-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Martin Coster, DVM, MS, DACVO

Martin Coster, DVM, MS, DACVO

angell.org/eyes

ophthalmology@angell.org

617-541-5095

Introduction

Feline herpesvirus is a common cause of feline ocular disease worldwide.1,2 The ubiquitous nature of the virus is maintained due to its high infectivity of immunologically naïve kittens, and its ability to establish lifelong neuronal latency (in trigeminal ganglia) in recovered individuals. Reactivation and shedding of virus, both with and without clinical signs, occurs commonly.4 The virus is epitheliotropic, resulting in corneal and conjunctival epithelial ulceration, with ensuing inflammation. The morbidity of FHV-1 related disease is a major cause for shelter cats to be euthanized.5 Feline viral rhinotracheitis (FVR is an infectious disease caused by FHV) vaccination will diminish the severity and duration of disease outbreaks, but does not prevent disease.

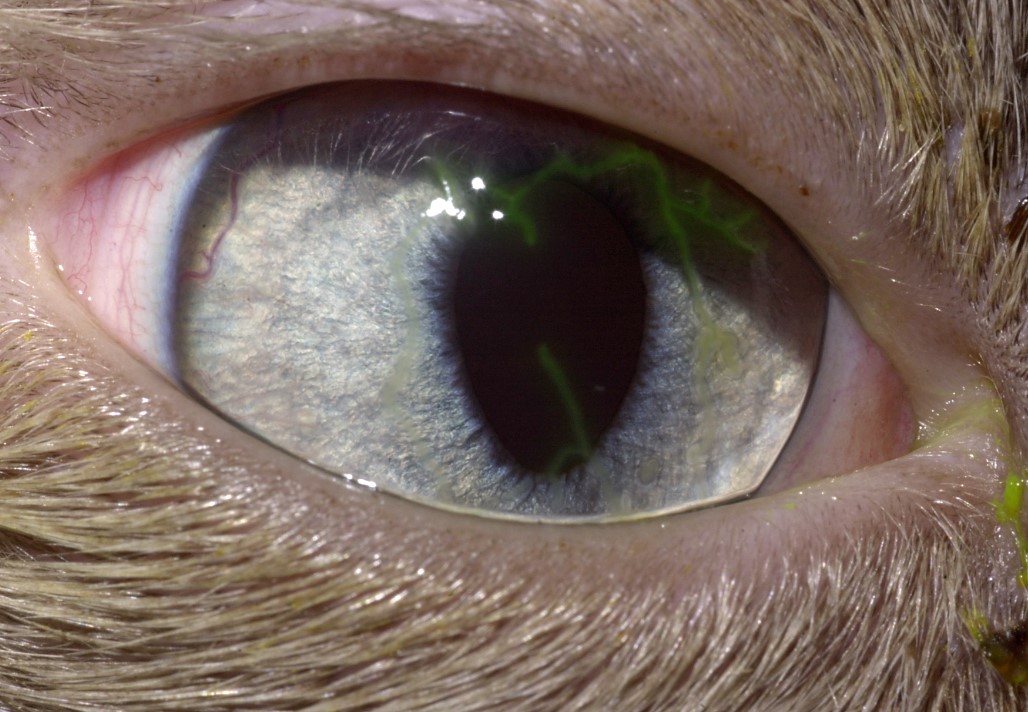

The clinical signs of ocular FHV are unilateral or bilateral conjunctival hyperemia and chemosis (Figures 1 and 2), blepharospasm and ocular pain, serous to mucoid ocular-nasal discharge, and superficial corneal ulceration that begins as linear (dendritic, Figure 3) or punctate lesions and quickly progresses to large areas of ulceration. Secondary bacterial keratitis can result in stromal loss, corneal malacia (“melting”), or even corneal perforation. Young cats are generally affected, although any cat may show recurrent symptoms that may be associated with stress. Differential diagnoses for feline herpesviral conjunctivitis include calcivirus, Chlamydophila felis, Mycoplasma spp, and allergic inflammation.

