-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Michael M. Pavletic DVM, DACVS

Michael M. Pavletic DVM, DACVS

Director of Surgical Services

Angell Animal Medical Center

angell.org/surgery

617-541-5048

There are occasions when the veterinarian unexpectedly faces greater skin tension than anticipated after removal of a skin tumor or the debridement of an open wound. This may be the result of misjudging the regional skin tension or unexpected elastic retraction of the skin margins. In many cases, gaining an additional 1-2 centimeters can make all the difference between primary closure and wound dehiscence. The following are my “go to” options to gain a little additional skin to facilitate closure of those problematic incisional closures.

Properly Positioning the Patient on the Surgery Table

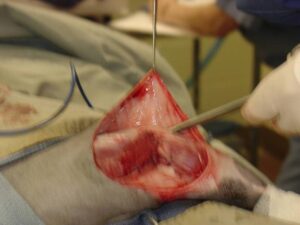

Figure 1: Undermining healthy skin can be safely performed if care is taken to preserve regional circulation during this procedure.

Stirrups used to secure the extremities to the surgery table can impair closure of surgical wounds involving the lower thoracic and caudal abdominal skin. With the patient in dorsal recumbency, abduction of the secured limbs can place variable degrees of tension in these areas. Tension can be reduced in the patient simply by loosening the stirrups. In large dogs, the skin of the trunk can be trapped against the table surface due to the weight of the patient. Rolled up towels or sandbags can be slipped beneath the patient’s pelvic area and shoulder/cranial sternal area. This simple maneuver can release the skin pinned against the table and facilitate closure of trunk wounds.

Undermining the Skin

Figure 2: Skin hooks (single or double pronged) are a useful means of manipulating the skin to minimize trauma.)

This is often the first option to consider in mobilizing the skin. Undermining below the dermis usually is performed by elevating the skin margin with atraumatic forceps or skin hooks, followed by the insertion/spreading of Metzenbaum scissors. Skin is undermined beneath the panniculus muscle layer (the largest being the cutaneous trunci muscle) where it is present. Care is taken to avoid trauma to the deep dermal surface where the subdermal plexus is located. Direct cutaneous vessels encountered can be preserved by dissecting around them. In fact, considerable undermining can be performed when the direct cutaneous artery and paired vein are protected during this surgical maneuver. Both sides of the incision are undermined. This procedure can significantly reduce skin tension, depending on the body region involved. The skin overlying the trunk is easier to undermine than the skin of the mid- to lower extremities.

Intraoperative Load Cycling

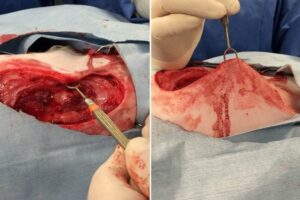

Figures 3A and 3B: Intraoperative view of stretching skin intraoperatively (Load Cycling Technique).

Load cycling refers to a method of stretching skin intraoperatively using skin hooks. The procedure is designed to take advantage of the processes of “mechanical creep” and “stress relaxation:” dermal collagen fibers under tension can slowly stretch parallel to the force applied to the skin, thereby allowing the skin to stretch beyond its natural or inherent elasticity. The author has used this simple technique on a number of occasions to gain 1-2 cm of skin advancement to facilitate wound closure. One or two skin hooks are used to grasp the skin margins: once engaged, moderate traction is applied to stretch the incision. The author stretches the skin for 30-45 seconds; this stretching process is resumed around 30 seconds later for a total of 5-10 minutes per side of the incision. The skin is assessed intraoperatively to determine if sufficient elastic gain has been achieved.

Small Release Incisions

Figure 4: Release incision (bilateral) used to close an elbow ulcer. The resultant defect normally heals within three weeks when used for closing wounds overlying the olecranon.

One or more small release incisions can be easily employed to reduce incisional tension. In many closures, the greatest tension in closure is located at the widest (central) area of the closure. Normally placed 2-3 cm from the incisional border, 1cm full-thickness release (relaxing) incisions are created parallel to the cutaneous border (one side or both sides of the closure area). Two small release incisions can be placed 15-20mm apart, a second row of one or more release incisions can be staggered between the rows (15-20mm from this first line). During initial placement of appositional skin sutures, the comparative ease of closure will help the surgeon assess where to place the release incisions and the number required. A dressing and bandage are normally required to protect the open release incisions until healing is complete.

“Walking” or “Tacking” Sutures

Figure 5A: Resection of the mass from the left side of the tail. Figure 5B: Closure of the skin in a spiral fashion to better distribute incisional tension. Figure 5C: To further reduce circumferential skin tension after closure, mini-release incisions were used on the opposite side of the tail. Following the creation of the incisions, perpendicular to the line of tension, the mini-release incision may close (partially or completely) in the opposite direction.

After undermining the skin, it may be useful to place a few tacking sutures between the exposed dermal surface and the adjacent underlying muscle fascia. The skin can be stretched toward the defect, followed by placement of the sutures. Tacking or walking sutures can reduce elastic retraction of the skin and divert some skin tension from the incision. It may require a few tacking sutures on one or both sides of the closure area. If the skin peripheral to the incision lacks any notable mobility, release incisions are a better option.

Combining Techniques

Figure 6A: Small mast cell tumor adjacent to the left lower eyelid. Figure 6B: Placement of intradermal sutures to prevent offset elastic retraction of the advancing skin. Figure 6C: The lower eyelid function is maintained by neutralizing the elastic rebound of the advanced skin margin.

All four of these procedures can be used alone, or in combination, since they are unlikely to cumulatively compromise circulation to the skin. For example, the skin can be undermined initially, followed by load cycling. If additional laxity is required, the selective use of release incisions can be employed. As an alternative to release incisions, the surgeon may select the use of tacking sutures to maintain the position of the stretched skin to close the skin incision.

For more information about Angell’s Surgery service, please visit angell.org/surgery. Dr. Pavletic can be reached at 617-541-5048, or by e-mailing mpavletic@angell.org or surgery@angell.org.