-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Michele James, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)

By Michele James, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)

angell.org/neurology

neurology@angell.org

617-541-5140

Overview

Discospondylitis is an inflammatory disease of the spine characterized by infection of the intervertebral disc, adjacent vertebral endplates, and vertebral bodies. The infection typically develops secondary to hematogenous spread of bacteria from a distant site, such as the urinary tract, prostate, mouth, or skin. In rare cases, the infection can originate from a migrating foreign body (i.e. grass awn), penetrating trauma, surgery, or epidural injection. The most commonly reported bacterial etiologic agents are Staphylococcus spp (S. aureus and S. intermedius), however Streptococcus spp, Brucella canis, and Escherichia coli, have been routinely isolated. Salmonella, Enterobacter, Nocardia, and variable fungal organisms have also been reported. Dogs are more commonly affected, though discospondylitis has been described in cats, horses, ruminants, and pigs. In a large study by Burkett at al. examining the signalment and clinical features of discospondylitis in over 500 dogs; male dogs, older dogs, and purebred dogs were more likely to be affected with the disease than their counterparts. Great Danes, German Shepherds, and Labrador Retrievers appear to be overrepresented in the literature.

Presentation

Patients with discospondylitis can have variable clinical signs, though spinal hyperesthesia is the most commonly reported physical exam finding. Some patients may also present with non-specific systemic signs, including lethargy, fever, and decreased appetite. Owners may report waxing and waning clinical signs that appear to worsen with physical activity. Depending on the location, duration, and severity of the lesion, some patients may present with minimal to no appreciable pain, whereas others may have more severe neurologic dysfunction ranging from ataxia to plegia. Neurologic deficits, such as paresis/plegia, are rarely observed in the absence of more serious complications such as vertebral luxations, pathologic fractures, and/or spinal empyema.

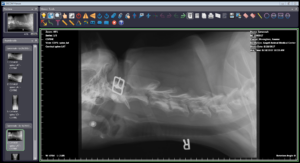

Figure 1. Lateral cervical radiograph of a 10 month old German Shepherd dog with discospodylitis at C3-4. There is osteolysis of the vertebral end plates and moderate sclerosis of the adjacent bone

Diagnosis

Discospondylitis is clinically diagnosed by radiography, though radiographic changes may lag several days to weeks after onset of infection. Radiographic findings include osteolysis of vertebral endplates, sclerosis of adjacent bone, and narrowing of the intervertebral disc space (Figure 1). Advanced imaging modalities, namely CT and MRI, are able to identify discospondylitis sites earlier in the disease process prior to radiographic diagnosis. The lumbosacral disc space is reported to be one of the most commonly affected sites, though the thoracolumbar and cervical spine is also frequently affected.

Positive microbial culture results not only help to support a diagnosis of discospondylitis, but also help to guide treatment. Urinalysis and urine cultures should be submitted in all patients suspected of having discospondylitis. Blood cultures may also be submitted, however, in the author’s experience, these have been of low yield, particularly if the patient is not febrile at the time of diagnosis. Fine needle aspirate of an affected disc space may be considered in hopes of determining the microbial profile of an infection, but diagnostic yield is reported to vary greatly and in the author’s experience has also been low yield. Though Brucella accounts for less than 10% of discospondylitis cases in dogs, due to the risk of zoonotic potential of Brucellosis, Brucella titers should be performed in all canine patients suspected of discospondylitis. Brucella is more prevalent in male intact dogs in the southeastern United States.

Treatment

Medical management with targeted antibiotic therapy, ideally based on isolation of an organism, is the mainstay of treatment for discospondylitis. Rarely, in cases with severe neurologic deficits, surgical decompression and/or stabilization may also be warranted. Since isolation of an organism may not occur in 50-60% of cases, empirical treatment with antibiotics known to have good bone penetration and known to be effective against Staphylococcus and Streptococcus is acceptable and recommended. This includes potentiated cephalosporins (i.e. Cephalexin 30 mg/kg PO Q8hr) or potentiated penicillins (i.e. Clavamox/Augmentin 15 mg/kg PO Q12hr). Analgesics such as Gabapentin, Tramadol, and/or NSAIDs may also be prescribed early in treatment to help address hyperesthesia. Patients should also be exercise-restricted for 4 to 6 weeks following diagnosis.

