-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Michael M. Pavletic, DVM, DACVS

Michael M. Pavletic, DVM, DACVS![]()

Director of Surgery

angell.org/surgery

surgery@angell.org

617-541-5048

Preoperative Assessment of the Surgical Patient

Every veterinarian performing basic skin surgery occasionally encounters a problematic incisional closure due to significant skin tension. Unless this potential complication is assessed prior to surgery, the surgeon may find this intraoperative problem daunting.

Prior to surgery, manually assessing the regional skin’s natural or inherent elasticity will give the veterinary surgeon an idea of which area(s) of adjacent elastic skin can be recruited to close the surgical defect.

Example: From my clinical experience, the caudal-lateral thigh region is prone to dehiscence when the surgeon does not properly assess the skin tension prior to surgery. In this region, skin tension is best assessed with the dog standing on the rear legs. When standing, the muscles contract and exert tension to the overlying skin. In contrast, when the patient is under anesthesia, the muscles relax in this area and the skin may appear deceptively pliable and elastic. If a tumor is removed from this area, the wound closure may appear fine, only to be subject to significantly greater incisional tension when the patient is ambulatory postoperatively. For more challenging defects in this area, a transposition flap can effectively close the surgical defect and eliminate the risk of postoperative incisional dehiscence. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1A (left). Postoperative dehiscence in the caudal-lateral aspect of the left hind limb. Preoperatively, the veterinarian failed to assess proper skin tension with the dog standing. This resulted in closing the incision without taking into account the stretching force exerted by the underlying musculature when the dog is standing and walking. Figure 1B (right). This wound required time to heal by second intention. Note the skin staples used to close the incision. It is the author’s experience to avoid the use of skin staples to close incisions under tension. There is a risk that the staples will deform and open when subject to prolonged incisional tension. Had the tension been better assessed prior to surgery, a small transpositional flap would have been an effective option to close this surgical wound.

Ability to flex and extend the limb intraoperatively better allows for assessment of skin tension during wound closure. For example, the lateral flank area, cranial to the thigh, is an area subject to stretch forces as the patient extends its rear leg during ambulation. By anticipating this risk prior to surgery, the veterinarian is better prepared to consider various closure options to reduce incisional tension.

Preoperative assessment also will allow the surgeon to select the size of the area that will require clipping of fur and preparation for surgery. If a large area of skin is to be excised, a wider clip will provide the surgeon with greater latitude to recruit additional skin in the form of a skin flap if needed.

Figure 2. In large dogs, the skin is compressed against the surgical table, restricting the ability of the surgeon to close the large wounds illustrated. Sand bags or rolled cloth towels are used to elevate the weight of the dog’s trunk off the surgical table, facilitating the closure of these respective skin defects. (From Pavletic MM. Tension Relieving Techniques. In: Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery, 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2018; 286-7, with permission.)

Example: In a chain mastectomy, veterinarians may underestimate the degree of skin preparation necessary for this procedure. Following resection, closure will require the advancement of the lateral skin of the trunk. Preparation of the skin must include clipping of the fur at the mid-thoracic and abdominal area.

The inherent elasticity of the skin can vary considerably between individual dogs and cats. The skin’s inherent elasticity and skin thickness also varies in different body regions. The author has seen multiple cases in which a defect in one patient required a skin flap for closure whereas a similar wound in another patient was closed by basic skin undermining and advancement. Again, careful assessment of the skin prior to surgery can help avoid the need to address excessive incisional tension during closure of the cutaneous defect.

Options to Reduce Incisional Tension Intraoperatively

1. In large dogs, consider the placement of sandbags or rolled towels beneath the shoulders and pelvis to raise the trunk off the surgical table. This improves the mobility of the trunk skin by freeing the skin otherwise compressed or “trapped” against the table surface by the body weight of the patient. As a result, the veterinarian can more effectively mobilize this source of elastic skin to close challenging skin wounds of the trunk. (See Figure 2)

2. When dealing with cutaneous defects in the inguinal and ventral pelvic area, loosening the tape or strap stirrups applied to the rear legs can facilitate skin closure, allowing the surgeon to adduct the limbs.

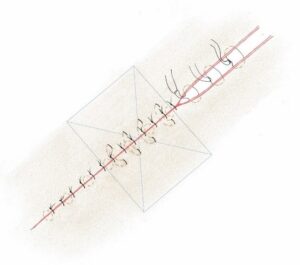

3. Intraoperatively, skin hooks can be used to stretch the incisional margins (“Load Cycling”) in order to gain a few centimeters of skin, reducing incisional tension. For example, stretching the skin for 30-60 seconds followed by 30 seconds of relaxation is repeated over a 5-10 minute period. In so doing, 1-3 centimeters may be gained to facilitate closure. The net gain depends on the area of the body and the regional elastic properties of the patient’s skin. (See Figure 3)

4. Undermining is one of the first surgical options employed to mobilize skin intraoperatively. It can be performed in relative safety if the surgeon keeps in mind the need to protect the regional cutaneous circulation.

a. Undermine the skin safely below the dermis to avoid trauma to the deep or subdermal plexus.

b. Undermine beneath the panniculus muscle layer, where present, to help preserve circulation to the overlying skin

Figure 3. Intraoperative stretching of the skin using moderate force using skin hooks. The skin is stretched and relaxed in a cyclic fashion [30-60 seconds of tension followed by 30 seconds relaxation] over a 5-10 minute period. This is repeated on the opposing cutaneous margin.

c. Minimize damaging or ligating regional direct cutaneous vessels. Extensive undermining can be safely performed if these major cutaneous vessels are preserved.

