-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Emergency/Critical Care Service

Angell Animal Medical Center

617-522-7282

Obstipation is the term applied when constipation (incomplete defecating) is so severe that the stool can no longer be passed. Stool then accumulates in the colon becoming more and more voluminous as the patient eats, and getting harder and harder as the large bowel absorbs more and more water from the mass of stool. Feline idiopathic megacolon is the most common cause of obstipation in the cat. Some other causes of obstipation include pelvic deformity from trauma, neoplasia, strictures, foreign bodies, and cauda equina syndrome. Feline megacolon is most commonly seen in middle aged male cats, and any breed can be affected. It is the result of dysfunction of the colonic smooth muscle. Most obstipated cats strain to defecate and produce little or no stool. If obstipation is severe, it can result in vomiting, and even diarrhea due the irritation that the hard stool causes against the colonic wall. This is unfortunately a slowly progressive disease, and the ability to defecate usually worsens over months and years.1

Medical Management

In the development of feline megacolon, medical and dietary management can be successful in delaying the need for deobstipation. The colon still maintains some ability to contract and expel stool, but defecation may be infrequent or incomplete (constipation). If management efforts lapse, obstipation may result.

Dietary management is often a first line choice to manage developing feline megacolon. Higher fiber diets can be useful at this stage of management. Soluble fiber is preferable to insoluble fiber foods, since insoluble fiber tends to be bulk forming and further distend the colon. Soluble fiber is highly fermentable, attracts water into the stool, and aids in gel formation within the colon. The soluble vs insoluble fiber fraction usually does not appear on pet food labels, rather crude fiber is listed which is a measure of both soluble and insoluble fiber.2 As colon function declines and obstipation develops, low residue diets can help to decrease stool volume.

Prokinetic medications may be successful in early management. Cisapride is often the prokinetic of choice. It has been shown to improve smooth muscle cell contraction in vitro, but the in vivo benefits of this medication for feline idiopathic megacolon are unproven. Nonetheless, it remains a rational and anecdotally supported medication to use. The starting dose is 2.5 mg BID, but can be titrated upwards as needed to 5-7.5 mg TID. Cisapride is no longer available for human use due to its arrhythmogenicity, but it can be gotten from compounding pharmacies for veterinary use. Other prokinetics that may be considered include ranitidine, misoprostol, and metoclopramide, but they are likely not as effective as cisapride.1

Stool softeners are also a common first line choice for any cat that is having difficulty defecating. Lactulose (0.5 ml/kg BID-TID)3, has historically been the laxative of choice. The dose of this medication may be adjusted by the owner to achieve a desired stool consistency. It is an indigestible sugar that osmotically pulls water in to the bowel. It can sometimes be difficult to give to cats due to the flavor and mouth feel, limiting client compliance. MiraLax™ (polyethylene glycol 3350) may be replacing lactulose as the stool softener of choice for cats with megacolon and obstipation. It has virtually no flavor and can be easily sprinkled on or mixed with wet food. The starting dose is 1/8 to ¼ teaspoon BID, and this dose is titrated upwards depending on desired stool consistency. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 is not absorbed from the intestinal tract and binds to as many as 100 water molecules resulting in a softer stool. It was shown to mildly increase potassium levels and may result in some dehydration if a patient does not drink adequately. High doses can result in diarrhea – like any laxative.4

Almost invariably, medical management will eventually fail as the colon loses more and more contractibility. If the stool becomes too hard and too wide to pass thru the pelvic outlet (see image 1), some method of deobstipation may be necessary.

Enemas

Enemas can be successful if the stool is not yet too firm or too voluminous. Enemas of about 60 ml per cat can be used and may need to be repeated every 8 hours. Enema solutions of warm water, saline, or water mixed with a water based lubricant or lactulose have been used. I find the mixture of 50 ml of warm water with 5-10 ml of water based lubricant well tolerated and much easier to clean up than an enema containing lactulose or other lubricants.

