-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Sue Casale, DVM, DACVS

By Sue Casale, DVM, DACVS

angell.org/surgery

surgery@angell.org

617-541-5048

Chylothorax, the accumulation of chylous fluid in the thoracic cavity, is a rare disorder that is seen in both dogs and cats. In most cases there is no underlying etiology and it is considered idiopathic. Other causes of chylothorax have been reported including right sided heart failure, heartworm disease, vena caval obstruction, lung lobe torsion, and neoplasia.1 Afghan Hounds, Shiba Inus and oriental breeds of cats are predisposed to developing chylothorax.1,2

The lymphatic system is a network of permeable capillaries which allows extravascular protein, tissue fluid and foreign particles to be returned to the circulatory system via ducts that empty into the jugular or precaval vein. The pelvic limbs, via the lumbar lymph trunks, and abdominal viscera, via the intestinal trunk, drain into the cisterna chyli. The cisterna chyli is an elongated sac that runs from the 4th to the 1st lumbar vertebrae, dorsal to the aorta.3 The cisterna chyli narrows cranially at the diaphragm and continues into the thorax as the thoracic duct. In dogs, the thoracic duct courses on the right side, dorsal to the aorta before crossing over to the left side around the fifth thoracic vertebra and terminates at the left jugular vein and cranial vena cava, although there is some variation to its termination.3 The thoracic duct is not always a single structure as multiple collaterals may be present in both the caudal and mid thorax.3 During digestion, triglycerides are transported through this lymphatic system within chylomicrons to be released into the venous circulation. When disruption of lymphatic drainage occurs, there can be an accumulation of chyle in the thoracic cavity resulting in a chylothorax. Altered pressure within the lymphatic system is thought to allow transmural leakage of chyle.4,5 Although traumatic disruption to the thoracic duct can cause chylothorax, when the thoracic duct is experimentally lacerated or transected, the resulting chylothorax has been shown to resolve in 5 to 10 days.6 Experimental obstruction of the thoracic duct rarely results in chylothorax while ligation of the cranial vena cava causes chylothorax in more than half of the dogs.7

Chyle is milky fluid that has a triglyceride level that is higher than serum, often 10 to 100x greater, and a cholesterol level that is less than serum.8 It is a modified transudate that contains mostly small and large lymphocytes. Upon standing, chyle retains its milky appearance although it may have a milky top layer.8 If the patient is anorexic, the fluid will not be as milky or may appear serosanguinous.9 Accumulation of chyle within the thorax can have devastating results. Patients often present with dyspnea and radiographs reveal pleural effusion and thoracocentesis reveals chyle.

Medical management with repeated thoracocentesis is the initial treatment for chylothorax but is not a long term solution. Fibrin development can result in restrictive pleuritis and adhesions and the effusion often becomes pocketed and harder to fully drain.9, 10, 11 The lungs become less tolerant of accidental laceration and pneumothorax can result. Drainage of this fluid can lead to malnutrition because of the loss of lipid and protein. Hypoproteinemia can result as well as dehydration and electrolyte imbalance including fat soluble vitamins such as vitamin K.9,12 Initial conservative therapy for 10 days is reasonable to see if the fluid diminishes or resolves. If the patient requires infrequent (every few months) thoracocentesis, and there does not appear to be a large amount of restrictive disease, conservative therapy can be continued. Low fat diets can decrease the triglyceride content of the chyle but will not decrease the volume.10 Rutin, a benzopyrone, has been recommended, but the reported benefit is slight.13 If frequent taps are required with no decrease in the amount of fluid produced, surgery should be recommended.

