-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Rob Daniel, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)

By Rob Daniel, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)![]()

angell.org/neurology

neurology@angell.org

617-541-5140

April 2021

Acute, severe thoracolumbar spinal cord injuries make up 4% of cases presenting to ER facilities across North America, with ~75% due to some form of intervertebral disc (IV) displacement. Recent reports describe >20,000 surgeries annually.

Acute, severe thoracolumbar spinal cord injuries make up 4% of cases presenting to ER facilities across North America, with ~75% due to some form of intervertebral disc (IV) displacement. Recent reports describe >20,000 surgeries annually.

During embryologic development, the intervertebral disc arises from differing regions, with the annulus fibrosus (AF) arising from sclerotome, and the nucleus pulposus (NP) originating from notochord. Notochordal cells persist into adulthood in chrondrodystrophic (CD) breeds, whereas the notochordal cells disappear before 2 years of age in nonchondrodystrophic breeds (NCD).

The AF is collagen-rich tissue, with the NP rich in proteoglycans and a transitional zone (TZ) between the two. Regions of disc that contact the adjacent vertebral bodies are hyaline-like cartilaginous tissue. Relatively inelastic Type I and II collagen fibers are contained within the intervertebral disc in organized, consistent patterns, with Type I predominantly in AF and Type II within NP. Elastin is present within the IV disc. Think in terms of a pillow for the IV disc, a viscoelastic cushion countering compressive forces, with load being transferred from NP to AF. The NP is 80% water.

Sensory nerves are sparse in the dorsal AF, with the dorsal longitudinal ligament innervated profusely and innervation to the outer AF communicating with 2 spinal levels cranial and caudal to the particular intervertebral (IV) disc.

In chondrodystrophic dogs, the NP loses its prior ability to retain water. This leads to more load to AF and an increase in AF size. As a result, weaker and stiffer inherent properties lead to structural failure, with AF defects, tears and uneven displacement of load.

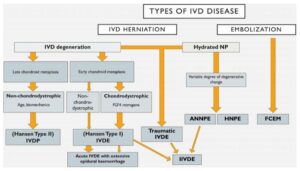

The Nomenclature of Hansen’s Type I (extrusion, chondroid metaplasia) and Hansen’s Type II (protrusion, fibroid metaplasia) intervertebral disc disease is pervasive and has upheld since this system of classification was proposed in a landmark, mid-twentieth century paper, although both situations are not mutually exclusive of one another.

In order to become better at care delivery, it is helpful to have agreed-upon nomenclature that is pervasive and well-adopted, to reduce heterogeneity in description, facilitate communication and improve data quality.

Intervertebral disc degeneration is defined as the structural failure of the IV disc associated with abnormal or accelerated changes in aging. IV disc herniation defined as abnormal, localized displacement of the IV disc beyond bounds of IV space. IV disc extrusion describes a complete rent in AF, with displacement of NP from prior containment. IV disc protrusion describes rupture of inner layers of AF, with partial displacement of NP and annular hypertrophy. Acute, non-compressive NP extrusions (ANNPE) describe small volume NP displacements resulting in spinal cord injury, which may be traumatic in origin. Velocity, dwell time and impact force are major factors in determining severity of spinal cord injury.

The importance of a thorough history and complete physical examination cannot be overstated. Stress on the pet’s family is difficult to quantify and informed consent can be difficult due to various reasons, including status of pet, anxiety, need for timely decision making and/or financial concerns.

Spinal cord contusion and compressive forces have their earliest and most harmful effects on the myelin sheathing neurons within the spinal cord. Axons that typically conduct deep pain/nociception (DP) are relatively small with minimal to no myelin sheathing. Although the clinician is at an inherent disadvantage of testing deep pain/nociception, compared to people who can describe sensation, excellent interobserver variability exists between examiners of varying backgrounds. Place the dog on the ground and watch first, then assist if needed, followed by testing for deep pain/nociception only if clear, purposeful motor function is not present. The presence or absence of nociception/deep pain is critical in decision making.

The decision to take radiographs is subjective. When discussing examination findings with the family of the pet, consider how likely radiographs will change what the examiner is already recommending.

Advanced imaging, namely and in overwhelming majority in 2021, MRI or CT, are needed for a definitive diagnosis. The decision to refer a neurologic pet suspected for intervertebral disc-related spinal cord injury for evaluation is subjective, but understanding a severity vs. time graph can be helpful.

After evaluation by a veterinary neurologist and review of advanced imaging results, the decision for surgical intervention is overwhelmingly rooted in the purpose of decompression. Surgical approaches are relatively few for the majority of intervertebral disc displacement cases, including hemilaminectomy, ventral slot and dorsal laminectomy. Fenestration is always considered.

The cornerstone of conservative management is rest. Medications can be helpful, keeping in mind the relative risk of the particular medications, along with the risk of making an acutely myelopathic pet feel better in the absence of rest. Corticosteroids, NSAIDs, opioids, muscle relaxants, gabapentin/pregabalin and amantadine are common in medical management. Adjunctive strategies, such as physical therapy, are often considered.

Whether referral for evaluation and surgical intervention or conservative management, follow-up with the family is important in maintaining a strong relationship, rapport and health care of the pet.

References

- Advances in Intervertebral Disc Disease in Dogs and Cats. James M. Fingeroth and William B. Thomas. Wiley Blackwell, 2015

- An Update on hemilaminectomy of the cranial thoracic spine: Review of six Cases. Bray, K.B, Early, P.J., Olby, N.J. and Lewis, M.J.Open Veterinary Journal (2020) Vol 10(1): 1621.

- Fenn, J., Olby, N.J. and Canine Spinal cord Injury Consortium (CANSORT-SCI). Classification of Intervertebral Disc Disease. Frontiers in Veterinary Science October 2020 Volume 7, Article 579025

- Olby, N.J., da Costa, R.C., Levine, J.M., Stein V.M. and the Canine Spinal Cord Injury Consortium CANSORT SCI) Prognostic Factors in Canine Acute Intervertebral Disc Disease. November 2020 Volume 7 Article 596059