-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Martin Coster, DVM, MS, DACVO

angell.org/eyes

ophthalmology@angell.org

617-541-5095

Eosinophilic keratitis and eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis are inflammatory conditions of the cornea and/or conjunctiva, most commonly diagnosed in cats but also recognized in horses.

The exact reason for the development of inflammation is unknown. Causative theories include feline (or equine) herpesvirus infection, autoimmune disease, and allergy.

Clinical Signs

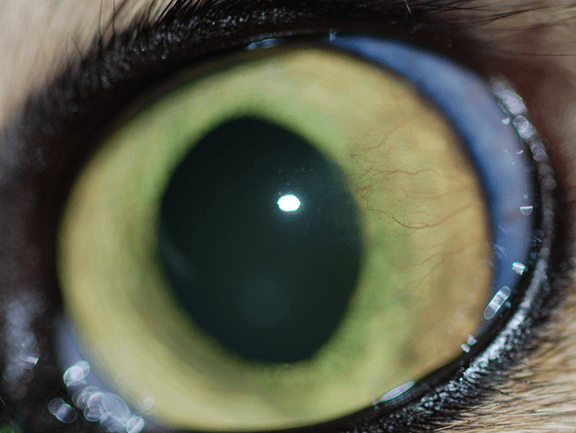

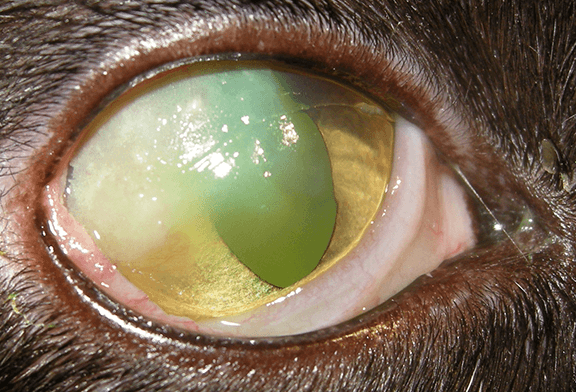

In the cat, this disease has a classic, almost pathognomonic, appearance (Figure 1). There are usually raised, white/yellow plaques on the surface of the cornea (often at the superior-lateral aspect), along with corneal vascularization and sometimes granulation tissue (thick proliferation of red blood vessels and scar tissue). Corneal ulcers around the edges of the plaques can occur and are a frequent cause of pain, although the primary lesions are often not associated with symptoms of pain. On fluorescein dye staining, the plaques will often take up stain, along with any surface ulceration (Figure 2).

Figure 1- Eosinophilic keratitis in the right eye of a cat; note the hazy corneal opacity in the superior-lateral aspect with focal white, raised plaques.

Figure 2- Eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis in the right eye of a cat. Following fluorescein dye staining, the eosinophilic plaques appear yellow-green. Note the superior-lateral perilimbal superficial corneal ulcer. Conjunctivcal involvement to this extent is relatively rare in the cat.

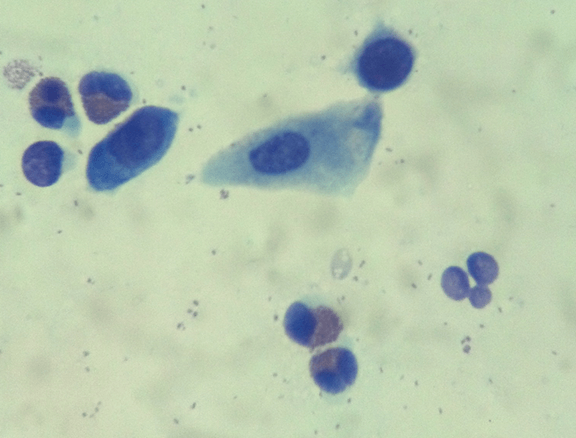

Figure 3- Corneoconjunctival cytology of a cat affected with eosinophilic keratitis; note the presence of numerous eosinophils along with normal epithelial cells.

Although the appearance of this disease can be pathognomonic, the definitive diagnosis relies upon corneal cytology. Techniques for obtaining diagnostic samples include Microbrush® applicator, cotton swabs, Kimura spatula, or the blunt (handle) end of a scalpel blade. Harvesting of a plaque is most likely to confirm the presence of eosinophils (Figure 3).

Besides the immediate pain of corneal ulcers and corneal surface inflammation, secondary bacterial infections can result from eosinophilic keratitis. For this reason, a topical antibiotic is often prescribed. Infection can lead to loss of vision or even the eye.

Even without ulceration, over time the disease can progress to cover the corneal surface, affecting vision. Even when medically controlled, scar tissue may remain at the previous location of inflammation which can impair vision.

Treatment Options

Since this syndrome is not well understood and may have various causes, there are numerous therapies available, and various combinations of medications may be tried until the most effective regimen is determined.

Megestrol acetate, a progesterone derivative, has been widely used for this condition, usually with excellent and fast results when given orally. However, there are uncommon but serious potential complications, due to its steroid effects. Mammary gland tumors, diabetes, behavior changes (hyperactivity and aggression), increased appetite, vomiting, and diarrhea are possible and should be closely monitored for, if therapy is initiated. The minimum effective dose for response, with quick tapering, is recommended. The author typically starts with 2.5 to 5 mg per cat once a day for a week, weaning down over a few weeks to 2.5 to 5 mg per cat once every 7 to 10 days. In the author’s experience, longterm control can be achieved with single oral dosing of 2.5 to 5 mg every 10 to 30 days, with recurrence common in cats in which this is discontinued. Baseline blood glucose and glucose monitoring along with mammary palpation are performed at every frequent recheck.

