-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

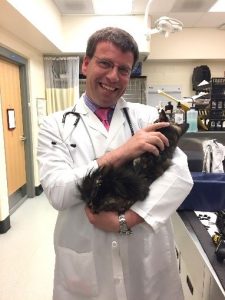

Klaus Loft, DVM

Klaus Loft, DVM

angell.org/dermatology

dermatology@angell.org

617-524-5733

The diagnosis and treatment of dermatophytosis in cats and dogs can often be a frustrating task for both clinicians and pet owners.

Review papers are a valuable way for keeping up to date on topics of clinical relevance for most clinicians. The World Association of Veterinary Dermatology (WAVD) has provided guidelines on the best practice of care for felines and canines pertaining to several topics including dermatophytosis. Although this article provides more information than most veterinarians in New England will require, it serves as a good source for advice on diagnostics, treatment options and follow-up for cases of ringworm for almost all clinical scenarios. The full original 40 page text and others like it are available for free at www.WAVD.org under the continued education section.

This is a summary and review with my subjective comments on the consensus statement from the above published review article in Veterinary Dermatology in late 2017 by an international group of veterinary specialists in mycology, dermatology and clinical diagnostics.

In my view the best approach to a small animal patient with suspected dermatophytosis should be the same as the approach to any other dermatologic patient: conducting a good patient medical history review and asking questions about recent history of travel to areas or regions with a higher endemic risk for dermatophytosis than New England including questions about adoption or kenneling.

- Are other pets and/or humans in the household affected?

- Has there been contact with other pets with increased risk? (Persian cats, shelter animals, feral or barn animals, new kittens or puppies introduced into the household)

- Has there been recent breeding (because mating could be a possible source of exposure)?

Clinical findings include alopecia with broken hair, crusting, generally not very pruritic folliculitis or pustular dermatitis. In severe cases we can see deep pyoderma, furunculosis and draining tracts (Photo 2).

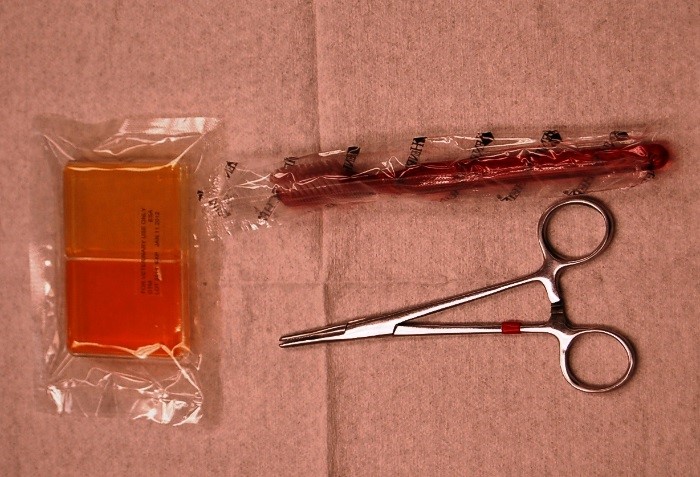

Quote from the WAVD summary, “Dermatophytosis is diagnosed by utilizing a number of ‘imperfect’ complementary diagnostic tests, including Wood’s lamp and direct examination to document active hair infection, dermatophyte culture by toothbrush technique (photo 1) to diagnose fungal species involved and monitor response to therapy, and biopsy with special fungal stains for nodular or atypical infections.”

The use of Woods lamp is a good, cheap and minimally-invasive tool to have at hand, and is considered a better tool than we generally had believed for assisting in detection of microsporum canis and possible other dermatophyte forms (photos 3 & 4). Keep in mind that a negative Wood’s lamp exam does not rule out dermatophytosis. Tooth brushing of the fur coat for collecting sample material is superior to plucking a few hair strands for dermatophyte culture and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The use of PCR can be a good option for a faster turn-around test result (3-5 days with most commercial laboratories). The PCR has a good correlation in detection and confirmation of likely ringworm infection. PCR is not always the best option for monitoring success of “mycological cure.” The use of cultures and fungal strain identification is a better option. I prefer sending the samples to a laboratory for growth and identification over in-house tests, where we can see a huge inter-personnel variation in sensitivity and specificity.