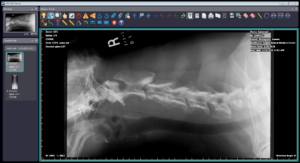

Figure 2. Lateral cervical radiograph of the same German Shepherd dog pictured in Figure 1 following 6 months of antibiotic treatment for previously diagnosed discospondylitis. There is anykylosis of the C3 and C4 vertebral bodies and reduction in the degree of osteosclerosis of the C3-4 vertebral end plates.

Patients should experience a resolution of clinical signs within 3-5 days of starting antibiotic therapy. If this does not occur, then additional diagnostic work up (i.e. fine needle aspirate of the disc space, surgical biopsy, and/or fungal testing) may be indicated to determine if a change in antimicrobial therapy is needed in the event of a resistant bacterial infection or underlying fungal infection.

Patients should be treated for ideally 2-4 weeks following resolution of both clinical signs and radiographic resolution of the infection, as premature discontinuation of antimicrobial therapy results in a relapse of clinical signs. For many animals, radiographic resolution may take several months or longer to occur; therefore most patients will need to be on antibiotic therapy for 6 months to a year or longer. The author recommends recheck radiographs 2 months following initiation of treatment and then every 3-4 months until evidence of bony lysis has disappeared and/or vertebral fusion has occurred on two consecutive recheck radiographs. Healed discospondylitis on radiographs is characterized by anykylosis and the replacement of lytic bone with osseous proliferation (Figure 2).

Fungal infections should be considered in patients not responding to empirical antibiotic therapy. German Shepherds are predisposed to Aspergillus infection. In cases of fungal discospondylitits, early treatment with an anti-fungal microbial is recommended (i.e. Itraconazole 5 mg/kg PO Q24hr).

Brucellosis is an incurable disease, however some infected dogs may respond favorably to combination antimicrobial therapy (i.e. Enrofloxacin 10-20 mg/kg PO Q24hr and Doxycycline 5 mg/kg PO Q12hr). It is recommended that infected patients be castrated or spayed and owners and other people in contact with the patient should take appropriate measures to prevent exposure (i.e. appropriate hand washing, etc.). Brucellosis is a reportable disease in many states, including Massachusetts.

Prognosis

For a large majority of cases, the prognosis for bacterial discocospondylitis is very good, particularly if treated early and prior to severe neurologic deficits. However, owners should be counseled on the need for long term antibiotic therapy and repeat radiographs. Although Brucellosis is incurable, patients may be able to be managed long term with lifelong antibiotic treatment. Unfortunately, fungal discospondylitis has a guarded to poor prognosis due the risk of disseminated disease.

References:

Burket BA, Kerwin SC, Hosgood GL, Pechman RD, Fontenelle JP. Signalment and clinical features of diskospondylitis in dogs: 513 cases (1980-2001). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2005; 227 (2):268-75.

Finnen A, Blond L, Parent J. Cervical discospondylitis in 2 Great Dane puppies following routine surgery. The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 2012; 53(5):531-534.

Gorgi A, O’Brien D. Diskospondylitis in Dogs. Standards of Care: Emergency and Critical Care Medicine. 2007; 9.5: 11-15.

Packer RA, Coates JR, Cook CR, Lattimer JC, O’Brien DP. Sublumbar abscess and diskospondylitis in a cat. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound. 2005; 46(5):396-399.

Ruoff CM, Kerwin SC, Taylor AR. Diagnostic imaging of discospondylitis. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 2018; 48(1):85-94.

Van Wie E, Chen A, Thomovsky S, Tucker R. Successful long term use of itraconazole for the treatment of aspergillus diskospondylitis in a dog. Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine. 2013; Article ID 907276, 4 pages.