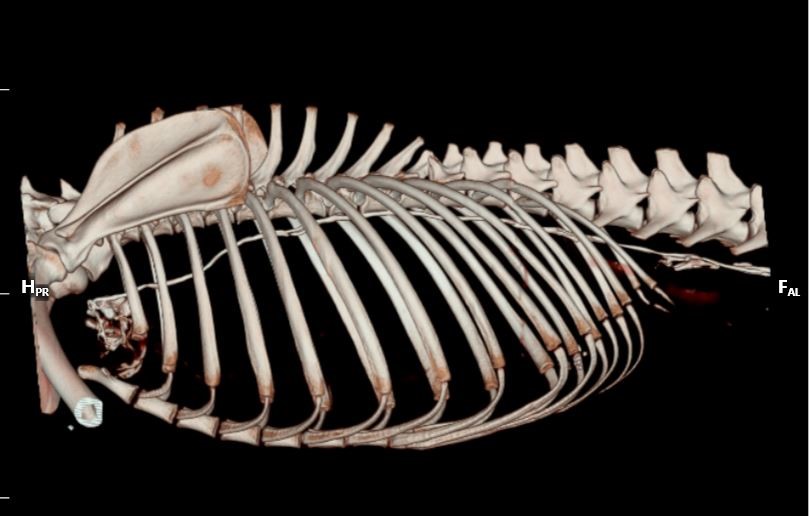

Surgery for chylothorax is not always successful but gives the best chance to resolve the effusion. Multiple procedures have been described for chylothorax including omentalization and pleuroperitoneal shunts, but the most commonly performed and most successful treatment is thoracic duct ligation (TDL) which is often combined with a subtotal pericardectomy and cisterna chyli ablation (CCA).14-19 Prior to surgery, a CT lymphangiogram is helpful to look for branches of the thoracic duct.20 This can be achieved by injecting iohexol into a popliteal lymph node. Contrast will appear in the thoracic duct within 2 to 13 minutes.20 The thoracic duct is seen as it runs along the dorsal surface of the aorta and branches can be identified and surgery can be planned.

Lymphangiogram showing the thoracic duct running just below the spine and leaking in the cranial thorax.