Numerous protocols are available to treat dermatophytosis systemically for both dogs and cats allowing for tailoring of treatments for each patient. Given the varied treatment options, recommendations for treatment can be found in the WAVD dermatophyte guidelines, in Plumb’s Veterinary Handbook, or by contacting the Angell Dermatology Service for advice. The use of non-compounded itraconazole, fluconazole and terbinafine are very effective for both dogs and cats. The use of systemic ketoconazole should likely be limited to non-pregnant or non-breeding dogs. The risk of side effects when used in cats appears to outweigh the potential benefits, which include lower cost. The use of Griseofulvin should be a last resort as the side effects and monitoring would far outweigh any benefits compared to newer options. Treatment with systemic Lufenuron or topical chlorhexidine alone is not considered effective and should not be recommended.

We recommend that treatment continues until 2 negative cultures 21 to 30 days apart are obtained.

Below is a summary of the WADV consensus guidelines on dermatophytosis. I have added in bold the New England regions’ take on the subject based on New England data as well as clinical experiences collected here at the Angell Animal Medical Center from patients referred from our colleagues across the region.

1) Prevalence and risk factors

a) Determination of the true regional prevalence and breed predispositions for dermatophytosis is difficult because this is not a spontaneously occurring disease, it is not reportable and it is not a fatal disease. Infection varies in severity and resolves without treatment in many dogs and cats. All of these factors bias breed and prevalence predilection data and might even change over time.

b) Subcutaneous dermatophytic infections (kerions, myocytoma and “pseudomyocytoma,” slightly more common would be furunculosis from infected hair follicles shown in photo 2) have been reported most commonly in Persian cats, and Yorkshire terrier dogs, but are generally rare in cats and extremely rare in dogs.

c) The activities of working and hunting dogs may increase their risk of exposure to dermatophyte spores resulting in superficial and nodular lesions. Very rare in this region, unless within 12-18 months of travel outside New England.

d) Seropositive FIV and/or FeLV status in cats alone does not increase the risk of dermatophytosis. This is often a misconception among pet owners and breeders.

2) Diagnostic testing

The sum of test results, signalment and clinical findings should generate an index of suspicion for dermatophytosis and be the best way to determine when to treat or not to treat.

a) No one test was identified as a “gold standard.”

b) Dermatophytosis is diagnosed by using a number of “imperfect” complementary diagnostic tests, including Wood’s lamp and direct examination to document active hair infection, dermatophyte culture by toothbrush technique (photo 1) to diagnose fungal species involved and monitor response to therapy, and biopsy with special fungal stains for nodular or atypical infections.

c) Dermoscopy may be a useful clinical tool with or without concurrent use of a Wood’s lamp to identify hairs for culture and/or direct examination. This requires a little getting used to but can be a helpful tool.

d) PCR detection of dermatophyte DNA can be helpful, however a positive PCR does not necessarily indicate active infection, as dead fungal organisms from a successfully treated infection will still be detected on PCR, as will non-infected fomite carriers. Do not use the PCR as follow up sampling or to monitor for treatment effect.

e) Contrary to what is believed, Wood’s lamp examination (photo 3 & 4) is likely to be positive in most cases of canis dermatophytosis, So use the Wood’s lamp to optimize your collection for this particular dermatophyte. Fluorescing hairs (photo 3) are most likely to be found in untreated infections. Fluorescence may be difficult to find in treated cats. False positive and false negative results are usually due to inadequate equipment, lack of magnification, patient compliance, poor technique or lack of training. This technique requires a little getting used to, but is very helpful in identifying where to sample for DTM during treatment.

f) Monitoring of response to therapy includes clinical response, use of Wood’s lamp if possible, and fungal culture on Dermatophyte Test Medium (DTM). The number of colony forming units is helpful in monitoring response to therapy. Do not use the PCR to monitor for treatment success.

g) A negative PCR in a treated cat is compatible with cure. Negative fungal culture from a cat with no lesions and a negative Wood’s lamp exam (except for glowing tips) is compatible with cure. (THIS IS VERY IMPORTANT).

