-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Patty J. Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (Anatomic and Clinical Pathology)

Patty J. Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (Anatomic and Clinical Pathology)

www.angell.org/lab

pathology@angell.org

617 541-5014

Summary

Granulocytic anaplasmosis should be included on a differential diagnoses list for any cat that lives in an Ixodes spp. endemic area with potential tick exposure and that presents with acute or intermittent, vague symptoms of lethargy, anorexia, and fever. In the northeastern USA, infections are most common in the months of May, June, and October. Clinicopathologic findings may include anemia, neutrophilia or neutropenia, lymphopenia, hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia, hypoalbuminemia, or hyperalbuminemia. Diagnosis of anaplasmosis is made by identification of morulae in neutrophils on peripheral blood smears, and/or positive PCR or serologic results, and response to treatment. An effective treatment is doxycycline administered orally at a dosage of 5 mg/kg twice a day for 14 to 28 days. Prevention strategy includes limiting outdoor access, use of topical acaricides and/or tick repellents, and daily tick checks.

With tick-borne diseases in small animal practice, a major focus is prevention, diagnosis and treatment of these conditions in dogs. However, it is important to recognize that tick-borne diseases also occur in cats. In 2015, we published a retrospective study of granulocytic anaplasmosis in 16 cats in the northeastern USA.1 In this brief article, I will review the findings from the retrospective study as well as other clinically relevant information about anaplasmosis to increase awareness of this emerging tick-borne rickettsial disease in cats.

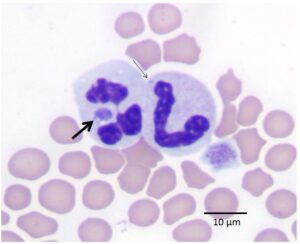

Figure 1: Peripheral blood smear from a cat infected with A. phagocytophilum. The thick black arrow shows a morula within the cytoplasm of a neutrophil. The thin black arrow shows a Döhle body for comparison. Wright-Giemsa stain.

Cause and Transmission

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is a rickettsial bacterium that is transmitted via the bite of an infected Ixodes spp. tick, specifically Ixodes scapularis in the northeastern USA.2 Approximately 24 to 48 hours of tick attachment is required for transmission.3 Infections are most common in the late spring (April through June) and fall (especially October) when nymph and adult ticks are most active.1 The organism has been reported to affect horses, dogs, cats, ruminants, and people. After transmission, the organism infects blood neutrophils forming intracellular inclusions known as morulae (Latin translation: mulberry, which describes their appearance). Microscopic identification of these distinctive mini-mulberries in neutrophils on Wright-Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smears was the method by which we identified the first cases of feline anaplasmosis at Angell Animal Medical Center (see Figure 1).

Note: This organism was previously called Ehrlichia equi, so readers may find this organism name and the disease name granulocytic ehrlichiosis used in older literature.2

Signalment and Clinical Signs

The mean age of cats with anaplasmosis in the retrospective study was 4.1 years (range of 4 months to 13 years).1 Both male and female cats were affected and all cats had outdoor access. The most commonly observed clinical signs included lethargy, anorexia, fever, and ocular abnormalities (conjunctivitis and elevated nictitating membranes). Ocular signs are likely the result of systemic inflammation. Less commonly reported clinical signs included dehydration, tachycardia, abdominal discomfort, and infrequently, ataxia and hepatosplenomegaly. The mean duration of clinical signs prior to presentation in the cats in the retrospective study was 2.8 days (range of 1 to 7 days).1 Because the clinical signs are relatively non-specific and can be intermittent, prompt diagnosis of anaplasmosis can be challenging.

Clinicopathologic Findings

Reported hematologic abnormalities in infected cats included mature neutrophilia or neutropenia, lymphopenia and less commonly, mild to moderate normocytic, normochromic anemia.1,4 Interestingly, thrombocytopenia was not confirmed in any of the 16 cats in the retrospective study despite the fact that 87% of dogs with clinical anaplasmosis presented with mild to moderate thrombocytopenia in one study.5 Three of 5 cats with granulocytic anaplasmosis in another case report were reportedly thrombocytopenic; however, 1 of 3 cases had clumped platelets.6 The previous report of thrombocytopenia may be accurate or may be falsely low automated platelet counts due to the tendency of feline platelets to clump in vitro.7 Additionally, it is possible that although platelet estimates were considered adequate in the cases described in our study, some may have had mild thrombocytopenia that was not appreciated in the blood smear review. Additional investigations of cats with granulocytic anaplasmosis are needed to determine if true thrombocytopenia exists.

