-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Martin Coster, DVM, MS, DACVO

Martin Coster, DVM, MS, DACVO

www.angell.org/eyes

ophthalmology@angell.org

617-541-5095

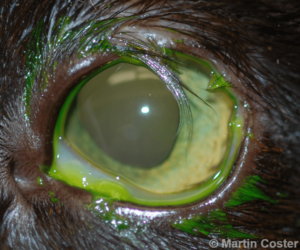

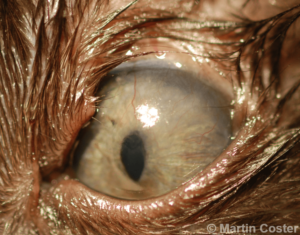

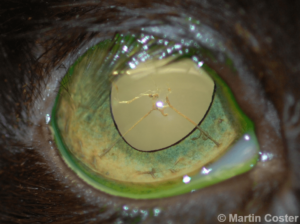

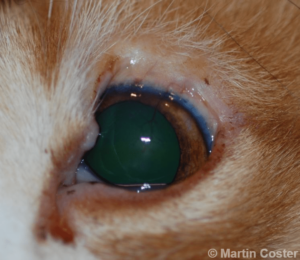

Eyelid agenesis, or eyelid coloboma, is a congenital defect of the eyelid in which typically the upper lateral eyelid is not formed (Belhorn et al, 1971). Eyelid agenesis is most common in the cat, and is rare in dogs. The result is that conjunctiva is contiguous with skin, and this leads to exposure of the cornea from incomplete blinking, as well as irritation from contact of hairs with the cornea (trichiasis; Figure 1). Keratitis (vascularization, ulceration, scarring, and/or corneal pigmentation) can then occur, and over time vision can be affected (Figures 2 & 3). Catastrophic corneal infection is also a possibility. The lesion is typically bilateral, although the eyelids can be affected to differing degrees. Eyelid agenesis may also be associated with other congenital lesions (e.g. persistent pupillary membranes; Figure 4).

Figure 1 – Superior-lateral eyelid agenesis of the left eye of a cat; note the lack of a formed eyelid margin along with trichiasis – numerous long hairs lie on the corneal surface. Fluorescein dye has been applied to the eye.

Figure 2 – Superior eyelid agenesis in a cat, with exposure keratitis (corneal vascularization and scarring).

Figure 3 – Superior eyelid agenesis of the right eye of a cat; note the superior corneal pigmentation, vascularization, and generalized haze (scar tissue).

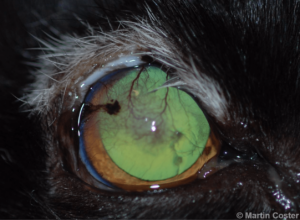

Figure 4 – Superior-lateral eyelid agenesis of the right eye of a cat; note also iris-to-lens persistent pupillary membranes.

For temporary relief from trichiasis and corneal exposure, medical management with artificial tears ointment as needed every 4-8 hours can be tried, although some cats may be irritated by the ointment base (Eördögh et al, 2015). Secondary corneal ulceration should be appropriately managed with topical antibiotics (e.g. erythromycin q6-8h) and pain control (e.g. sublingual buprenex and/or topical atropine ointment).

Numerous surgical procedures have been reported for the correction of eyelid agenesis ‑ there is not one perfect way to correct the defect. The choice of surgical technique may depend on the size of the defect, severity of secondary corneal changes, financial constraints, and outcome expectations. For very small defects or cases of limited financial resources, manual epilation (i.e., plucking the hairs) can provide temporary relief but may need to be repeated up to every month as hairs regrow.

For permanent hair destruction, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy of the conjunctival-skin margin can be very efficacious. Two freeze-thaw cycles are typically applied with a direct contact probe to the skin, although care must be taken not to over-freeze which can result in full-thickness tissue necrosis. Protection of the cornea with a corneal shield is paramount during cryotherapy.

Figure 5 shows the immediate post-operative appearance with eyelid swelling and hyperemia expected; Figure 6 is of the same cat once this resolved. Due to variability in results (potential for hair regrowth), multiple procedures may be required (Figure 7).

