-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Daniela Vrabelova Ackley, DVM, DACVIM

By Daniela Vrabelova Ackley, DVM, DACVIM

angell.org/internalmedicine

MSPCA-Angell West

781-902-8400

This consensus was generated from published veterinary and selected human studies summarized by a panel of 7 specialists with extensive experience and training in canine hepatology.

When hepatic biopsy reveals inflammation we must be careful to differentiate between primary and secondary hepatopathy. In both cases inflammatory infiltrates are present including lymphocytic, plasmacytic or granulomatous inflammation. The key difference is that in primary hepatopathies, evidence of hepatocyte cell death is seen along with variable degrees of fibrosis and regeneration. Secondary or “reactive” hepatopathies occur due to a primary disease process elsewhere in the body, often in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), that causes inflammation in the liver without necrosis and fibrosis. This is a very important consideration when interpreting liver biopsies because the primary disease needs to be investigated and addressed. We will discuss primary chronic hepatitis in dogs (CH).

ETIOLOGY

Although there is evidence of infectious, metabolic, toxic, and immune causes of CH, most cases are idiopathic (Table 1.).

Table 1. Etiologic factors implicated in CH and relative strength of evidence based on literature.

| ETIOLOGY | SUBCATEGORY | EVIDENCE |

| Immune | Moderate-strong | |

| Toxic | Copper | Strong |

| Metabolic | Protoporphyria | Moderate (rare) |

| Alpha-1-anti-trypsin | Weak | |

| Infectious | Leptospirosis | Moderate |

| Leishmaniasis | Moderate-strong | |

| Rickettsial | Weak | |

| Mycobacteria | Moderate | |

| Histoplasmosis | Moderate | |

| Bartonella | Weak | |

| Protozoal (Neospora, Sarcocystis, Toxoplasma) | Moderate | |

| Viral | Negligible |

INFECTIOUS CAUSES

In contrast to human medicine, there is no strong evidence of a viral etiology in canine CH. Leptospirosis causes acute hepatitis but can also induce a chronic pyogranulomatous response. Ehrlichia canis has been associated with CH, and experimentally infection with Anaplasmosis spp. can cause subacute hepatitis. Multiple other systemic diseases can have hepatic involvement, but lesions are typically acute and necrotizing and part of a multisystemic disorder.

DRUGS AND TOXINS

Several drugs and toxins have been implicated in liver injury including carprofen, oxibendazole, amiodarone, aflatoxin, and cycasin. Most often they cause acute hepatopathy, but in some instances CH or cirrhosis are potential sequelae. Strong evidence indicates that phenobarbital, primidone, phenytoin, and lomustine can result in CH. In humans, it is estimated that herbal and dietary supplements are responsible for up to 18% of drug-induced liver injury! Supplement toxicity is usually difficult to prove in veterinary medicine but a complete drug history including supplements is vital.

The most common toxic injury causing CH in dogs is copper-associated CH, therefore every liver biopsy should be evaluated for abnormal hepatic copper content. Altered hepatic copper excretion in bile, excessive dietary intake or both are suspected. The panel believes that current dietary guidelines (no maximum limit for dietary copper), along with a change to more bioavailable Cu premixes in 1990s, are linked to increased hepatic Cu accumulation in dogs as noted in multiple studies.

METABOLIC CONDITIONS

Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency, caused by abnormal hepatic processing of AAT, results in hepatocyte retention of abnormally folded proteins causing CH in American and English Cocker Spaniels. It is unknown whether accumulation of hepatic AAT causes liver disease or merely reflects liver injury.

IMMUNE-MEDIATED CH

In humans, the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis relies on several criteria including serum markers (enzymes, IgG, and antinuclear, anti-mitochondrial, anti-liver and kidney microsomal antibodies), exclusion of other causes, typical histology and response to immunosuppressive treatment. It is thought to occur in genetically predisposed individuals exposed to certain triggers (pathogens, drugs, vaccinations, toxins or GI microbiome changes).

Based on available veterinary studies, an immune basis for CH is suggested by several criteria (lymphocytic infiltrate, abnormal expression of MHC class II, positive serum autoantibodies, familial history, and female predisposition). Presumptive clinical diagnosis of immune-mediated CH requires elimination of other etiologies and a favorable response to immunosuppressive treatment.

SIGNALMENT

There is strong evidence for an increased prevalence of CH in Bedlington terriers, Doberman pinschers, Labrador retrievers, dalmatians, American and English cocker spaniels, English springer spaniels, West Highland white terriers, and standard poodles. The overall mean age of onset of clinical signs is 7.2 years.

CLINICAL PATHOLOGY

Persistent (> 2 months) unexplained increases in ALT with or without other laboratory changes is the best screening test currently available for early detection of CH.

If both ALT and ALP are increased, the magnitude of ALT increase often exceeds that of ALP. There is a long subclinical phase when diagnosis should be pursued with the best chance for intervention. Once overt signs develop, they often represent complications of late stage disease with poor prognosis (portal hypertension, ascites, HE, coagulation disorders, infection, and gastroduodenal ulceration).

