-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Naomi Ford, DVM, DACVR

By Naomi Ford, DVM, DACVR

angell.org/diagnosticimaging

617-541-5139

Radiographs of the thorax to evaluate the pulmonary parenchyma are one of the most common diagnostics performed. They are used as a screening tool in a patient that “seems a bit off,” they are used for complete staging if a cancerous or infectious diagnosis has been made, and of course they are the first and often quickest assessment we rely on for trying to identify what is wrong in that very stressful situation when a patient is dyspneic, and our main goal is to determine how to provide them with relief.

Despite their ubiquitous use, their interpretation can seem daunting and challenging. So many factors go into their interpretation and sometimes they can only serve as the starting point for diagnosis rather than the end point, because we are limited by the ways in which the body manifests such a wide variety of diseases. In radiographic studies, technique ‑ including positioning, exposure, timing, and consideration of potential artifacts, is very important. I would argue, however, that these are of the utmost importance when attempting to evaluate the pulmonary parenchyma because we are often attempting to either identify focal small changes, or trying to distinguish fine details to help us choose what pattern is present, amongst the already complex structure of the lung itself.

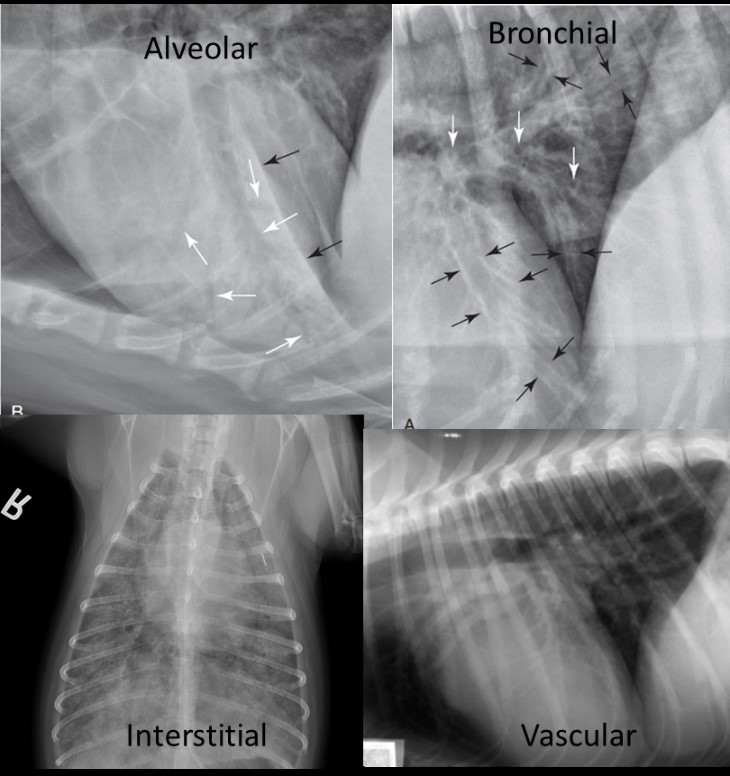

The paradigm for interpretation has long been established as one of patterns; as it helps us attempt to localize the problem in an anatomic/pathologic sense, and thus form a list of differential diagnoses that can then be ranked by combining the radiographic findings with the other pertinent facts of the clinical work up (history, signalment, bloodwork etc.). Those main patterns are:

- Alveolar pattern: Characterized by the lobar sign, air bronchograms and border effacement. The most common causes of this pattern are pneumonia, atelectasis, dense edema, or more rarely hemorrhage or some manifestations of neoplasia.

- Bronchial pattern: Characterized by “donuts and tram-tracks,” indicating that the disease is within/affecting the bronchial walls, such as with infectious or inflammatory bronchitis. Sometimes edema can also appear this way with “peri-bronchial cuffing.”

- Interstitial pattern: Further broken down into the “structured” category of nodules and masses (solid or cavitated) that arise in the interstitium, or the “unstructured” category of a more infiltrative process (neoplasia, infection, fibrosis).

- Vascular pattern: This is a bit more straightforward and seen with systemic to pulmonary shunting (i.e. PDA), fluid overload (possibly with edema) and heartworm disease.

Of course because this is medicine and life, combinations of these patterns are often seen, with numerous patterns distributed throughout various regions, and thus we must try to identify the predominant pattern and explain these combinations to guide the next diagnostic test or move forward based on the most likely diagnosis. List and tables of the differential diagnoses typically seen with each pattern can be found in numerous sources (see references below). Those next steps may be further imaging, usually a CT scan if necessary for better characterization of the lesion or for surgical planning; obtaining a sample, most commonly either through bronchoalveolar lavage or ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration; or initiating treatment and rechecking radiographs as indicated to confirm that the suspected diagnosis is resolving.

Reference

- Thrall, Donald et al. Textbook of Veterinary Radiology 6th Saunders, 2013.

- Larsen, M.M. Radiographic evaluation of pulmonary patterns and diseases (Proceedings). Apr 01, 2008.

- Schwartz et al. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Thoracic Thoracic Imaging.