-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Maureen C. Carroll, DVM, DACVIM and Megan Reilly, BS

By Maureen C. Carroll, DVM, DACVIM and Megan Reilly, BS![]()

angell.org/internalmedicine

617-522-7282

Melatonin, as many know, is the master hormonal circadian. What many don’t know is that melatonin has effects on bodily function homeostasis in the form of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, prevention mitochondrial dysfunction and liver injury, as well as immune properties that can aid in therapy for many disease states including sepsis.

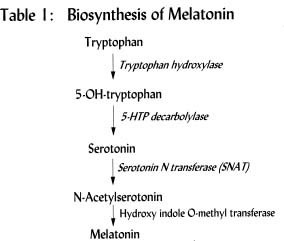

Melatonin is a polypeptide that is present in almost all organisms. It is derived from tryptophan, with its synthetic pathway differing between plants and animals. Table 1 shows the synthetic pathway in animals, which takes place for the most part in mitochondria.

Melatonin is a polypeptide that is present in almost all organisms. It is derived from tryptophan, with its synthetic pathway differing between plants and animals. Table 1 shows the synthetic pathway in animals, which takes place for the most part in mitochondria.

The original function of melatonin was a radical scavenger and antioxidant. Through evolution, melatonin became a signaling molecule involved in environmental photoperiodic information and ultimate endocrine messaging. In higher organisms synthesis occurs in the pineal gland and secretion is regulated by activation of b-1 adrenergic receptors. Its release is regulated by exposure to glue light, and is affected by both intensity and duration of exposure. Melatonin is released into circulation and reaches higher level concentrations at night and lower concentrations during the day. ¹

Melatonin has both anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. It is also involved in processes that involve apoptosis. Free radicals can lead to protein, lipid and DNA damage. Melatonin exerts its antioxidative function directly through its radical scavenging ability, indirectly through stimulation of antioxidant enzymes, and via stimulation of synthesis of other antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase. Melatonin is different for other classic antioxidants in that it participates in a ‘cascade reaction’. Via this mechanism, one melatonin molecule has the capacity to scavenge up to 10 reactive oxygen species versus the classic antioxidants that can scavenge one or less. This is compared to other antioxidants which include vitamin C, vitamin E, glutathione and NADH. In most cases melatonin is superior to these molecules. 2

Melatonin can also reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine levels. In a murine model of sepsis, melatonin decreased inflammation as evidenced by decreases in serum levels of TNF- a as well as IL-6. It has also been shown to affect levels of anti- inflammatory cytokines like IL-10. ¹

The above properties possessed by melatonin aid in prevention of mitochondrial dysfunction. This is one of the most important properties of melatonin, as it pertains to systemic disease conditions such as sepsis and liver disease, among others. Melatonin reaches high concentrations in mitochondria and is involved in many pathways which protect cells from oxidative stress. It regulates mitochondrial respiration and protects mitochondria from excess nitric oxide by blocking overexpression of inducible nitric oxide synthase.3 Melatonin can aid in normalizing ATP production during sepsis1, and can reverse the inhibitory action of LPS which leads to restoration of mitochondrial membrane potential, imperative for cellular function and respiration.

Studies examining critically ill patients have shown that these patients exhibit reduced melatonin secretion both nocturnally and during the day. In particular, septic patients have revealed that the circadian rhythm of melatonin is altered in the early stages of disease. The resultant changes in melatonin secretion alters pro-inflammatory cytokine release, reflected in an overall increase in these patients. These findings likely reflect the possible link between the detrimental alterations in circadian rhythm and the progression of early stage sepsis.4 Critically ill patients exhibit severely reduced melatonin levels both at night (where it should peak) and during the daytime.5

Melatonin as a therapeutic has been evaluated in sepsis and related organ complications involving the liver, heart and brain. Melatonin has also been evaluated in treating fatty liver disease, toxin-induced liver injury, and renal injury associated with ureteral obstruction. In septic patients, oxidative imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction are common features that lead to organ dysfunction and cell death. Melatonin is becoming a promising adjunctive drug for sepsis through its anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and antioxidant properties outlined above.1 With oral administration in the study among patients in intensive care unit settings, pharmacological levels are reached within five minutes and were maintained up to 10 hours following administration. There were no adverse side effects.5

In liver disease, oxidative stress is a key factor in causing progression of disease be it systemic disease (sepsis); non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, toxin-associated hepatopathy, neoplasia, hepatitis and fibrosis. The liver is the only organ where melatonin is metabolized, and has high intracellular concentrations.6 Melatonin once again is a potent antioxidant in the liver, via free radical scavenging and stimulation of antioxidant enzymes. The literature has shown that melatonin may be indicated in reducing liver damage after sepsis, hemorrhagic shock, ischemia/ reperfusion, and in many models of toxic liver injury.7

Melatonin administration is safe and effective, can be given orally or IV, and is essentially devoid of clinically relevant side effects. Studies in people have evaluated doses at 3, 10, 20, 50 and 100 mg with no adverse effects.1 Daytime drowsiness appears to be the one side effect, and usually is not clinically significant. The lethal dose is actually reported to be infinity!1 In our critical care unit at Angell, I will begin to use dosages of 3-10 mg per patient, at night, for sepsis and other organ dysfunction associated with severe oxidative stress such as hepatic failure, severe pancreatitis and severe diseases of the kidney and gastrointestinal tract.

References

- Ruben Manuel Luciano Colunga Biancatelli, Ma Berril, Yassen Mohammed, Paul MarikJ. Melatonin for the Treatment of Sepsis: The Scientific Rationale. J Thorac Dis 2020 feb; 12 (suppl 1); S54-S65.

- Tan D-X, Manchester LC, Esteban-Zubero E, et al. Melatonin as a Potent and Inducible Endogenous Antioxidant: Synthesis and Metabolism. Molecules 2015;20:18886-906.

- Acuña-Castroviejo D, Escames G, López LC, et al. Melatonin and nitric oxide: two required antagonists for mitochondrial homeostasis. Endocrine 2005;27:159-68.

- Li CX, Liang DD, Xie GH, et al. Altered melatonin secretion and circadian gene expression with increased proinflammatory cytokine expression in early-stage sepsis patients. Mol Med Rep 2013;7:1117-22.

- Mistraletti G, Sabbatini G, Taverna M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered melatonin in critically ill patients. J Pineal Res 2010;48:142-7

- Mortezaee K, Khanlarkhani N. Melatonin application in targeting oxidative-induced liver injuries: A review. J Cell Physiol 2018;233:4015-32.

- Mathes AM. Hepatoprotective actions of melatonin: possible mediation by melatonin receptors. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:6087-97.

- Ozbek E, Ilbey YO, Ozbek M, et al. Melatonin attenuates unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced renal injury by reducing oxidative stress, iNOS, MAPK, and NF-kB expression. J Endourol 2009;23:1165-73.

- Tordjman S, Chokron S, Delorme R, et al. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017;15:434-43