images. Images have been cropped and enhanced with simple brightness, contrast, and sharpness adjustments to better show pertinent details, and copyright watermarked, but no other edits have been made. All rights are reserved; permission to harvest the text or images in this article for AI training or other uses is NOT granted.

x

x

References

- Holly VL, Sandmeyer LS, Bauer BS, Verges L, Grahn BH. Golden retriever cystic uveal disease: a longitudinal study of iridociliary cysts, pigmentary uveitis, and pigmentary/cystic glaucoma over a decade in western Canada. Vet Ophthalmol. 2016 May;19(3):237-44. doi: 10.1111/vop.12293. Epub 2015 Jun 29. PMID: 26119416.

- Deehr AJ, Dubielzig RR. A histopathological study of iridociliary cysts and glaucoma in Golden Retrievers. Vet Ophthalmol. 1998;1(2-3):153-158. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-5224.1998.00018.x. PMID: 11397224.

- Sapienza JS, Simó FJ, Prades-Sapienza A. Golden Retriever uveitis: 75 cases (1994-1999). Vet Ophthalmol. 2000;3(4):241-246. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-5224.2000.00151.x. PMID: 11397310.

- Townsend WM, Huey JA, McCool E, King A, Diehl KA. Golden retriever pigmentary uveitis: Challenges of diagnosis and treatment. Vet Ophthalmol. 2020 Sep;23(5):774-784. doi: 10.1111/vop.12796. Epub 2020 Jul 8. PMID: 32639654; PMCID: PMC7540390.

- Townsend WM, Gornik KR. Prevalence of uveal cysts and pigmentary uveitis in Golden Retrievers in three Midwestern states. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013 Nov 1;243(9):1298-301. doi: 10.2460/javma.243.9.1298. PMID: 24134580.

- Esson D, Armour M, Mundy P, Schobert CS, Dubielzig RR. The histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics of pigmentary and cystic glaucoma in the Golden Retriever. Vet Ophthalmol. 2009 Nov-Dec;12(6):361-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2009.00732.x. PMID: 19883466.

- Jost HE, Townsend WM, Moore GE, Liang S. Golden retriever pigmentary uveitis: Vision loss, risk factors for glaucoma, and effect of treatment on disease progression. Vet Ophthalmol. 2020 Nov;23(6):1001-1008. doi: 10.1111/vop.12841. Epub 2020 Nov 2. PMID: 33135836.

- Massa KL, Gilger BC, Miller TL, Davidson MG. Causes of uveitis in dogs: 102 cases (1989-2000). Vet Ophthalmol. 2002 Jun;5(2):93-8. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-5224.2002.00217.x. PMID: 12071865.

- Golden Retriever Club of America, Pigmentary Uveitis Alert. https://grca.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/GRPU-Alert-for-Breeders-Buyers-Owners-2024.pdf Date Accessed: 4/8/2025.

- Golden Retriever Club of America, Health & Research, How to Participate in Pigmentary Uveitis Research. https://grca.org/about-the-breed/health-research/how-to-participate-in-pigmentary-uveitis-research/ Date Accessed: 4/8/2025

- Canine Health Information Center (CHIC) DNA Repository. https://ofa.org/about/dna-repository/ Date Accessed: 4/8/2025.