-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Steven Tsai, DVM, DACVR

By Steven Tsai, DVM, DACVR

angell.org/diagnosticimaging

diagnosticimaging@angell.org

617-541-5139

Vomiting and inappetence are very common presenting complaints both to veterinary general practitioners and to veterinary emergency centers. They are unfortunately also exceedingly nonspecific findings, with potential causes running the gamut from self-limiting gastroenteritis to neoplasia to life-threatening gastrointestinal rupture. Abdominal imaging will almost always be part of the recommended diagnostic work-up, with abdominal radiographs being the most common initial study. Interpreting abdominal radiographs is sometimes more art than science, with few (if any) reliable rules to differentiate gastrointestinal obstruction from nonobstructive conditions. This article aims to be quite narrow in scope, presenting my own approach to determining whether there is evidence of small intestinal mechanical obstruction on plain radiographs. This article will not cover general causes of vomiting, small intestinal plication (linear foreign bodies), or pyloric outflow obstructions (generally identical in appearance to functional gastric ileus).

One of the more common misconceptions is that something meaningful can be concluded from the presence, amount, or character of gas in the small intestines. Aerophagia commonly occurs both during respiratory activity and during normal eating. A large portion of the gas enters the small intestinal tract and is visible on normal radiographs. Gas is also formed by the colonic microflora, some of which may reflux into the distal small intestines. Gas may admix with ingesta/chyme, creating small gas bubbles focally or diffusely through the intestines. The amount and appearance of gas in the intestines is simply not a sign of mechanical obstruction.

When evaluating abdominal radiographs for signs of obstruction, the only thing I am looking for is segmental dilation of the small intestines. While gas in an intestinal segment may help to define its diameter, the only thing that matters is the diameter and not the composition of its contents. When assessing for segmental dilation, there are three basic steps:

- Identify the colon

- Identify small intestines with greater than normal diameter

- Identify small intestines with normal diameter

Without first identifying the colon, one may fall into the trap of thinking the colon (especially the ascending or transverse segments) represents markedly gas-dilated small intestines. If the colon is not clearly visible or identifiable, one can perform a pneumocolon to definitively locate it. More information on pneumocolon can be found here: angell.org/angell_services/pneumocolon.

Once the colon has been identified and can be excluded from consideration, the next step is to identify one or more small intestinal segments which are abnormally dilated. This is where the art comes in, as a reliable and universally accepted definition of normal generally does not exist. The most commonly cited measurement is a multiple of 1.6 times the height of the L5 vertebral body on a lateral radiograph.1 In the original study establishing this criterion, the threshold of 1.6 was chosen for high sensitivity, with 86% of obstructed dogs having a value higher than 1.6x L5. The specificity of this threshold was quite low, however, with only 50% of dogs with a value higher than 1.6x L5 actually being obstructed. A more recent study revisited the topic of intestinal measurements and established that dogs with a maximum small intestinal diameter less than 1.4x L5 were very unlikely to be obstructed, while those greater than 2.4x L5 were very likely to be obstructed.2 Dogs with values between 1.4x and 2.4x warranted further investigation. With cats, a value of 12mm as the maximum normal diameter of the small intestines is commonly used. This threshold is also more likely to be a set point for a grey area rather than a reliable cutoff to use.

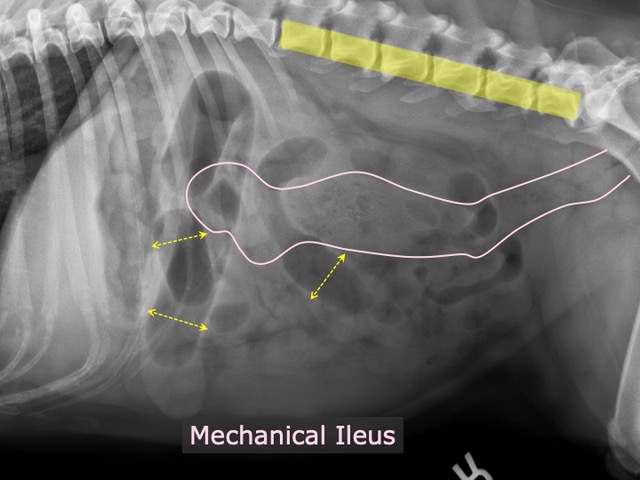

Figure 1 – Lateral radiograph in a dog with confirmed small intestinal obstruction. The colon is outlined in pink. Thick yellow stripe overlying the lumbar vertebrae establishing approximate normal small intestinal diameter. Several small intestinal segments (yellow arrows) with diameter significantly greater than normal. Remaining small intestinal segments are normal in diameter.

The third step in determining segmental dilation is to find a population of normal small intestines, thus satisfying the traditional “two populations of bowel” rule. It is not simply enough to find some intestines with a diameter of, say 1.7x L5 with others being 1.5x L5. These are of course just expected deviations within the grey area. Traditionally, it is thought that no small intestinal segment should be more than twice the diameter of any other segment. The more recent study also found that patients with a maximum small intestinal diameter less than 2x the minimum diameter were unlikely to be obstructed. Those with a maximum diameter greater than 3.4x the minimum diameter were likely to be obstructed.2

While studies and numbers and cutoff values are all well and good, in practice it is quite rare for me (and likely most radiologists) to be measuring structures and basing our decisions on strict cutoff values. My general approach is first to identify the colon. Second, I look at the entire lumbar vertebral column and use the approximate height of the vertebral endplates as my mental set point for normal intestinal diameter. I then look for any small intestines, whether fluid filled or gas filled, which are larger than the vertebral bodies. If any are present, I then look for any other small intestines that are less than half the diameter of the dilated segment. (Figure 1) If any of these criteria are lacking, I will generally conclude the patient is unlikely to be obstructed. If the criteria are present and far past the cutoff values (e.g., over twice the vertebral body height and more than three times the minimum diameter) I will recommend surgery. And if the criteria are met but are in the grey area, I recommend ultrasound.

References

- Graham JP, Lord PF, Harrison JM. Quantitative estimation of intestinal dilation as a predictor of obstruction in the dog. J Small Anim Pract1998;39:521–524.

- Fink C et al. Radiographic diagnosis of mechanical obstruction in dogs based on relative small intestinal external diameters. Vet Radiol Ultrasound2014;55:472-479.