Manual Deobstipation

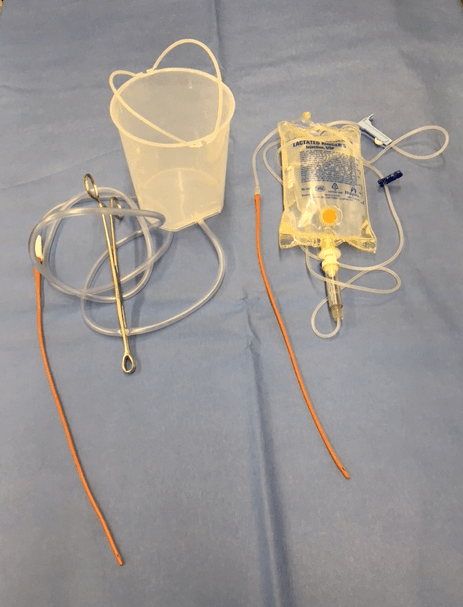

If the stool volume is simply too much to mobilize with enemas, then manual deobstipation is an option. The patient should be anesthetized and intubated. A pre-procedure radiograph of the abdomen to show stool volume and pelvic conformation may be helpful but is not necessary. Pelvic narrowing can usually be detected by rectal palpation of the pelvis. It is helpful to have a 1 liter bucket of warm water hung above the patient which is connected to an 8 or 12 French red rubber catheter via a segment of suction tubing (see image 2), or a bag of warmed IV fluid with tubing can be used. The tube can then be clamped off using a Kelly hemostat or Carmalt to control flow. Using a gloved finger covered with ample water based lubricant, small pieces of the stool can be chiseled off the distal end of the stool mass per rectum. Those pieces of stool need to be small enough that they can be removed via the rectum, often pressed between the gloved finger and the pelvic brim. Using forceps of any sort for this procedure should generally be avoided due to the risk of colonic damage and perforation. Once the stool mass is no longer reachable per rectum, the red rubber catheter (covered in water based lubricant) should be inserted rectally and about 50 ml of warm water can be infused. It helps to insert the red rubber catheter quite deeply so the tip is positioned oral to the stool mass. As the water then flows out the rectum, the stool mass is brought aborally. Some gentle pressure on the cranial abdomen pushing the stool mass caudally is helpful to bring the stool back into reach. This process is repeated about 10-20 times until no more stool is palpable in the abdomen. Once all the stool is successfully removed, the water that is flushed into the rectum will come out clear without any feces dissolved in it. This is generally a reliable indicator that no more stool remains. A post-procedure lateral radiograph may be helpful to confirm complete removal of the stool if this cannot be done by palpation. It is important to remember that anytime a gloved finger or red rubber catheter is inserted into the rectum that it be covered in water based lubricant to prevent abrasion and trauma to the rectal mucosa.

Medical Deobstipation

Medical deobstipation using a continuous infusion of polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350 (Colyte™ or Golytely™) solution via a nasogastric tube has largely supplanted the need for manual deobstipation. Even cats with very large volumes of stool can be successfully evacuated using this protocol with a 12-24 hour infusion. A nasogastric or nasoesophageal tube should be placed. Light sedation or topical analgesia is sometimes needed for tube placement. A post-placement radiograph should be taken to confirm appropriate placement and location of the tube. Via the nasogastric tube, a solution of PEG 3350 diluted according to the bottle instructions is infused at 6-10 ml/kg/hr. This dilution of the PEG 3350 does not result in fluid shifts either into or out of the cat, so neither over hydration, dehydration nor significant electrolyte derangements are expected. In a small pilot study of 9 constipated cats by Dr. Anthony Carr, the median time to significant defecation was 8 hours (range 5 to 24 hours), and the median total dose given was 80 ml/kg (range 40-156 ml/kg).6 It is admittedly hard to imagine that this method can successfully evacuate such large volumes of stool like in image 1, but we have been pleasantly surprised with both the effectiveness and rapidity of this method. It seems well tolerated by the patient and avoids general anesthesia.

For more information, please contact Angell’s Emergency Service at 617-522-7282 or emergency@angell.org.

References

- CG Byers, CS Leasure, NA Sanders. Feline Idiopathic megacolon, Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 28(9): 658-665, 2006

- M Chandler. Focus on Nutrition: Dietary Management of Gastrointestinal Disease, Compend Contin Educ Prac Vet 35(6): E1-E3, 2013

- Plumb’s Veterinary Drug Handbook. Ed. DC Plumb. 8th Edition, 2015

- FM tam, AP Carr, SL Myers. Safety and Palatability of Polylethylene Glycol 3350 as an Oral Laxative in Cats, J Feline Med Surg 13: 694-697, 2011

- DCA Candy, D Edwards, M Geraint. Treatment of Fecal Impaction with Polyethylene Glycol Plus

Electrolytes (PGE + E) Followed by a Double-blind Comparison of PEG + E Versus Lactulose as Maintenance. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 43(1): 65-70, 2006 - AP Carr, MC Gaunt (2010). Constipation Resolution with Administration of Polyethylene-Glycol Solution in Cats (Abstract). Proceedings: ACVIM. accessed via Veterinary Information Network; vin.com