-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

by Klaus E. Loft, DVM

by Klaus E. Loft, DVM

dermatology@angell.org

angell.org/dermatology

617-524-5733

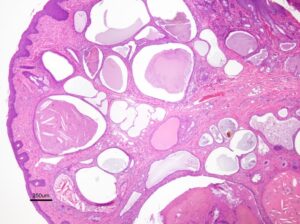

Ceruminous cysts in the ear canals of cats originate in the ceruminous glands of the meatic lining (Figure 1) and can cause mild to severe symptoms of secondary otitis externa and media caused by the obstructive effect of the cysts interfering with normal self-cleaning1.

Figure 1: Histopathology from a cystomatosis cat, note the large cystic lesions with amorphous material

Feline cystomatosis typically presents clinically with characteristic bluish-black cystic lesions on the concave pinna, tragus region and the vertical auditory meatus of one or both ears. Cysts can extend to the level of the horizontal canal (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Dark cystic lesions on the concave pinna and extending into the tragus zone of right ear of a cat with cystomatosis

The literature on the condition, reports cystomatosis to be a rare clinical finding and seen mostly in middle aged to older cats with a tentative genetic predisposition in Persians and Himalayans.1,2,3 No known etiology is identified at this point. Nomenclatures have historically been varied, including apocrine cysts/tumors,4 cystadenomatosis, ceruminous cystomatosis,1,5 benign melanotic ceruminous gland adenomas3 and ceruminous adenomas (multi-centric/focal), apocrine hyperplasia.6,7 These ceruminous glands are modified sweat glands and are generally more prevalent in the upper half of the meatic horizontal canal.3,7 The modified sweat secretions are atrichial or paratrichial (not associated with hair follicles). Some text books report that the condition is mostly cosmetic in nature. However in our cases the secondary infections and potential progression into neoplasia disagree with these observations.

Angell Dermatology is conducting a pilot study of cats with cystomatosis who are presenting for various degrees of secondary otitis externa. The aim of the study is to report on the incidence and signalment of cases as well as PCR-status of feline papillomavirus in affected tissue. So far we have findings from 21 cats (38 ears affected with cystomatosis), but we will continue collecting cases until we have sufficient data to publish a more in depth statistical analysis of the possible etiology and predisposing or protecting factors for this condition.

We reviewed the medical records of 21 cats seen in the time span from January 2011 to this point with clinical signs consistent with cystomatosis and so far have confirmed fourteen cases by histopathology (26 ears). Pearson’s Chi-Square test was performed on data collected from medical records for “Goodness of fit”. Tissue from thirteen cats (21 ears) was additionally tested for presence of DNA material from papilloma virus by Dr. C. Lange’s laboratory.

Cystomatosis was noted in 0.06% of the cats referred to the Angell Dermatology Service in the first phase of the study January 2011 through 2013; all data have not yet been analyzed for 2014 cases.

The following data does include all 21 cases seen at Angell Dermatology; Breeds affected by cystomatosis included Domestic Shorthair (DSH) (10 cats; 47.6%), Domestic Longhair (DLH) (2 cats; 9.5%), Domestic Mediumhair (DMH) (6 cats; 28.5%), and Abyssinian, Persian & Himalayan (1 cat each; 4.7%). The average age at diagnosis was 11.47 years (range: 4.0 to 15.5 years). The age of diagnosis was defined as the first finding in the medical records of changes consistent with the condition and/or histopathology reports confirming the diagnosis. Cystomatosis was found in eleven spayed females (52.4%), seven castrated males (33.3%) one intact female and one intact male (4.7%). Tissue from 2 cats tested positive for Feline papillomavirus-2 (FcaPV2) and samples from 19 ears was negative for a broad range of PCR papilloma virus DNA types, indicating that papilloma virus is unlikely to have been a major factor in the development of the cysts.

Cystomatosis were observed on body areas other than ears in only one cat (face/lip) the 21 cases although the literature suggests that similar cystic lesions can be found around eyes and lips1 (Figure 3) and are not uncommon among cats affected with cystomatosis.

Six of the histopathological examine cases (7 ears, 26.9%) progressed from benign cysts to inflamed adenocarcinoma (n=5, 19.2%), mast cell tumor grade II (n=1, 3.9%) or squamous carcinoma (n=1, 3.9%). One of the 2 samples positive for FcaPV2 was from the cat with mast cell neoplasia, and this finding raises the question; does cystomatosis increase the risk of neoplastic transformation? At this point further studies are needed to investigate this aspect of the condition. We have tested for the feline papilloma virus in the cystic tissue to potentially link the cystic and/or neoplastic tissue to a viral etiology, but at this time no such connection can be made or ruled out due to the limited number of samples tested.

In the first two years of our pilot study, cystomatosis was found to be more significantly prevalent in female spayed cats (p-value 0.0101, cut-off p-value 0.05). This finding is likely a reflection of the cat population referred to the dermatology service rather than a true increased prevalence and we hope additional cases and analysis will allow for a stronger statistical evaluation and we conclude that there does not appear to be a correlation between breed of cat and cystomatosis as previous researchers have suggested for; Persian and Himalayan cats,3 but with a limited number of cats in our study, additional research should be conducted in order to confirm or disprove our findings. Only two of the tested tissues had evidence of papilloma virus DNA suggesting that the papilloma virus did not play a role in the etiology. In six cats and in seven different ears a cancerous process was found.

Cystomatosis does not appear to be associated with other medical disorders in the studied cases. Further studies are needed to investigate the etiology of cystomatosis.

We have been able to successfully relieve a large amount of the discomfort and secondary otitis externa symptoms for these cats using CO-2 laser treatment of the cysts within the pinna, vertical and even into the horizontal meatic canal. The technique does require some modification of existing CO-2 lasers, but has become a very nice treatment option for these patients.

If you think you have a patient who might be a candidate for inclusion in the otology study, please contact Dr. Loft at Dermatology@angell.org. Currently no financial compensation or reduction in cost of service is available.

Thank you to Dr. Christian Lange, Harvard Medical School Boston, MA for his expertise in PCR testing and to Dr. Martin Coster from Angell Ophthalmology for the images of non-otic cystomatosis. Dr. Pam Mouser provided great help and insight with the histopathology and provided the histopathologic image.

All data are reporting the first 2 years of the study (data not yet analyzed for full study period)

References:

- W.H. Miller, C.G. Griffin & K.L. Campbell; ”Diseases of eyelids, claws, anal sacs and ears” Chapter 19, p.752-53. Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 7th edition, Elsevier, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 2013.

- T.L. Gross, P.J. Ihrke, E.J. Walder & V.K. Affolter; “Skin disease of the dog and cat”. Second Edition, Blackwell Science 2005, p 666-674.

- R.G. Harvey, J. Harari & A.J. Delauche; “Ear disease of the cat and dog” Iowa state University Press, Ames, Iowa, USA, 2001, p. 107.

- É. Guaguère & P. Prélaud; “A practical guide to Feline dermatology” Merial 1999, p.22.3

- D. Duclos; ”Lasers in veterinary dermatology” Chapter in Veterinary Clinics of North America, Small Animal Practice(Editor K.L. Campbell), Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006 volume 36, p.15-37.

- F. Kristensen, J.O.G. Jacobsen & T. Eriksen; ”Otology in cats & dogs” DSR Tryk, Frederiksberg, Danmark, 1996, p.66.

- A Yager & B. P. Wilcock; “Color Atlas and Text of Surgical Pathology of the Dog and Cat Dermatopathology and Skin Tumors,” St. Louis: Mosby-Year book; 1994 p. 407-10.