Hyperbilirubinemia is reported in 50% of dogs with CH and is a negative prognostic indicator. Hypoalbuminemia is a late marker of hepatic synthetic failure. Decreased BUN and cholesterol develop in approximately 40% of dogs with CH, usually once cirrhosis develops. Hypoglycemia is more often associated with acute liver failure. Serum bile acids are the most sensitive hepatic function test. However, they are not sensitive for early stages of CH and should not be used as the basis for deciding to pursue liver biopsy.

IMAGING

Hepatic ultrasonography is the most useful imaging modality for dogs with CH, however, its sensitivity is low (liver may have normal appearance in 14-57% of dogs with CH especially in early stages), and no changes are diagnostic for CH.

BIOPSY

The primary concern for any hepatic sampling is hemorrhage. Published studies including a heterogeneous group of hepatic disorders indicate a relatively low incidence of bleeding complications of 1.2-3.3%. Tests used to assess risk of hemorrhage include PCV, platelet count, PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, BMBT, and vWF in predisposed breeds. High-risk dogs (PCV < 30%, Platelets < 50,000, either PT or aPTT > 1.5 x upper limit, fibrinogen < 100 mg/dl, BMBT > 5 min, vWF < 50%) should have laparoscopic liver biopsy where tissue injury is minor compared to surgery and hemostasis can be more tightly controlled compared to ultrasound-guided needle biopsy. Patients should be hospitalized overnight after a liver biopsy to monitor for hemorrhage or other complications. There is not enough evidence to recommend routine prophylaxis with fresh frozen plasma, other blood products or vitamin K and their use should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Fine needle aspirates have no role in the definitive diagnosis of CH, because they often miss inflammatory infiltrates, extent of fibrosis, or abnormal copper accumulation.

Laparotomy is indicated if there is a concern for extra-hepatic biliary duct obstruction (EHBDO), severe gallbladder pathology or a vascular anomaly.

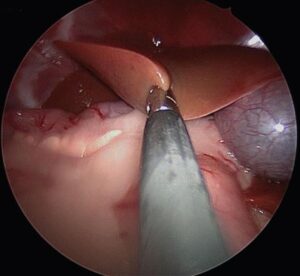

Laparoscopy is the method of choice for liver biopsy in dogs with suspected CH, as this minimally invasive method enables gross evaluation of the liver, extra-hepatic biliary system, and safe acquisition of large targeted biopsies from multiple liver lobes (Pic. 1.). A minimum of 5 biopsies from at least 2 liver lobes should be obtained for histopathology (3), aerobic/anaerobic culture (1) and quantitative copper analysis (1). Ultrasound-guided hepatic biopsy is least invasive, but small sample size frequently compromises diagnosis.

Pic. 1. Laparoscopic liver biopsy in a 2-year-old MC Havanese (McDevitt: Short-term clinical outcome of laparoscopic liver biopsy in dogs: 106 cases; JAVMA 248, No.I, January 2016)

TREATMENT

If thorough diagnostic investigation fails to find an etiology, then treatment with nonspecific hepatoprotective agents such as ursodeoxycholic acid and S-adenosylmethionine may be indicated. Beneficial effects of Silymarin were not proven in human studies therefore it is not recommended. There is limited evidence of the efficacy of vitamin E in CH in dogs.

Any increase in hepatic copper should be treated with D-penicillamine (the chelator of choice) and a copper-restricted diet, likely for months to years.

Studies support the existence of a subset of dogs with CH that respond to immunosuppressive treatments. However, not enough evidence is available to recommend an optimal immunosuppressive protocol. Corticosteroids are efficacious as a first-line treatment, but carry many side effects problematic in dogs with advanced liver injury (sodium and water retention that provoke ascites, catabolism, risk for enteric ulceration precipitating hepatic encephalopathy, hypercoagulability). Some panel members combine corticosteroids with azathioprine or cyclosporine to enable more rapid tapering of steroids to every other day anti-inflammatory doses. For most experts, maintenance on the second drug alone was the goal. Some experts use single agent cyclosporine twice daily as first-line treatment to avoid the adverse effects of corticosteroids. My personal experience with cyclosporine (Atopica) for treatment of CH has been excellent. Mycophenolate also has been used by panel members as a first- or second-line treatment and in combination with steroids. The length of time to remission and whether or not lifelong maintenance therapy is necessary is undefined.

PROGNOSIS

Dogs with CH do not typically go into spontaneous remission and there is a large amount of evidence that once diagnosed, histological lesions of CH progress and many dogs die from causes related to their hepatic disease. In multiple studies mean survival time was 561 ± 268 days. In dogs with cirrhosis, survival is considerably shorter (23 ± 23 days). Factors associated with poor prognosis include hyperbilirubinemia, prolonged PT and aPTT, hypoalbuminemia, the presence of ascites and the degree of fibrosis on biopsy.

TAKE HOME POINTS

Many dogs have increase in ALT, when should I be worried?

- Predisposed breeds

- Progressive increase during serial evaluations

- ALT greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal

- Any increase in bilirubin