-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Kiko Bracker, DVM, DACVECC

Kiko Bracker, DVM, DACVECC

www.angell.org/emergency

617-522-7282

Leptospirosis is a bacterially caused disease that commonly affects the kidney and the liver. The causative organism is motile spirochete (Leptospira) that can affect a wide array of mammals including dogs, humans, rarely cats, and a range of wildlife. Although there are well over 100 pathogenic serovars of Leptospirosis that are adapted to different hosts1,2, the most commonly identified serovars found in the United States include Icterohemorrhagiae, Canicola, Pamona, Bratislava, Grippotyphosa and Hardjo. Leptospires are shed in the urine of infected individuals, and the bacterium can persist in the environment in moist areas of limited sunshine. Infection occurs when the oral, ocular, or nasal mucous membranes of susceptible animals contact the bacteria in free standing water, vegetation, urine-contaminated soil or other similar settings. Infection likely can also be spread by direct contact with infected individuals through grooming, fighting, or consumption. Since urbanized wildlife (raccoons, skunks, coyotes, rodents, etc…) may carry and shed leptospirosis, even animals that do not venture into more rural settings should be considered potentially at risk. The late summer and early fall show a spike in leptospirosis cases nationwide, but it can be seen year-round and it tends to be more prevalent in warmer, wetter climates. Hawaii has the most human cases in the United States.1

Prevention

A tetravalent vaccination for leptospirosis is available in North America that includes the serovars Icterohemorrhagiae, Canicola, Pamona, and Grippotyphosa. Immunity lasts for at least 12 months. Vaccination breaks allowing vaccinated dogs to develop naturally occurring infections are not well documented. If clinical disease does develop despite vaccination, then it likely would be mild.2 There has been some anecdotal concern that the leptospirosis vaccine results in a greater frequency of anaphylactoid reaction among small breed dogs. A larger study of vaccine reactions from 2005 did not show a greater risk with this vaccine.3 Some owners may elect not to vaccinate their dogs for leptospirosis since they are not considered ‘at risk’. The routine vaccination of all dogs, though, is generally recommended. We have seen clinical leptospirosis in small breed dogs coming from an urban/suburban setting, suggesting that our assessment of what ‘at risk’ means may need updating.

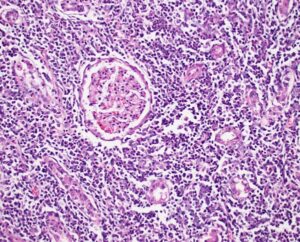

Photomicrograph of canine kidney with leptospirosis. Numerous leukocytes infiltrate the interstitium, separating and sometimes effacing renal tubules. This pattern is compatible with tubulointerstitial nephritis. An intact glomerulus is identified at the center of the image.

Diagnosis

Leptospirosis can prove to be a diagnostic frustration. The most common diagnostic test is the microscopic agglutination test or MAT that is commonly referred to as ‘lepto titers’. MAT results are often negative during the first week of illness.1 This test can take 7 days for a final result and it is significantly affected by prior vaccination with vaccine induced titers which are usually less than or equal to 1:800, but up to 1:3200 can be seen 2-4 weeks post vaccination.4 Titers of greater or equal to 1:800 or a fourfold titer increase in 2-4 week convalescent titers often suggest infection.8 Clearly there is some significant overlap between vaccine induced titers and infection titers. Generally, it has been thought that the highest serovar titer reflects the serovar of infection, but that is only true in about 50% of cases (human data).5 The absence of a convincing serologic diagnosis should not prevent appropriate treatment if the clinical picture strongly supports a diagnosis of leptospirosis.

Paired PCR tests of urine and blood are gaining popularity as a reliable and expeditious way to confidently arrive at a diagnosis of leptospirosis. Samples must be collected before any antibiotic is given or false negative results can occur. False negatives can also result if organisms are in too low a concentration.

We commonly submit both Leptospirosis titers (MAT) and PCR since the PCR is the more specific test and MAT is more sensitive.

