-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Zachary Crouse, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM)

By Zachary Crouse, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM)

angell.org/internalmedicine

617-522-7282

Introduction

Cystotomy has traditionally been the default method for treatment of cystolithiasis in dogs and cats.1,2 As veterinary understanding of cystoliths has advanced, including stone types and risk factors for their development, it is important to evaluate the most appropriate treatment options for our patients on an individual basis. A good rule of thumb when managing cystoliths, is to use the least invasive method possible to achieve a good outcome. The goal of this article is to provide clinicians with a simple and clinically useful approach to managing cystolithiasis.

Is Surgical Intervention Warranted?

The first question that should be addressed when faced with cystolithiasis, is whether or not the patient requires surgical intervention. Urinary outflow obstructions caused by cystolithiasis warrants immediate surgical intervention. In cases where medical management has been attempted, surgical intervention is necessary when there is an increased size or number of stones and when there are clinical signs associated with nondissolvable cystoliths that cannot be removed using minimally invasive techniques.2 When it is determined that a patient requires surgical intervention, laparoscopic assisted cystotomy and percutaneous cystolithotomy procedures should be considered in addition to traditional cystotomy. Laparoscopic assisted cystotomy has been shown to have a similar procedural time with shorter hospitalization time when compared to traditional cystotomy.3 Nonclinical cystoliths that are not causing clinical signs do not require removal.1

Identify cystolith composition when possible

The best way to identify cystolith composition is to submit retrieved stones to the University of Minnesota’s Urolith Center (vetmed.umn.edu/centers-programs/minnesota-urolith-center). In fact, it is now considered standard of practice to submit retrieved uroliths for analysis.4 All retrieved stones should be submitted for analysis, as opposed to a random sampling of the stones, due to the potential for stone variation and the presence of compound stones. Stones may be retrieved by owners after their dog has voided, during appointments by manually agitating the bladder and then having the patient void while the urine is collected, via urohydropropulsion, or via surgical intervention.

Dissolution should be attempted in potentially dissolvable cystoliths

Struvite, urate, and cystine cystoliths all have the potential for dissolution.1 If the cystolith type has not been determined with stone analysis then struvite stones should be considered likely in dogs with moderately radiopaque stones, alkaline urine pH, and the presence of a urinary tract infection caused by urease producing bacteria.1 Struvite stones are likely in cats with moderately radiopaque stones and a neutral urine pH.2 Sterile struvite cystoliths commonly dissolve in 2-5 weeks, and those associated with infection dissolve in 1-4 months.1,2 Information on dissolution diets, medications, and supplements is easily accessible on the University of Minnesota Urolith Center website.

Minimally invasive cystolith removal should be pursued when possible

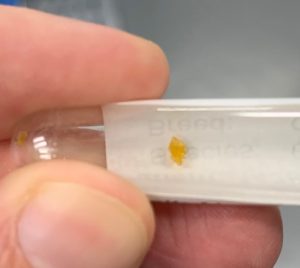

Figure 2: Female dog with struvite cystolithiasis. Even very large stones can be dissolved with appropriate diet and treatment of urinary tract infections.

Urohydropropulsion is a useful technique for removing small stones and mineral debris in dogs and cats. The maximum size of cystoliths that can be retrieved is approximately 1 mm in male cats, 3 mm in female cats, 3 mm in male dogs, and 10 mm in female dogs.2 A red rubber catheter can be used to determine urethral size and estimate if cystoliths are likely to pass. Cystoscopic basket retrieval and laser lithotripsy can be used in combination with urohydropropulsion for complete removal of cystoliths. It is useful to have cystoscopy equipment available when performing urohydropropulsion, so that if all cystoliths cannot be retrieved immediate conversion to a cystoscopic technique can occur. In small male dogs and cats, a percutaneous cystolithotomy approach allows cystoscopic access to the bladder through the body wall, instead of the urethra, with only a small incision in the bladder wall.

Long term approach to managing cystoliths

The most important, and often overlooked, aspect of managing cystoliths is preventing recurrence. This is especially true of calcium oxalate cystoliths, as there is a high rate of recurrence of these stones.2 The second important factor in long term management is to diagnose cystolith recurrence at a point where they can be easily managed with minimally invasive intervention. For dogs and cats with calcium oxalate stones, the author recommends recheck evaluations at 3 month intervals to monitor urine pH (target pH is 6.6 to 7.5),1 urine specific gravity (target USG is <1.020 in dogs and <1.030 in cats),1 imaging of the bladder to assess stone recurrence, and serum calcium or electrolytes if indicated. Patients diagnosed with sterile struvite uroliths should have a urinalysis performed at 1 month intervals until the urine pH is <6.5 and then every 6-12 months thereafter. Patients with infection induced struvite stones should have urinalysis and culture performed monthly for 2-3 months after dissolution of the struvite stones, to confirm resolution of the infection.1 Management goals for less common stone types vary, but can be found at the University of Minnesota’s Urolith Center website.

Reference

- Lulich JP, Berent AC, Adams JL, et al. ACVIM Small animal consensus recommendations on the treatment and prevention of uroliths in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med 2016; 30:1564-74.

- Bartges JW and Callens A. Urolithiasis. Vet Clin Small Anim 2015; 45:747-768.

- Singh A, Hoddinott K, Morrison S, et a. Perioperative characteristics of dogs undergoing open versus laparoscopic-assisted cystotomy for treatment of cystic calculi: 89 cases (2011-2015). Amer Vet Med Assoc 2016; 249 (12): 1401-1407.

- Osborna CA, Lulich JP, Wilson JF, and Weiss CH. Changing paradigms in ethical issues and urolithiasis. Vet Clin Small Anim 2008; 39:93-109.