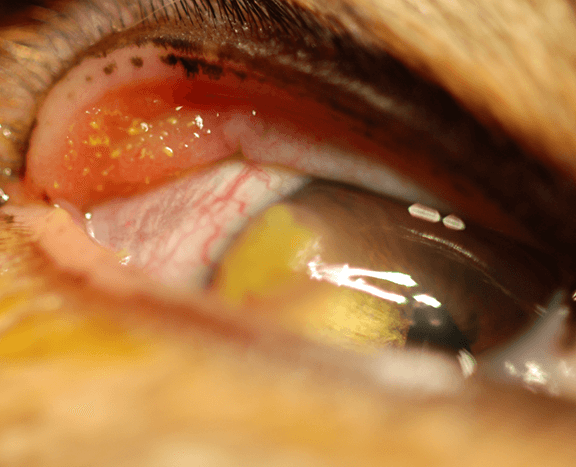

Recently, a pilot study conducted between Purdue University and Angell Animal Medical Center examined the efficacy of a topical formulation of megestrol acetate on eosinophilic keratitis in cats. Compounded into a 0.5% solution, excellent results were observed without appreciable side effects (Figures 4 and 5). Despite the steroidal properties of megestrol acetate, corneal ulcers associated with eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis healed with this therapy. Three times daily therapy was required initially, tapering over a few months to every other day or every third day dosing. Longterm therapy is likely necessary as recurrence can occur with less frequency dosing (Figure 6). This has become the author’s treatment of choice, along with a topical antibiotic in the presence of ulceration.

Figure 4 – Eosinophilic keratitis in the left eye of a cat. Figure 5 is of the same eye following topical megestrol acetate therapy.

Figure 6 – Recurrence of eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis in the left eye of a cat following tapering of topical megestrol acetate therapy. Note the limbal raised plaques, stained yellow-green with fluorescein dye.

Antibiotics, such as erythromycin ointment or tobramycin drops q8h, should be used to prevent or control secondary bacterial infections, especially when corneal ulceration is present. Triple antibiotic products containing neomycin and polymyxin are avoided by some, due to concerns with anaphylaxis in the cat.

As alternatives to megestrol acetate, topical steroids such as prednisolone acetate or dexamethasone can be used for severe cases, at frequencies appropriate to the level of inflammation (q6h to q24h). However there is a risk of worsening corneal ulceration or infection with these medications and so careful monitoring is essential.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (such as flurbiprofen or diclofenac) can be used to ameliorate the risk to the cornea; these are considered safer but less effective than topical steroids.

Topical 1% or 2% cyclosporine (or Optimmune® ointment; Merk Animal Health) can be used as an immune modulating agent. Response varies but risks are minimal.

Finally, given the potential for feline herpesvirus as a causative or exacerbating agent with eosinophilic keratitis, some ophthalmologists consider anti-herpesviral therapy the mainstay for treatment. Topical options include cidofovir q12h, idoxuridine q6h, and trifluridine (Viroptic®; Pfizer) q6h, and oral famciclovir may also be considered.

Summary

In summary, eosinophilic keratitis can be a chronic, painful, blinding disease in cats yet fortunately can be easily recognized by its clinical appearance. Definitive diagnosis relies on cytology. Treatment options are varied and often needed longterm, but excellent success can be achieved with topical anti-inflammatory agents, particularly with the recent advent of compounded topical megestrol acetate. However, referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist is still advised for management of these cases.

For more information on Angell’s Ophthalmology Service, please visit angell.org/eyes or contact us at 617-541-5095 or ophthalmology@angell.org.

Further Reading:

Use of an ophthalmic formulation of megestrol acetate for the treatment of eosinophilic keratitis in cats. Stiles J, Coster M. Vet Ophthalmol. 2016 Jul;19 Suppl 1:86-90.

Eosinophilic keratitis and keratoconjunctivitis in a 7-year-old domestic shorthaired cat Hodges A. Can Vet J. 2005 Nov; 46(11): 1034–1035.

Feline eosinophilic keratoconjunctivitis: a retrospective study of 45 cases (56 eyes). Dean E, Meunier V. J Feline Med Surg. 2013 Aug;15(8):661-6. doi: 10.1177/1098612X12472181.

Feline eosinophilic conjunctivitis. Allgoewer I, Schäffer EH, Stockhaus C, Vögtlin A. Vet Ophthalmol. 2001 Mar;4(1):69-74.

Detection of feline herpesvirus 1 DNA in corneas of cats with eosinophilic keratitis or corneal sequestration. Nasisse MP, Glover TL, Moore CP, Weigler BJ. Am J Vet Res. 1998 Jul;59(7):856-8.

Equine eosinophilic keratitis in horses: 28 cases (2003–2013) Edwards S, Clode AB, Gilger BC. Clin Case Rep. 2015 Dec; 3(12): 1000–1006.

An unusual chronic keratoconjunctivitis in the cat. Bedford PGC, Cotchin E. J Small Anim Pract 1983;24:85-102.

Feline corneal disease. Moore PA. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2005;20:83-93.