5. “Skin Directing” is a term I use to describe the manual shifting of the skin surrounding a cutaneous defect in order to see how best to direct the loose, more elastic skin to the closure area under greatest tension. [In more challenging closures, simple linear edge-to-edge apposition may result in greater incisional tension compared to shifting the skin. The result usually is a sigmoid shaped closure, reducing incisional tension.] (See Figure 4)

6. “Angular closure” can be useful for closing some problematic skin defects of the upper tail and extremities, instead of closing a wound in a proximal-distal direction or perpendicular to the axis of the tail/limb. With closure of the incision at a diagonal to these axes, tension is distributed in an angular or spiral fashion while helping to avoid circumferential tension. (See Figure 5)

7. Never close extremity wounds and surgical defects under circumferential tension in order to avoid creating a biologic tourniquet. Unless detected early, biologic tourniquets impair lower extremity circulation which can result in extensive tissue swelling and necrosis. Simply leaving the wound partially open to heal by 2nd intention may be your best option.

Figure 4A (left). Wide resection of a fibrosarcoma involving the right lateral thigh of a cat. Figure 4B (right). The more elastic skin of the cranial thigh region was undermined and “directed” to the widest central area of the defect. This shifting of skin resulted in less tension when compared to closing the defect in a direct linear fashion. (From Pavletic MM. Tension Relieving Techniques. In: Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery, 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2018; 276, with permission.)

8. If additional tension relief is needed, consider the use of small, 1cm staggered incisional release incisions especially in the zone of greatest incisional tension. (See Figure 6)

9. Other techniques to consider include the use of Z-Plasty to reduce incisional tension and the use of “Walking Sutures” to help advance or “Walk” the undermined skin toward the opposing skin border. Details of their use are in the author’s Atlas. Although both methods can be useful in facilitating closure, the author normally prefers the other options presented in this article.

Figure 5A (left). Angular or spiral closure technique. This cutaneous adenoma of the upper tail is resected. Figure 5B (middle). Following resection, closure in a proximal-distal direction or laterally would result in moderate skin tension in these two planes, risking dehiscence. Lateral closure also could result in creating a biologic tourniquet from excessive circumferential skin tension. Figure 5C (right). Closure at an angle or in a spiral fashion distributes tension in a more uniform fashion. Note three placed vertical mattress sutures were used to reduce incision tension in the central area of the closure. (From Pavletic MM. Tension Relieving Techniques. In: Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery, 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2018; 277, with permission.)

10. If tension remains as a concern after closure, skin stretchers can be used for a few days postoperatively to remove skin tension which is normally in the central area of the incisional closure. (See Figures 7A-7D)

Figure 6. To further reduce circumferential skin tension after resection of a tail mass, mini-release incisions were used to reduce incisional tension (From Pavletic MM. Tension Relieving Techniques. In: Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery, 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2018; 268, with permission.) Following creation of the incisions, perpendicular to the line of tension, the mini-release incision may close (partially or completely) in the opposite direction. Any gaps will heal by second intention healing.

Closure Options to Reduce the Risk of Dehiscence

Figure 8 is an illustration from my referenced Atlas. This layered closure technique is highly effective in reducing the risk of dehiscence in areas where a mild amount of incisional tension persists. You will note that interrupted intradermal sutures are useful in distributing skin tension while serving as a “safety or backup layer” of sutures to the external skin sutures. Note the zone of greatest tension is often the central third of the closure, which usually corresponds to the widest portion of the wound. Interrupted skin sutures are used to closely approximate the incisional margins. In the central zone of tension, vertical mattress sutures are used to further protect the incision from wound dehiscence. [As noted, skin stretcher pads and cables can be applied postoperatively to further reduce incisional tension.]

Figure 7A (upper left). Sarcoma involving the right lateral thigh of a dog; Figure 7B (upper right). Wide resection of the fibrosarcoma. The skin was undermined and stretched intraoperatively with skin hooks; Figure 7C (lower left). Skin stretcher pads, comprised of a Velcro pad and adhesive membrane, were applied with surgical cyanoacrylate glue. Note the pads were placed cranial and caudal to the central area of the incision, where the greatest incisional tension was noted. See Figure 8 regarding the most effective suture pattern combination to consider for incisional closures under tension. Figure 7D (lower right). Application of the skin stretcher cable after placement of a protective cotton pad over the incision. The mild elastic force of the cable draws the skin pads towards the incision, further deceasing incisional tension postoperatively. (From Pavletic MM. Tension Relieving Techniques. In: Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery, 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2018; 279, with permission.)

Figure 8 (above). The author’s favorite combination of sutures patterns is illustrated to close wounds under mild to moderate skin tension. (As noted, closure should not create circumferential tension that could compromise circulation to an extremity.) Buried intradermal sutures are used to align incisional borders. This is followed by external interrupted skin sutures to accurately align cutaneous borders. Incisional tension is normally greatest in the central area of wound closure, as denoted in the “x-box” area. In this “central zone,” vertical mattress skin sutures are applied to further reduce the risk of dehiscence. Average thickness skin is normally aligned with 3-0 intradermal suture material; external sutures are normally 3-0 sized simple interrupted sutures. In thick skin, 2-0 sized sutures are used for intradermal sutures: 2-0 sized sutures can be used to approximate the skin in a simple interrupted suture pattern. In most cases, 2-0 suture material is used for vertical mattress sutures. Surgical glue also can be applied over the incision to seal its surface and give additional security. (Surgical glue has the general suture holding strength of 5-0 suture material.) (From Pavletic MM. Tension Relieving Techniques. In: Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery, 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2018; 278, with permission.)

Reference

Pavletic MM. Atlas of Small Animal Wound Management and Reconstructive Surgery, 4th ed. Wiley Blackwell, 2018.