-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Jennifer Michaels, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)

By Jennifer Michaels, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)

angell.org/neurology

neurology@angell.org

617-541-5140

Steroid responsive meningitis-arteritis (SRMA) is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease primarily affecting the leptomeninges and associated arteries. Although there are a variety of synonyms (polyarteritis, beagle pain syndrome, aseptic suppurative meningitis, etc.), SRMA is the established and most widely used nomenclature which also most accurately represents the pathologic and clinical features of the disease. Although there are two forms of the disease, this article will focus on the acute form of SRMA as it is the most common. Important clinical, pathologic, and prognostic distinctions regarding the chronic form of SRMA are presented at the end of the article.

SRMA is most commonly seen in dogs between the ages of 6-18 months, although the reported age range is anywhere from 12 weeks to 6+ years. While any breed can be affected, including mixed breed dogs, the most commonly affected breeds include Boxers, Beagles, Bernese Mountain Dogs, and Weimaraners.

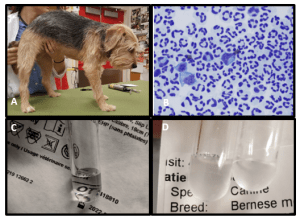

Acute SRMA is characterized by profound cervical pain with guarding of the neck and hunched posture (Figure 1-A), stiff gait, lethargy, inappetance, and fever. Interestingly, the neurologic examination is most often normal except for signs of pain. Although SRMA primarily results in meningitis, it can occur concurrently with immune-mediated polyarthritis resulting in clinical findings of joint pain and effusion.

Clinicopathologic findings may include an inflammatory leukogram characterized by a potentially marked neutrophilia +/- left shift, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperglobulinemia. Diagnosis is typically confirmed with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. CSF can be grossly abnormal with cloudiness secondary to markedly elevated nucleated cell count and/or protein (Figure 1-C & D) or a pink or red discoloration or xanthochromia (yellow discoloration) secondary to acute or chronic hemorrhage. CSF cytology shows a characteristic neutrophilic pleocytosis with a neutrophil percentage often over 80%. The neutrophils are typically non-degenerate (Figure 1-B). The pleocytosis is often marked, often in the several hundred to thousands of nucleated cells/microliter (normal < 5 cells/microliter).

Although MRI can be useful for ruling out other conditions that can appear clinically similar such as other immune mediated diseases like granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis (GME) or bacterial meningitis, we (the Angell Neurology service) oftentimes do not recommend MRI. So often, SRMA cases present with “classic” signalment, clinical signs, and clinicopathologic (including CSF) abnormalities. In most SRMA patients, MRI is normal or only mildly abnormal with mild meningeal contrast enhancement. For this reason, with a consistent clinical picture, typically a CSF tap without concurrent MRI is performed.

More recently, measurement of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum and CSF IgA levels have been used to aid in the diagnosis of SRMA. Assessment of these inflammatory markers can be useful in distinguishing SRMA from other diseases that can cause similar clinical signs (such as GME or bacterial meningitis). Serum CRP in particular can also be useful in monitoring for treatment efficacy and relapse. This is of particular benefit for SRMA patients where, historically, repeat CSF analysis was required for monitoring.

Figure 1. A) A dog with the characteristic appearance of severe neck pain typical of SRMA including low head carriage and kyphosis. B) Typical CSF cytology findings with acute SRMA including high cell density with > 80% non-degenerate neutrophils. C) Normal CSF. Note the water-like appearance and the ability to read text through the sample. D) CSF collected from a juvenile Bernese mountain dog with SRMA. Note the cloudy appearance causing obscuring of text in the background. Turbidity is a common gross finding in CSF with very high nucleated cell count or protein level such as those seen with SRMA.

Treatment for SRMA revolves primarily around immunosuppressive steroids, typically prednisone or prednisolone, at a starting dose of 4 mg/kg/day. As treatment is typically initiated in hospital, dexamethasone sodium phosphate is often administered intravenously for the first several days of treatment at a dose of 0.4 mg/kg/day, although this is not necessary in more mildly affected patients that can be managed on an outpatient bases. After 2-3 days (or once clinical signs have improved), the dose is decreased to 0.2 mg/kg/day of dexamethasone (or 2 mg/kg/day prednisone equivalent). Most dogs will show dramatic improvement in clinical signs within 1 – 3 days. Corticosteroid treatment is then continued for a minimum of 6 months (more commonly up to 9-12 months) with a gradual tapering of the dosage every 6-8 weeks. Regular recheck examinations every 4-8 weeks along with regular CBC and chemistry panel monitoring is recommend to ensure that patients are tolerating long-term steroid therapy as well as to allow for identification of early signs of relapse. SRMA is one of the few immune-mediated neurologic diseases that is often treated with steroids alone. Many neurologists will add a secondary immunomodulatory medications (such as mycophenolate, leflunomide, or cytarabine arabinoside) only in cases of refractory disease or relapse. However, some neurologists prefer to initiate combination therapy at the onset of treatment. Currently, there is no evidence to support one approach over the other.