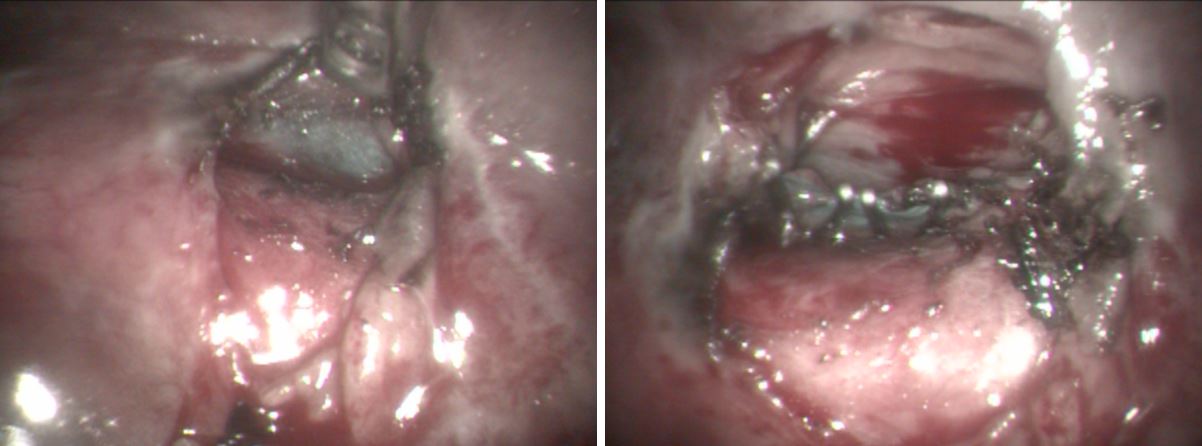

At surgery the thoracic duct and its branches may be difficult to identify as it is typically clear. Feeding cream prior to surgery increases the fat content of the chyle and will make the thoracic duct appear white which can help in identification. Injection of the popliteal or mesenteric lymph nodes at surgery with a small volume of methylene blue will highlight the thoracic duct within 10 minutes making identification simpler when compared to surrounding structures.21 The blue color will persist for up to 60 minutes. Methylene blue can be diluted prior to injection. Traditional surgery involves ligating the thoracic duct through a lateral thoracotomy at the 10th intercostal space. The duct can be ligated en bloc with suture, with surgical clips or with devices like the ultrasonically activated shears or Ligasure™.22, 23 More recently, thoracoscopic TDL has gained popularity.24, 25 Thoracoscopic TDL is achieved with the patient in sternal recumbency and three ports are placed in the caudal thorax for the camera and instruments.24 Dissection dorsal to the aorta reveals the thoracic duct which is ligated with endoscopic clips or a sealing device. Pericardectomy can also be performed with minimally invasive techniques.17,25

Intra-operative injection of a mesenteric LN with methylene blue will highlight the TD and branches can be seen. The picture on the left shows the thoracic duct above the aorta. The second pictures shows multiple surgical clips occluding the thoracic duct.

Postoperative care of dogs with chylothorax is similar to other thoracic procedures. A chest tube is left in place for 24 to 48 hours and fluid production monitored. After that, the chest tube is removed and the patient discharged on a low fat diet. Recheck thoracic radiographs are taken one to two weeks after surgery to assess for recurrence of pleural effusion. If no effusion is present, the patient is monitored regularly for recurrence. If there is continued effusion, treatment with anti-inflammatory doses of steroids and placement of a pleural port can be considered.27,28

TD ligation was reported to have about a 50% success rate in dogs.1,9,11,26 The combination of thoracic duct ligation and pericardectomy have a reported success rate of 60-85% in dogs.2,5,14,17-19 In addition to the TD ligation and pericardectomy, CCA is often performed. CCA allows drainage of lymphatic fluid into the abdomen and prevents pressure build up in the thoracic duct after ligation which may lead to collateral ducts being formed or opened.29 TDL and CCA has shown similar success to TDL and pericardectomy with 83% of dogs having resolution of their chylothorax.2 Currently at Angell Animal Medical Center, we perform TDL, CCA, and pericardectomy for dogs with chylothorax. Success rate with all three procedures performed simultaneously has not yet been reported in dogs. Although chylothorax is a devastating condition, improvement in surgical techniques and the use of minimally invasive surgery has resulted in less morbidity and a better success rate in dogs.

References:

- Fossum TW, Birchard SJ, Jacobs RM. Chylothorax in 34 dogs. JAVMA 1986, 188:1315-1317.

- McAnulty JF. Prospective comparison of cisterna chyli ablation to pericardectomy for treatment of spontaneously occurring idiopathic chylothorax in the dog. Vet Surg 2011, 40: 926-934.

- Evans HE. Miller’s anatomy of the dog. 4th edn. Elsevier, St Louis, 2013.

- Birchard SJ, Cantwell HD, Bright RM. Lymphangiography and ligation of the canine thoracic duct: a study in normal dogs and three dogs with chylothorax. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1982, 18:769-777.

- Fossum TW, Mertens MM, Miller MW, et al. Thoracic duct ligation and pericardectomy for treatment of idiopathic chylothorax. J Vet Intern Med 2004, 18:307-310.

- Hodges CC, Fossum TW, Evering W. Evaluation of thoracic duct healing after experimental laceration and transection. Vet Surg 1993, 22(6):431-435.

- Fossum TW, Birchard SJ. Lymphangiographic evaluation of experimentally induced chylothorax after ligation of the cranial vena cava in Am J Vet Res. 1986, 47(4):967-71.

- Monnet E. Management of chylothorax: is there any hope? WSSAVA 2015 congress.

- Birchard SJ, McLoughlin MA, Smeak DD. Chylothorax in the dog and cat: a review. Lymphology 1995, 28:64-72.

- Sikkema DA, McLoughlin MA, Birchart SJ, et al. Effect of dietary fat on thoracic duct lymph volume and composition in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 1993, 7:119.

