-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

From Splints to Pacemakers:

How Angell Led the Astounding Evolution of Veterinary Medicine

By Bella English

Boston Globe Magazine, 2015

At Angell Animal Medical Center over a few days recently, the staff was busy, as always, with various cases.

Dr. Allen Sisson, a veterinary neurologist, was operating on a beagle with severe neck pain. Dr. Nancy Laste, an animal cardiologist, had opened the constricted heart valve of a Catahoula hound named Guinness. In the Emergency and Critical Care Unit, Dr. Virginia Sinnott was working two cat cases, including one that had been rushed to the hospital in the midst of a seizure. Sinnott and her team performed a phlebotomy to remove excess red blood cells and, with them, the cat’s seizures. The other cat was near death after being hit by a car. The emergency team used CPR to jump-start her heart. Still, she died – but not before her grieving owners could say goodbye. In the Pain Medicine Service, Dr. Lisa Moses was doing acupuncture on a 15-year-old arthritic cat named Betsey who has difficulty walking.

Exploring the history of Angell, the country’s second oldest veterinary hospital, which turned 100 on March 1, is like walking through the history of veterinary medicine, from the early days of rudimentary splints to today’s sophisticated heart pacemakers. The evolution, no surprisingly, coincides with the changing emotional place that animals hold in our lives. When Angell was founded, animals were considered little more than utilitarian beasts of burden that transported people and goods. Today? They are family members who share our couches, our vacations, even our beds. We are as likely to post on Facebook videos and pictures of our dogs playing in a sprinkler as we are of our children.

A century ago, Angell Memorial Animal Hospital, as it was known until 2003, had dirt floors. Its primary goal was treating horses, oxen, sheep, and other farm animals. There were stalls for sick horses, an equine surgical suite, and even an electric horse ambulance. In 1940, the hospital started the first internship program for graduates of veterinary schools, establishing Angell as an international teaching facility. It remains one of the most prestigious vet residencies in the world.

Today, Angell has 19 specialty services that range from anesthesia to ophthalmology. There are surgeons and pathologists, dentists and dermatologists. There are CTs and MRIs designed especially for animals. There’s acupuncture for pain relief, nausea, loss of appetite, and constipation, among other problems. And the Behavior Services staff provides “positive-based behavior modification treatment plans” for issues such as aggression, anxiety, and furniture scratching.

Today, Angell has 19 specialty services that range from anesthesia to ophthalmology. There are surgeons and pathologists, dentists and dermatologists. There are CTs and MRIs designed especially for animals. There’s acupuncture for pain relief, nausea, loss of appetite, and constipation, among other problems. And the Behavior Services staff provides “positive-based behavior modification treatment plans” for issues such as aggression, anxiety, and furniture scratching.

“The world has changed dramatically in the last 100 years, but in many ways our overall vision and passion in addressing the health and well-being of animals has not changed one bit,” says hospital president Carter Luke. “One of the core principles at the dedication of the hospital was that every creature capable of suffering was entitled to our sympathy.”

That first year, Angell treated 4,382 animals. By 1917, the caseload had grown to 10,813. Last year, the hospital saw 61,595 cases, or almost 170 a day on average, its largest number ever.

Angell’s roots were unusual: an animal hospital operated by a humane society. It’s a relationship that continues to this day and is reflected in its name, MSPCA-Angell. The hospital on South Huntington Avenue in Jamaica Plain shares space with its parent organization, the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, which also runs a rescue shelter on-site.

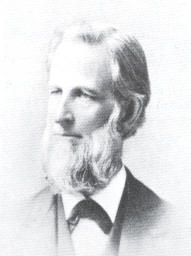

George Thorndike Angell

It all started with George Thorndike Angell, a Boston lawyer who was appalled at the 1868 case of two horses that were ridden so hard over 40 miles of rough roads that they dropped dead in their tracks. Within a month, Angell incorporated the MSPCA, and two months later had helped pass the state’s first anti-cruelty laws. The same year the organization produced “Our Dumb Animals”, the first periodical in the country dedicated to animal welfare. Today it’s a newsletter called “Companion” that features humane and veterinary news from around the region and world.

“George Angell was active the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad,” says Luke. “It was a natural for him to adjust his thinking about empathy and sympathy and care and well-being to include animals. He was a good role model for us, even going back 147years.”

A veterinarian and Baptist minister named Dr. Francis H. Rowley succeeded Angell as MSPCA president in 1910. He obtained the first animal ambulance and sought funding for and helped open the hospital, then on Longwood Avenue.

Dr. Robert Leighton is 98 years old, a retired Angell veterinarian whose memories of the early days of veterinary medicine remain sharp and vivid. “I graduated from Roxbury Latin in 1936 and there was absolutely no work,” he says. “My father told me to go work for nothing.” Leighton, who now lives in California, went to the University of Pennsylvania for undergraduate and veterinary school, volunteering summers at Angell, where he later joined the staff. In the 1930’s, he says, Dr. Irwin F. Schroeder treated a St. Bernard with a broken leg. Orthopedic surgery was still based on horse practice. But Schroeder’s technician made a splint out of a gas pipe, its ring padded with cotton and covered with tape. Later, the splints were made of aluminum rods, to restrict the joint while the leg bones healed.