Early diagnosis and treatment of SRMA is critical for successful long-term management. Overall, the prognosis for SRMA is fair to good. A majority of dogs (80-100%) respond to initial treatment with immunosuppressive corticosteroids. While the initial response rate is excellent, 20-32% of dogs will suffer at least 1 relapse during their lifetime. Typically, this occurs following cessation of corticosteroid therapy with clinical signs recurring a median of 8-28 days following discontinuation of treatment. There are reports of dogs relapsing up to 1.5 – 2 years after discontinuation of treatment. Although less common, up to 10-15% of dogs will suffer a relapse while still on corticosteroid therapy. Fortunately, a large proportion of dogs that suffer a relapse will positively respond to re-initiation of steroid therapy +/- addition of a secondary immunomodulatory medication. Dogs that suffer a relapse may be successfully weaned off of treatment after long-term therapy; however, many will require some degree of life-long therapy to control their disease.

Several studies have been performed looking at possible triggers including demographic, social, environmental, and medical factors. Breed was the only significant predisposing factor (see breeds listed above). Other factors including time of year, geography, sex, neuter status, infectious diseases, and concurrent diseases were not significantly correlated with development or risk of SRMA. Of particular importance, one study specifically evaluated risk associated with vaccination and identified no correlation between type or timing of vaccination and risk of developing SRMA.

As mentioned above, there are two forms of SRMA. This article has focused on the more common acute form. Chronic SRMA, the second form, typically develops as a result of prolonged time to diagnosis, inadequate treatment, or following relapse of acute disease. Clinically, patients with chronic SRMA often present with neurologic deficits such as paresis, ataxia, and/or cranial nerve deficits in addition to cervical pain. Clinicopathologic findings are similar to the acute form with the exception of CSF analysis findings. Changes in nucleated cell count with chronic SRMA are typically less dramatic with only mild – moderate increases. In addition, cytologic abnormalities consist of predominantly mononuclear or mixed cell populations consistent with more chronic inflammation. MRI is more commonly recommended for dogs with chronic SRMA as the clinical signs and clinicopathologic findings are less pathognomonic and more closely mimic those of other CNS diseases, particularly other immune-mediated diseases such as GME. Treatment of chronic SRMA is still rooted in long-term, immunosuppressive corticosteroid therapy; however, the addition of secondary immunomodulatory therapy is almost universally recommended. Based on my personal experience, prognosis with chronic SRMA is less favorable with a higher rate of refractory disease, relapse during treatment, and treatment failure, although this has not been documented in the literature.

In summary, SRMA is a relatively common immune-mediated disease primarily affecting the meninges with resulting, marked cervical pain, lethargy, and fever +/- other clinical abnormalities. Patient signalment and clinical and clinicopathologic abnormalities are often classic, especially in the acute form of SRMA, allowing for a relatively straight forward diagnosis. Treatment centers on long-term immunosuppressive corticosteroid therapy with an overall good prognosis with appropriate treatment. Early identification of clinical signs consistent with SRMA with prompt referral or consultation with a neurologist is critical for maximizing treatment efficacy and overall prognosis. Failure of adequate, early treatment can result in the development of the chronic form of SRMA which is more difficult to diagnose and, in my opinion, to treat.

References:

Bathen-Noethen A, Carlson R, Menzel D, et al. Concentrations of acute-phase proteins in dogs with steroid responsive meningitis-arteritis. J Vet Intern Med. (2008). 22: 1149-1156.

Biedermann E, Tipold A, Flegel T. Relapses in dogs with steroid-responsive meningitis-arteritis. J Sm Anim Pract. (2016). 57: 91-95.

Lowrie M, Penderis J, McLaughlin M, et al. Steroid responsive meningitis-arteritis: a prospective study of potential disease markers, prednisolone treatment, and long-term outcome in 20 dogs (2006-2008). J Vet Intern Med. (2009). 23: 862-870.

Rose JH, Kwiatkowska M, Henderson ER, et al. The impact of demographic, social, and environmental factors on the development of steroid-responsive meningitis-arteritis (SRMA) in the United Kingdom. J Vet Intern Med. (2014). 28: 1199-1202.

Tipold A, Schatzberg SJ. An update on steroid responsive meningitis-arteritis. J Sm Anim Pract. (2010). 51: 150-154.