No specific biochemical changes were reported in cats with anaplasmosis. Biochemical abnormalities in infected cats may include hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia, and hypoalbuminemia or hyperalbuminemia. Urinalysis may reveal proteinuria although this has not been a consistent finding in cats.

Diagnosis

CBC, biochemistry panel, and urinalysis are recommended as a minimum database. An expeditious and inexpensive method of establishing a presumptive diagnosis is the identification of morulae within the cytoplasm of neutrophils. When present, morulae may be found in a relatively low proportion (5 to 20%) of the neutrophils in a peripheral blood smear, thus thorough microscopic blood smear review is recommended to increase the chance of detecting the organism. Morulae appear in the cytoplasm of neutrophils as irregularly round, coarsely granular basophilic structures ranging in size from 1 to 3 µm (Figure 1). They must be differentiated from Döhle bodies, which appear as pale blue, round to linear structures in the cytoplasm representing aggregation of rough endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 1). Döhle bodies may be observed in normal feline neutrophils in low numbers, in early toxic change, or as an artifact of storage. Morulae are usually not detected beyond the first week of infection. Identification requires good microscopic resolution and personnel skilled at recognizing morulae. Because these conditions may not be available in all practices, PCR analysis of peripheral blood submitted in a lavender top (EDTA) tube is the test that most general practice veterinarians rely on to make the diagnosis. In our study, anaplasmosis was confirmed via PCR analysis using the Feline Flea and Tick-Borne Disease Profile Fast Panel™ PCR test (ANTECH® Diagnostics). IDEXX Laboratories and some university laboratories offer similar testing. It is important to note that finding morulae via peripheral blood smear review and PCR testing can detect early infection when serologic tests are negative, but a negative PCR result or absence of morulae does not rule out exposure or infection for the reasons stated above and in patients that have already received antibiotic therapy. ELISA or IFA Serology may be a useful diagnostic test to confirm exposure in more chronic cases. Typically, serologic titers will not become positive until at least 8 days post-infection. Unlike PCR and morulae identification, positive serology indicates exposure and not necessarily active infection. A 4-fold increase in convalescent titers after 14 days supports a diagnosis of active infection.8

Treatment

An effective treatment for feline anaplasmosis is doxycycline administered orally at a dosage of 5 mg/kg twice a day for 14 to 28 days. Be aware that doxycycline can cause esophageal erosion, inflammation and stricture in cat. For this reason, oral doses should be followed with sufficient fluid to ensure that the medication gets into the stomach. Anorexia, vomiting and diarrhea are the most commonly reported side effects of doxycycline administration. An increase in serum liver enzymes (ALT, ALP) may also occur.

Prevention

The key to disease prevention is decreasing exposure to ticks and/or preventing transmission via tick bites. This can be accomplished by limiting a cat’s outdoor access. When limiting outdoor access is not feasible, use of topical acaricides or tick repellents and daily tick checks are recommended.

References

- Savidge C, Ewing P, Andrews J, Aucoin D, Lappin M, Moroff S. Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection of domestic cats: 16 cases from the northeastern USA. J Feline Med Surg 2015 Feb 13.

- Woldehiwet The natural history of Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Vet Parasitol 2010;167:108-122.

- Katavolos P, Armstrong P, Dawson J, et al. Duration of Tick Attachment Required for Transmission of Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis 1998; 177: 1422-1425.

- Bjoersdorff A, Svendenius L, Owens JH, et al. Feline granulocytic ehrlichiosis- a report of a new clinical entity and characterisation of the infectious agent. J Small Anim Pract 1999; 40: 20-24.

- Kohn B, Galke D, Beelitz P, et al. Clinical Features of Canine Anaplasmosis in 18 Naturally Infected Dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22: 1289-1295.

- Lappin MR, Breitschwerdt EB, Jensen WA, et al. Molecular and serologic evidence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in cats in North America. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004; 225: 893-896.

- Willard M and Tvedten H. Small Animal Clinical Diagnosis by Laboratory Methods. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2004, pp 98-99.

- Bakken JS, Dumler S. Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 31: 554-560.