Illness

The typical clinical picture of leptospirosis is that of acute renal and hepatic dysfunction, but renal or liver failure may also occur alone. Azotemia is noted in 80-90% of dogs with leptospirosis.1 ALP and bilirubin elevations are the most common hepatic analytes to be affected.1 Respiratory dysfunction is also relatively common and was noted in 70% of dogs in one study, and has been found in 9-93% of dogs in other studies.6 Thrombocytopenia was present in 73% of patients in the same study.6 Most dogs do not present with signs attributable to the urinary tract but instead have complaints of lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, painful abdomen. A diagnosis of leptospirosis is rarely suspected based on physical exam and history alone, and clinicopathologic data is generally needed to create that suspicion.

Treatment

The preferred treatment for leptospirosis is Doxycycline 5mg/kg PO/IV twice daily for 2 weeks. 1 Doxycycline eliminates the organism from the renal tubular cells. Penicillin drugs including Amoxicillin and Ampicillin are also effective against leptospires. If it is not possible to give doxycycline, then Ampicillin 20mg IV QID is used as a common alternative. Ampicillin should not be used orally due to poor bioavailability by that route. Other symptomatic therapies (antiemetics, H2-blockers, proton pump inhibitors, appetite stimulants) are used on an as-needed basis.

Fluid therapy can be a great challenge for patients with Leptospirosis. Oliguric or anuric renal failure is common and can be a life-threatening development for many of these patients. A fluid therapy algorithm is outlined below.

- Fluid deficit (dehydration) should be replaced over 12-24 hours.

- Maintenance fluid needs are usually supplied with a balanced crystalloid like LRS or Normosol-R.

- Urine output should be quantified by use of a urinary catheter. This also prevents exposure of veterinary personnel and other animals to potentially infectious urine. Once the patient is rehydrated, IV fluid input should roughly match urine output. If urine output lags behind IV fluid input and the patient is gaining weight, this is a sign of oliguria and the IV fluid rate should be slowed down to better match urine output.

- Conversion of oliguric (or even anuric) renal failure to polyuric renal failure can be facilitated by the use of IV diltiazem at a rate of 1-5 mcg/kg/min.7 We have had very positive experiences using Fenoldopam (an analog of dopamine) at 0.8mcg/kg/min.

- Although the diuretic furosemide is often used with oliguric or anuric renal failure to manage volume overload, it does not hasten improvement in renal function.

- If medical management of oliguric/anuric renal failure is not successful, then hemodialysis has proven to be a very effective way to manage these patients until their renal function improves (2-4 weeks).

Most patients with leptospirosis require hospitalization for 7 days or more. Many of them also need to have nasogastric or esophageal feeding tubes place due to reluctance to eat during the period of clinical illness.

Prognosis

The prognosis for dogs treated promptly and aggressively for leptospirosis is favorable (80% survival rate).1 Anuric dogs not responding to medical management require hemodialysis to survive. Dogs that develop respiratory complications have a survival rate closer to 40%.6

For more information, please contact Dr. Bracker at emergency@angell.org or kbracker@angell.org, or call 617-522-7282.

References

- JE Sykes, K Hartmann, KF Lunn, GE Moore, RA Stoddard, RE Goldstein. 2010 ACVIM small animal consensus statement on leptospirosis: diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment, and prevention. J Vet Intern Med. 25(1);Jan-Feb 2011:1-13

- Andre-Fontaine. Diagnosis algorithm for leptospirosis in dogs: disease and vaccination effects on the serological results. Vet Rec. May 2013;172(19):502

- GE Moore, LF Guptill, MP ward. Adverse events diagnosed within three days of vaccine administration in dogs. JAVMA. 227;2005:1102-1108

- SC Barr, PL McDonough, RL Scipioni-Ball, JK Starr. Serologic response of dogs given a commercial vaccine against serovar Grippotyphosa. Am J Vet Res. 66;2005:1780-1784

- PN Levett. Usefulness of serologic analysis as a predictor of the infecting serovar in patients with severe leptospirosis. Clin Infect Dis. 36;2003:447-452.

- B Kohn, et al. Pulmonary abnormalities in dogs with leptospirosis. J Vet Intern Med. 24;2010:1277-1282

- KA Mathews, G Monteith. Evaluation of adding diltiazem therapy to standard treatment of acute renal failure caused by leptospirosis: 18 dogs (1998–2001). Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. 17(2);2007:149–158

- Leptospira Serology, P Ewing. Clinical Veterinary Advisor: Dog and Cats, 3rd, Elsevier. 2015