-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Kiko Bracker, DVM, DACVECC

By Kiko Bracker, DVM, DACVECC

angell.org/emergency

emergency@angell.org

617-522-7282

Patients who suffer severe traumatic injuries often have damage to multiple organ systems. For instance, 37% of dogs with pelvic fractures also had intraabdominal injuries.1 When multiple and severe injuries are present the question will arise: When should the patient be taken to surgery and what should be repaired first? Achieving cardiovascular stability before pursuing anesthesia and repair has always been the sensible rule of thumb. This approach certainly seems logical, and has been supported by studies that showed better survival rates for patients with diaphragmatic hernia if surgery was delayed for >24 hours after the traumatic incident.2,3 But some patients have such severe traumatic injuries that they simply cannot survive for 24 hours (or even 2 hours!) without surgical intervention. In fact, surgical intervention is required in some patients to reach cardiovascular stability. Clearly this type of patient requires a different approach; an approach that requires some modification of the initial stabilization and the surgical care itself.

Damage control surgery is aimed at this fragile population of (mostly) trauma patients who need a modified approach to standard techniques and planning in order to maximize their chance of survival. The term damage control is borrowed from the US navy’s experience with keeping damaged ships afloat with temporary measures long enough for them to get to port where definitive repair can be undertaken.4 The medical translation of this idea entails a first surgery which is aimed at restoring normal physiology but not at correcting all problems. This is followed by a few days of aggressive support to strengthen the patient so they can withstand a longer surgical procedure for definitive repair of injuries that were not addressed during the first damage control surgery.

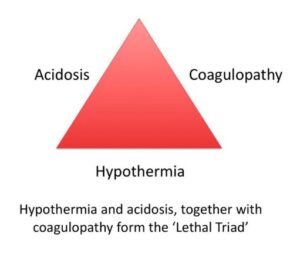

It is recognized that many trauma patients develop what is known as the lethal triad of hypotension, hypothermia and coagulopathy. Unless these problems can be corrected, a successful outcome is nearly impossible.5 The principles of damage control surgery were first put into practice in the 1980s, but the practice has been refined to now involve the aggressive resuscitation using blood products and limited crystalloid fluid in the period between the two surgeries.

Damage control surgery is broken down into four phases. Phase 1 is the preparation of the patient for surgery by limiting hemorrhage, managing hypothermia, offering transfusions of blood and plasma to limit coagulopathy and promptly getting them into the operating room. Phase 2 is the first surgery where the primary goal is to limit severe hemorrhage and control bowel leakage. Hemorrhage is limited largely by packing the abdomen with lap pads and anastomosing larger torn vessels when appropriate. Urinary diversion can be performed with indwelling urinary catheters if the urinary tract is disrupted. Tears of the bowel are closed either with sutures or stapling equipment. Severely damaged bowel is resected leaving only well perfused bowel. No attempt at this time is made to reconnect discontinuous sections of bowel – that would be done at the second definitive surgery. The abdomen is then left open with a temporary closure or barrier to limit contamination. This phase is often limited to 2 hours. Phase 3 is performed in the ICU for 12-48 hour to resolve the three components of the lethal triad (acidosis, hypothermia and coagulopathy). This is a period of aggressive resuscitation with blood products, continued warming and reversal of coagulopathy. Oxygenation is maximized with supplementation or ventilation in most cases. Overhydration with aggressive crystalloid fluids is avoided since this can result in tissue edema making abdominal closure difficult and exacerbating coagulopathy and acidosis. Phase 4 is the definitive repair of the abdominal trauma. The abdominal organs are inspected for viability and continued hemorrhage. The bowel is reconnected if needed. The lap pads controlling hemorrhage are removed and any persistent bleeding dealt with in a more controlled environment. This phase does sometimes require more than one surgery.4,5,6

Clearly the resources and expertise available in human medicine to undertake such an aggressive approach for trauma patients is hard to match in veterinary medicine. Nonetheless, we do find evidence in the veterinary literature that damage control surgery is making its way into our patient population.7,8 Like any new (and expensive) idea, it will take some time for this approach to be accepted and adopted. As critical care and surgical staffing at specialty hospitals is more and more available, there is a growing desire to split trauma surgeries into a shorter initial soft tissue surgery and then an orthopedic trauma at a later date. This is certainly a version of damage control surgery. In time, we will likely see more and more of this, and begin to approach what damage control surgery is in human medicine.

Clearly the resources and expertise available in human medicine to undertake such an aggressive approach for trauma patients is hard to match in veterinary medicine. Nonetheless, we do find evidence in the veterinary literature that damage control surgery is making its way into our patient population.7,8 Like any new (and expensive) idea, it will take some time for this approach to be accepted and adopted. As critical care and surgical staffing at specialty hospitals is more and more available, there is a growing desire to split trauma surgeries into a shorter initial soft tissue surgery and then an orthopedic trauma at a later date. This is certainly a version of damage control surgery. In time, we will likely see more and more of this, and begin to approach what damage control surgery is in human medicine.

References:

- Hoffberg JE, Koenigshof AM, Guiot LP. Retrospective evaluation of concurrent intra-abdominal injuries in dogs with traumatic pelvic fractures: 83 cases (2008-2013). J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2016 Mar-Apr;26(2):288-294

- Sullivan M, Reid J. Management of 60 cases of diaphragmatic rupture.J Small Anim Pract. 1990;31:425–430

- Boudrieau RJ, Muir WM. Pathophysiology of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Pract 1987;9:379–385

- Shapiro MB, Jenkins DH, Schwab CW, Rotondo MF. Damage control: collective review. J Trauma. 2000;49(5):969–978

- Abdominal Damage Control Surgery (lecture and proceedings). IVECCS 2015. Babak Sarani, MD, FACS, FCCM

- Rotondo MF, Zonies DH. The damage control sequence and underlying logic. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77(4):761–777

- Ghosal RDK, Bos A. Successful management of catastrophic peripheral vascular hemorrhage using massive autotransfusion and damage control surgery in a dog. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. July 2019;29(4):439-443

- Evans NA, Hardie RJ, Walker J, Bach J. Temporary abdominal packing for management of persistent hemorrhage after liver lobectomy in three dogs with hepatic neoplasia. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. September 2019;29(5):535-541