Figure 5 – Eyelid inflammation and swelling immediately following liquid nitrogen cryotherapy and epilation of trichiasis in feline eyelid agenesis.

Figure 6 – The same cat from Figure 5, following resolution of post-operative swelling; the eyelid defect still exists but trichiasis has been alleviated.

Figure 7 – Leukotrichia (whiteness of hair) following previous liquid nitrogen cryotherapy and epilation of trichiasis in feline agenesis. Note the ongoing trichiasis and keratitis. Cryotherapy was elected to be repeated in this case.

For definitive correction, reconstructive eyelid surgery aims to provide a functional eyelid margin, and 1-, 2-, and even 3- stage procedures have been reported. To name just a few, these including transposing part of the lower lid (e.g., the cross lid flap described by Munger and Gourley in 1981 and, more recently, a modification of the Mustardé technique described by Esson in 2001), “bucket-handle” grafting in which facial skin is transposed beneath the eyelid margin to cross to the other eyelid, and rotational skin flaps.

The author has recently had good success using the lip commissure to eyelid transposition surgery, which is a single-stage surgery. This procedure was first published in JAVMA by Dr. Pavletic in 1982 as a method of lower eyelid reconstruction in dogs. The technique was adopted for upper eyelid agenesis in cats, by Whitaker et al in 2010. In this procedure, a rotating skin flap incorporating the lip commissure is created, mobilizing the lip tissue to replace the missing eyelid. The transposed oral mucosa is sutured to the conjunctiva, the lip commissure (now shorter but still functional) is closed, and the skin graft is then closed in a routine fashion (Figure 8). In addition to providing static protection to the cornea, this lip tissue will often “blink” along with the remaining upper eyelid. Potential complications can include graft dehiscence or necrosis, ongoing trichiasis, and poor ability to blink; however most do well (Figure 9).

Figure 8 – The immediate post-operative appearance of a cat following lip commissure to eyelid transposition surgery.

Figure 9 – Six month post-operative appearance of a cat following successful lip commissure to eyelid transposition surgery.

For more information about Angell’s Ophthalmology service, please visit www.angell.org/eyes. Dr. Coster can be reached for consults or referrals at 617-541-5095 or ophthalmology@angell.org

References & Further Reading:

Belhorn RW, Barnett KC, Henkind P. Ocular colobomas in domestic cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1971 Oct 15;159(8):1015-21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4999152

Cutler NL, Beard C. A method for partial and total upper lid reconstruction. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1955; 39: 1–7.

Dziezyc J, Millichamp NJ. Surgical correction of eyelid agenesis in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1989; 25:513

Eördögh R, Schwendenwein I, Tichy A, Loncaric I, Nell B. Clinical effect of four different ointment bases on healthy cat eyes. Vet Ophthalmol. 2015 May 15. doi: 10.1111/vop.12279. [Epub ahead of print] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25975762

Esson D. A modification of the Mustardé technique for the surgical repair of a large feline eyelid coloboma. Vet Ophthalmol. 2001 Jun;4(2):159-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11422999

Martin CL, Stiles J, Willis M. Feline colobomatous syndrome. Vet Comp Ophthalmol 1997; 7:39

Munger RJ, Gourley IM. Cross lid flap for repair of large upper eyelid defects. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1981 Jan 1;178(1):45-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7204222

Pavletic MM, Nafe LA, Confer AW. Mucocutaneous subdermal plexus flap from the lip for lower eyelid restoration in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1982 Apr 15;180(8):921-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7085469

Roberts SR, Bistner SI. Surgical correction of eyelid agenesis. Mod Vet Pract 1968; 49:40

Whittaker CJ, Wilkie DA, Simpson DJ, Deykin A, Smith JS, Robinson CL. Lip commissure to eyelid transposition for repair of feline eyelid agenesis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2010 May;13(3):173-8 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20500717

Wolfer JC. Correction of eyelid coloboma in four cats using subdermal collagen and a modified Stades technique. Vet Ophthalmol. 2002 Dec;5(4):269-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12445297