Unfortunately, there is no definitive diagnostic test to confirm FHV as the cause of specific clinical symptoms, and so most diagnoses are presumptive based on clinical signs or ruling out other differentials. Given a sensitive enough test, such as quantitatitive PCR, most cats would test positive regardless of their clinical state.6 PCR of conjunctival swabs can document Chlamydophila felis or Mycoplasma infection, or treatment with systemic doxycycline (10mg/kg PO q24h for 14 days) and/or topical oxytetracycline (Terramycin®, Zoetis) can aid in ruling these out. Corneal and/or conjunctival cytology will aid in evaluating for bacterial involvement, and potentially Chlamydophila inclusions may be seen in the first week of infection.

Cases of mild conjunctivitis in the immunocompetent cat are generally self-limiting, over the course of 2-3 weeks, and specific medical therapy may not be necessary beyond general supportive care and cleansing of discharge.

Moderate to severe conjunctivitis, and cases with concurrent corneal ulceration, will benefit from targeted antiviral therapy.

Figure 1: Feline herpesviral conjunctivitis, with mild chemosis and hyperemia. A differential diagnosis for conjunctivitis is Chlamydophila felis.

Figure 2: Severe feline herpesviral conjunctivitis. Note the conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, and third eyelid elevation (a sign of pain).

Topical Antiviral Agents

Topical antiviral therapy is important when the corneal surface is compromised, when herpetic conjunctivitis is moderate to severe, or when chronic or recurrent disease states are present. The choice of using a topical vs oral antiviral may depend on patient and client compliance factors (which dosage form and frequency is most acceptable to the cat and owner), the degree of infection present (e.g. herpesviral dermatitis and rhinotracheitis may benefit from an oral antiviral whereas limited corneoconjunctival disease may benefit from targeted local treatment, i.e. an eye drop), and cost. Available topical antivirals are 1% trifluridine (generic or Viroptic, Pfizer), compounded 0.2% idoxuridine, or compounded 0.5% cidofovir.7 Since these medications are virostatic, high frequency usage (q4-6h) is important, with the exception of cidofovir which has a long half-life and can thus be effective q12h (making it the author’s preferred therapy). It is important to note that antivirals such as cidofovir likely only limit the severity of clinical symptoms, not the duration of the disease cycle, which is typically around 3 weeks.7

Famciclovir

Oral famciclovir also has good effects against FHV,8 although the dosage required is still a matter of debate, with a range of 15 to 90 mg/kg PO q8-12h proposed. Historically, a single 40mg/kg dose was shown to be equivalent to 90mg/kg,9,10 but in a follow-up report, the median time to clinical improvement was significantly shorter, and the degree of improvement was significantly greater in cats receiving 90mg/kg q8h than in cats receiving 40mg/kg q8h.11 A dose of 62.5mg/cat once to twice a day has been separately advocated.12 A more recent report showed both 30mg/kg and 90 mg/kg q12h dosing to reduce conjunctival FHV shedding in a shelter population, although clinical symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections were not improved.13 Finally, in a study of famciclovir pharmacokinetics in 2016, a dosage of 90 mg/kg q12h was recommended to provide therapeutic levels in the tears.14

In this author’s experience, the “ideal” dose of famciclovir must be balanced with patient and client compliance (the motivation and ability to pill this large tablet to the average cat 2 to 3 times a day), the logistics of deriving doses from 250 or 500 mg tablets, and cost (the average cash price for twenty-one 500mg tablets, i.e. a one week course of q8h therapy, is over $100, although online discount sites can significantly reduce this). When using famciclovir, the author therefore generally aims for the average cat to receive 500mg q8h, but will often see response at dosing as low as 125mg q12h. Balancing patient and client compliance factors, most of the author’s cases successfully receive 250mg q12h (in an average-sized cat).

