-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Brooke Simon, DVM

By Brooke Simon, DVM

angell.org/dermatology

dermatology@angell.org

617-524-5733

History of Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy and cryosurgery date back to the 19th century, with local applications of cooling used for pain control and to treat advanced cancers. However the use of cold to treat different injuries and inflammation dates back to ancient Egyptians in 2500 BCE.

The development of vacuum flasks to help facilitate storage of liquefied gases further progressed the process of cryotherapy, eventually leading to liquid carbon dioxide (-78.5℃) being used in the early 1900’s by Lortat-Jacobs and Solente in Paris to treat skin lesions and gynecological lesions. While this proved effective to treat these lesions, the adhesion of the applicator tip to the tissue and difficulty of removal lead to exploration of additional methods. This lead to liquid oxygen (-182.9℃) being developed with good results in treatment of dermatologic conditions, although its highly combustible nature limited its use.

Liquid nitrogen (-196℃) first became available after World War II, when in 1950 Dr. Ray Allington used cotton swabs dipped in liquid nitrogen to treat various types of non-neoplastic skin disease.

The more modern approach of cryosurgery began between the collaboration of a physician, Dr. Irving Cooper, and an engineer, Arnold Lee. Their development of a cryosurgical probe has been the basic model for all subsequent cryosurgical probe models. The more commonly used nitrogen spray device used today was developed by dermatologist Dr. Douglas Torre in 1965, and further modified to a handheld spray device using liquid nitrogen in 1968 by Dr. Setrag Zacarian.

Freezing/Thawing Effects

Freezing of tissue has been extensively researched, with a few hypotheses on how freezing results in cell destruction and death. The primary theory involves direct cellular injury from the extracellular space, as a result of high concentrations of extracellular ice causing cell dehydration. This occurs through two mechanisms: slow cooling rates resulting in freezing in the extracellular space causing the cells to dehydrate themselves through osmosis, and membrane destabilization during the freezing and thawing cycles.

An additional mechanism likely involves intracellular ice formation, causing disruption of the organelles within the cell as well as the membrane of the cell. A second theory involves an immunological response to freezing, with the immune system becoming reactive to destroyed frozen tissue, which then results in the immune system reacting to any remaining residual tissue. The final theory suggests that damage to the blood vessels of the lesion through freezing results in loss of blood flow, leading to tissue damage and death.

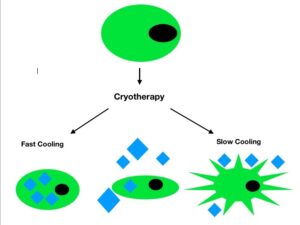

Figure 1: Diagram of the mechanisms of cell injury after freezing. The diamonds represent ice crystals. Fast cooling after freezing creates an osmotic discrepancy between cells and the extracellular space, and they are not able to lose water fast enough to maintain their integrity. This allows for intracellular ice crystals to form, disrupting normal cell function. When the temperature is cooled slowly, ice crystals form along the extracellular space, resulting in shrinkage and dehydration of cells. As the temperature is gradually decreased (central cell in the diagram) ice crystals form in both the intracellular and extracellular space.

Thawing of these lesions has varying effects, but they are determinate on the cooling rate. Slow thawing after cryotherapy is performed allows for the maximum amount of ice to form, thereby causing the greatest effects on the cells. Completely thawing the lesion before re-freezing is essential, as this creates further ice formation and allows for recrystallization of the ice crystals. Recrystallization within cells occurs when smaller crystals thaw, then form larger and larger crystals over time and eventually result in punctures to the cell membrane. Rapid cooling and rapid thawing, however, has also proven to be effective, by creating smaller ice crystals within the cells. This then allows for further recrystallization.

The degree of cellular injury does vary in in-vivo situations: cells in tumor tissue along the skin will have varying levels of freezing effects due to the size of the lesion and vascularity changes. Types of cells involved, exposure to air, or state of malignancy will also affect freezing time and effectiveness. Previous studies have shown cells near the center of the probe experience the lowest temperature and fastest cooling rates, whereas the tissue along the outer edge of the lesion typically has near-normal body temperature.

Cryotherapy at Angell

Within the Dermatology Service at Angell Animal Medical Center, we offer cryotherapy for superficial masses along the skin as a non-anesthesia option of mass removal. While not all superficial masses can be removed via cryotherapy due to location or size, many external masses such as sebaceous adenomas or viral papillomas respond very well to cryotherapy freezing. Any questions regarding referral for cryotherapy can be directed to our Dermatology service at dermatology@angell.org.

References

- Cryosurgery: A review. Yiu, W et al. Int J Angiol. 2007 Spring; 16(1): 1-6

- History of Cryotherapy. Freiman, A et al. Dermatology Online Journal. 2005; 11(2): 9

- The Haemolysis of human red blood-cells by freezing and thawing. Lovelock, JE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1953 Mar; 10(3): 414-23.

- Role of Plasma Membrane in Freezing Injury and Cold Acclimation. Ann Rev Plant Phsiol. 1984; 35: 543-84.