“At the time, it was an advance over the usual fracture treatments and got to be widely used,” Leighton says. “The only alternative was to amputate the limb.”

In the 1930s, the use of pentobarbital sodium for anesthesia made surgery much safer. It replaced Nembutal – which has been used in the United States for executions – for dog surgery and ether for cats.

In the 1930s, the use of pentobarbital sodium for anesthesia made surgery much safer. It replaced Nembutal – which has been used in the United States for executions – for dog surgery and ether for cats.

In 1934, the hospital performed the first hernia repair in a dog. Dr. Lawrence Blakely, a pioneer in soft tissue surgery, used a bicycle pump to respirate his patient. “The dog was under Nembutal,” says Leighton. “A rubber tube was inserted into the trachea and blocked off with a moist sponge. A hole in the hose to the tube was occluded with a finger with the pump was pushed down. The finger was released when the pump was pulled up.”

In 1939, protocol changed – by way of a surgeon at a human hospital, the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. “Veterinary medicine was far behind human medicine in this aspect,” Leighton remembers. “We were using sterile drapes and gloves, but caps, masks, and gowns came a bit later, I found that I was ordering older surgeons to re-glove, since they had adjusted their glasses with their gloved hands.”

The use of new antibiotics, the “sulfas” that were the precursors of penicillin, also helped in the fight against infection. As the mid-20th century came and went, other veterinary advancements became commonplace. In 1945, Angell was the first veterinary hospital to admit sick animals for overnight care. In 1950, its cardiologists were among the first in the world to implant a pacemaker into a dog. In 1959, Angell added an intensive care unit. In 1976, it moved from Longwood Avenue to Jamaica Plain, nearly doubling its space to 92,000 square feet. In 1997, the first successful feline kidney transplant was conducted at Angell.

Today it has 51 doctors on staff, 30 medical interns and residents, and 237 other support personnel such as technicians and nurses.

Lisa Moses, who did her internship and residency at Angell, is now head of its Pain Medicine Service. In her 23 years at Angell, this vet has seen everything from a homeless person’s dog hit by a car to Middle Eastern royalty who jetted their pregnant dog for prenatal care and delivery.

“I’ve had people bring me tarantulas,” Moses says. “Someone’s always stepping on them.”

How exactly do you examine a tarantula? “In a zip-lock bag.”

Moses loves the variety of cases. “Yesterday, there was a rooster with a broken leg in the emergency room, a beautiful rooster. I love that I walked in through the Radiology Department and there were two scarlet macaws,” she says.

Moses loves the variety of cases. “Yesterday, there was a rooster with a broken leg in the emergency room, a beautiful rooster. I love that I walked in through the Radiology Department and there were two scarlet macaws,” she says.

In 2005, Moses started the Pain Management Service. “We are devoted to diagnosing difficult-to-diagnose pain, such as nerve pain, and difficult-to-manage pain.” Her patients typically have multiple ailments, most are near the end of their loves, and her team uses as combination of drugs and non-drug therapies. She says she gets many of her ideas from Boston Children’s Hospital. “I hang out there when I can, because there really isn’t a model for this in veterinary medicine,” Moses says.

The biggest obstacle to treating pain in her patients, of course, is that they can’t tell her where it hurts. “A lot of it has to do with behavioral changes,” she says, “a dog who stops lifting his leg to urinate or cats who stop licking when they groom.”

On a sabbatical, Moses took a course at Colorado State University on veterinary medical acupuncture. Yes, acupuncture for pets. “I do it in patients who do not tolerate drugs well or need something to stay on top of the drugs,” she says. Besides cats and dogs, she’d done acupuncture on birds and farm animals. Her bookshelf includes How to Massage Your Cat and Doga (dog yoga).

Perhaps the biggest change she has seen is not in how the animals are treated but in their relationship with their owners. “Animals live so much longer now, and when you have a relationship with a dog who sleeps in your bed for 17 years, it’s not the same relationship with a dog who slept in the garage,” Moses says. Yes, her old dog slept in the bed; now her cats do.

Parts of this she attributes to cultural changes, with the delay of marriage and kids, more people are living alone, and having less face time with others. “It’s the perfect setup to put animals into that mix, into that hole in our lives that we created,” she says. “Especially in a place like Boston that’s urban, dense, and where people come to from other places.”

Allen Sisson, the neurologist, does both spine and brain surgery on animals every week. One of his dog patients has had brain surgery three times for tumors, at a cost of about $5,000, including CT and MRI scans, anesthesia, surgery, and hospitalization.

“It used to be if you told people you were doing a CT scan on a dog they thought it was ludicrous,” says Sisson, who arrived at Angell in 1978. “No one today thinks it’s odd.”

Sisson is hopeful for medical breakthroughs on neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and ALS for humans – and animals. “There is canine cognitive dysfunction like dog Alzheimer’s and degenerative myelopathy, which is like ALS,” he says. “If they can figure out how to treat people, we can immediately learn how to treat dogs, too.”

Article posted with permission from PARS International Corp.