Antibiotics

In the more severe conjunctivitis cases or whenever the cornea is compromised, topical antibiotics are essential to help prevent secondary bacterial infection; oxytetracycline, erythromycin ointment, or tobramycin drops q8h are good first-line choices. The author avoids triple antibiotic products containing neomycin and polymyxin, due to concerns with anaphylaxis in the cat. However, oxytetracycline ointment (Terramycin®, Zoetis) also contains polymyxin B and has also been reported (less commonly) to have caused anaphylaxis in some cats. 24,25 Oral antibiotics are generally unnecessary for prophylaxis unless respiratory tract signs with fever, lethargy, and anorexia are also present, in which case doxycycline (5 mg/kg PO q12h, or 10 mg/kg PO q24h) is a good empiric choice for primary or secondary bacterial infections, as well as providing treatment in case of Chlamydophila felis infection.15 If bacterial ulcerative keratitis is present, therapy is markedly different and would require bacterial culture and sensitivity for the most appropriate antimicrobial therapy, that is beyond the scope of this monograph.

L-Lysine

L-Lysine, 500mg PO q12h in the adult cat or 250mg PO q12h in kittens, has been previously shown to reduce the severity, but not necessarily the length, of FHV outbreaks.16-19 However, further research showed an increase in viral shedding in shelter cats administered L-Lysine.20 In a review article, Bol & Bunnik,21 recommended “an immediate stop of lysine supplementation because of the complete lack of any scientific evidence for its efficacy.” The authors also discuss concerns about lysine antagonizing arginine and causing harm. However, this review casts aside positive results of Lysine on FHV clinical signs, and provides the unhelpful conclusion that “cats suffering from an active FHV-1 infection may be given extra palatable food and some extra love and attention”. The preeminent veterinary ophthalmologists currently studying FHV, Thomasy and Maggs, concluded in 2016 that “lysine is safe when orally administered to cats and, provided that it is administered as a bolus, may reduce viral shedding in latently infected cats and clinical signs in cats undergoing primary exposure to the virus”.22

Clinically, the author therefore still recommends L-lysine in any cat with herpes that will tolerate its administration; i.e. if the act of giving lysine creates further stress or inappetence for the cat, it may then be contraindicated. Client education about the controversy is also clearly important.

Anti-Inflammatory Therapy

For severe, protracted conjunctivitis that continues over 3 weeks in spite of antiviral therapy, topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (eg flurbiprofen) or cyclosporine may be helpful to dampen the immune response. These medications should be used extremely cautiously, with frequent monitoring (q5-7 days), and should not be used if corneal ulceration is present or develops. Topical steroids are contraindicated, and oral steroids can delay healing or increase the risk of severe secondary bacterial infections.

Pain Control

Pain management in the herpetic cat should include nursing care by cleansing ocular discharge, lubricating artificial tears ointments for conjunctival erosions, and oral pain medication (e.g. sublingual buprenorphine or oral gabapentin) as needed.

For pain control of ulcers accompanied by miosis and severe blepharospasm, topical atropine may be helpful, as a strong cycloplegic agent. The dose may be titrated to effect, based on the duration of mydriasis, and can be quickly tapered to effect (q8-12h down to q24-48h over a few days). When using atropine in cats, ointment is generally much better tolerated than drops, as ointment will slowly diffuse down the nasolacrimal duct instead of flooding their nose and mouth with this bitter tasticant, as a drop would. It is not uncommon for atropine to induce severe hypersalivation, and some cats develop light sensitivity secondary to dilation that can then make ongoing pain assessment more challenging.

Conclusions

The ubiquitous feline herpesvirus can be challenging to treat, but with targeted antiviral therapy along with prophylactic antibiotic therapy, supportive care, and appropriate management of pain and inflammation, success can be achieved.

References & Further Reading

- Maggs DJ. Conjunctiva In: Maggs DJ, Miller PE,Ofri R, eds. Slatter’s Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier, 2008;135-150.

- Stiles J. Feline herpesvirus. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2003;18:178-185.

- Whitley RD. Canine and feline primary ocular bacterial infections. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2000;30:1151-1167.

- Gaskell RM, Povey RC. Experimental induction of feline viral rhinotracheitis virus re-excretion in FVR-recovered cats. Vet Rec 1977;100:128-133.

- Pedersen NC, Sato R, Foley JE, et al. Common virus infections in cats, before and after being placed in shelters, with emphasis on feline enteric coronavirus. J Feline Med Surg 2004;6:83-88.