- Birchard SJ, Smeak DD, Mcloughlin MA. Treatment of idiopathic chylothorax in dogs and cats. JAVMA 1998, 212:652-657.

- Willard MD, Fossum TW, Torrance A, Lippert A. Hyponatremia and hyperkalemia associated with idiopathic or experimentally induced chylothorax in four dogs. JAVMA 1991, 199:353-358.

- Thompson MS,Cohn LA, Jordan RC. Use of rutin for medical management of idiopathic chylothorax in four cats. JAVMA 1999, 215(3):345-8, 339.

- Adrega da Sulva C, Monnet E. Long-term outcome of dogs treated surgically for idiopathic chylothorax: 11 cases (1995-2009). JAVMA, 2011; 239(1): 107-113.

- Williams JA, Niles JD. Use of omentum as a physiologic drain for treatment of chylothorax in a dog. Vet Surg 1999, 28 61-65.

- Smeak DD, Birchard SJ, McLoughlin MA et al. Treatment of chronic pleural effusion with pleuroperitoneal shunts in dogs: 14 cases (1985-1999). JAVMA 2001, 219 (11): 1590-1597.

- Allman DA, Radlinsky MG, Ralph AG, Rawlings CA. Thoracoscopic thoracic duct ligation and thoracoscopic pericardectomy for treatment of chylothorax in dogs. Vet Surg 2010, 39:21-27.

- Hayashi K, Sicard G, Gellasch K, et al. Cisterna chyli ablation with thoracic duct ligation for chylothorax: results in eight dogs. Vet Surg 2005, 34:519- 523.

- Stockdale SL, Gazzola KM, Strouse JB, et al. Comparison of thoracic duct ligation plus subphrenic pericardiectomy with our without cisterna chyli ablation for treatment of idiopathic chylothorax in cats. JAVMA, 2018, 252:976-981.

- Naganobu K, Ohigashi Y, Akiyoshi T, e al. Lymphography of the thoracic duct by percutaneous injection of iohexol into the popliteal lymph node of dogs: experimental study and clinical application. Vet Surg, 2006, 35:377-381.

- Enwiller TM, Radlinsky MG, Mason DE, et al. Popliteal and mesenteric lymph node injection with methylene blue for coloration of the thoracic duct in dogs. Vet Surg 2003, 32:359-364.

- MacDonald NJ, Noble PJM, Burrow RD. Efficacy of en bloc ligation of the thoracic duct: descriptive study in 14 dogs. Vet Surg 2008, 37:696-701.

- Leasure CS, Ellison GW, Roberts JF, et al. Occlusion of the thoracic duct using ultrasonically activated shears in six dogs. Vet Surg 2011, 40:802-804.

- Radlinsky MG, Mason DE, Biller DS, Olsen D. Thoracoscopic visualization and ligation of the thoracic duct in dogs. Vet Surg 2002, 31:138-146.

- Mayhew PD, Culp WTN, Mayhew KN, Morgan ODE. Minimally invasive treatment of idiopathic chylothorax in dogs by thoracoscopic thoracic duct ligation and subphrenic pericardectomy: 6 cases (2007-2010). JAVMA 2012, 241(7):904-909.

- Birchard SJ, Smeak DD, Fossum, TW. Results of thoracic duct ligation in dogs with chylothorax. JAVMA 1988, 193:68-71.

- Sicard GK, Waller KR, Mcanulty JF. The effect of cisterna chyli ablation combined with thoracic duct ligation on abdominal lymphatic drainage. Vet Surg 2005, 34:64-70.

- Cahalane AK, Flanders JA, Steffey MA, Rassnick KM. Use of vascular access ports with intrathoracic drains for treatment of pleural effusion in three dogs. JAVMA 2007, 230(4): 527-531.

- Brooks AC, Hardie RJ. Use of the pleuralport device for management of pleural effusion in six dogs and four cats. Vet Surg 2011, 40:935-941.