- Townsend WM, Stiles J, Guptill-Yoran L, et al. Development of a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay to detect feline herpesvirus-1 latency-associated transcripts in the trigeminal ganglia and corneas of cats that did not have clinical signs of ocular disease. Am J Vet Res 2004;65:314-319.

- Fontenelle JP, Powell CC, Veir JK, et al. Effect of topical ophthalmic application of cidofovir on experimentally induced primary ocular feline herpesvirus-1 infection in cats. Am J Vet Res 2008;69:289-293.

- Thomasy SM, Lim CC, Reilly CM, et al. Evaluation of orally administered famciclovir in cats experimentally infected with feline herpesvirus type-1. Am J Vet Res 2011;72:85-95.

- Thomasy SM, Maggs DJ, Moulin NK, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of penciclovir following oral administration of famciclovir to cats. Am J Vet Res 2007;68:1252-1258.

- Thomasy SM, Whittem T, Bales JL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of penciclovir in healthy cats following oral administration of famciclovir or intravenous infusion of penciclovir. Am J Vet Res 2012;73:1092-1099.

- Thomasy SM, Shull O, Outerbridge CA, et al. Oral administration of famciclovir for treatment of spontaneous ocular, respiratory, or dermatologic disease attributed to feline herpesvirus type 1: 59 cases (2006-2013). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2016;249:526-538.

- Malik R, Lessels NS, Webb S, et al. Treatment of feline herpesvirus-1 associated disease in cats with famciclovir and related drugs. J Feline Med Surg 2009;11:40-48.

- Cooper AE, Thomasy SM, Drazenovich TL, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic effects of twice-daily famciclovir administration on infectious upper respiratory disease in shelter-housed cats. J Feline Med Surg 2018:1098612X18789719.

- Sebbag L, Thomasy SM, Woodward AP, et al. Pharmacokinetic modeling of penciclovir and BRL42359 in the plasma and tears of healthy cats to optimize dosage recommendations for oral administration of famciclovir. Am J Vet Res 2016;77:833-845.

- Lappin MR, Blondeau J, Boothe D, et al. Antimicrobial use Guidelines for Treatment of Respiratory Tract Disease in Dogs and Cats: Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases. J Vet Intern Med 2017;31:279-294.

- Maggs DJ, Collins BK, Thorne JG, et al. Effects of L-lysine and L-arginine on in vitro replication of feline herpesvirus type-1. Am J Vet Res 2000;61:1474-1478.

- Maggs DJ, Nasisse MP, Kass PH. Efficacy of oral supplementation with L-lysine in cats latently infected with feline herpesvirus. Am J Vet Res 2003;64:37-42.

- Fascetti AJ, Maggs DJ, Kanchuk ML, et al. Excess dietary lysine does not cause lysine-arginine antagonism in adult cats. J Nutr 2004;134:2042S-2045S.

- Stiles J, Townsend WM, Rogers QR, et al. Effect of oral administration of L-lysine on conjunctivitis caused by feline herpesvirus in cats. Am J Vet Res 2002;63:99-103.

- Drazenovich TL, Fascetti AJ, Westermeyer HD, et al. Effects of dietary lysine supplementation on upper respiratory and ocular disease and detection of infectious organisms in cats within an animal shelter. Am J Vet Res 2009;70:1391-1400.

- Bol S, Bunnik EM. Lysine supplementation is not effective for the prevention or treatment of feline herpesvirus 1 infection in cats: a systematic review. BMC Vet Res 2015;11:284.

- Thomasy SM, Maggs DJ. A review of antiviral drugs and other compounds with activity against feline herpesvirus type 1. Vet Ophthalmol 2016;19 Suppl 1:119-130.

- Sykes JE. Feline chlamydiosis. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2005;20:129-134.

- Plunkett S. Anaphylaxis to ophthalmic medication in a cat. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2000;10:169-171.

- Hume-Smith KM, Groth AD, Rishniw M, et al. Anaphylactic events observed within 4 h of ocular application of an antibiotic-containing ophthalmic preparation: 61 cats (1993-2010). J Feline Med Surg 2011;13:744-751.