3) Topical antifungal treatments

a) Twice weekly application of lime sulfur, enilconazole (not available in the US for use in animals) or a miconazole/chlorhexidine shampoo are currently recommended effective topical therapies in the treatment of generalized dermatophytosis in cats and dogs.

b) Accelerated hydrogen peroxide products (Accel® TB) as well as climbazole and terbinafine shampoos show promise, but cannot be definitively recommended until more in vivo studies documenting efficacy are available. Recommending this to clients can be helpful, but might bring a false sense of effectiveness in some cases.

c) Miconazole shampoos are effective in vitro but in vivo are most effective when combined with chlorhexidine. Recommending this to clients can be helpful, but might bring a false sense of effectiveness in some cases.

d) Chlorhexidine as monotherapy is poorly effective and is not recommended. The concentration and/or formulation is irrelevant, it should not be used as a stand-alone treatment.

e) For localized treatment, clotrimazole, miconazole and enilconazole have some data to document effectiveness. These are recommended as concurrent treatments, but not as sole therapy. Recommending this to clients can be helpful, but might bring a false sense of effectiveness in some cases.

4) Systemic treatment

a) Itraconazole (non-compounded) is likely the best option in cats, but anorexia and/or hepatotoxicity can occur. Compounded itraconazole has been shown to be unstable and at best have unreliable effectiveness, so non-compounded itraconazole is recommended. Together, Terbinafine and itraconazole are the two most effective and safe systemic treatments for dermatophytosis in both cats and dogs able to tolerate these drugs.

b) Griseofulvin is effective but also has more potential side effects compared to itraconazole and terbinafine.

c) Ketoconazole and fluconazole are less effective treatment options and ketoconazole has more potential for adverse side effects. I do not recommend using them in cats.

d) Lufenuron has no in vitro efficacy against dermatophytes, does not prevent or alter the course of dermatophyte infections, does not enhance the efficacy of systemic or topical antifungal treatments, and has no place in the treatment of dermatophytosis.

e) Antifungal vaccines do not protect against challenge exposure but may be a useful adjunct therapy.

5) Environmental disinfection

This can become a source of significant frustration with owners as the risk of relapse and/or human exposure is a difficult topic for many.

a) Environmental decontamination’s primary purpose is to prevent fomite contamination and false positive fungal culture results.

b) Infection from the environment alone is rare.

c) Minimizing contamination can be accomplished via clipping of affected lesions, topical therapy and routine cleaning. Helping owners with instructions on how to set up and manage a quarantine area at home can be helpful in multi-pet households. Further showing owners how to keep infected animals separate from non-infected animals can reduce the cost of treatment and testing.

d) Confinement needs to be used with care and for the shortest time possible. Dermatophytosis is a curable disease, but behavior problems and socialization problems can be life-long if the young or newly adopted animals are not socialized properly. Veterinarians need to consider animal welfare and quality of life when making this recommendation.

e) Infective material is easily removed from the environment. If it can be washed, it can be decontaminated.

6) Zoonotic considerations

a) Dermatophytosis is a known zoonosis and causes skin lesions which are treatable and curable.

b) Dermatophytosis is a common skin disease in people but the true rate of transmission from animals to people is unknown (risk of “reverse zoonosis” or zooanthroponosis is also unknown).

c) In people, the predominant dermatophyte pathogen is non-animal derived rubrum and the most common clinical presentation in people is onychomycoses (i.e. “toe nail fungus”).

d) The most common complication of canis infections in immunocompromised people is a prolonged treatment time.

Reference:

KA Moriello, K Coyner, S Paterson, B Mignon. Diagnosis and treatment of dermatophytosis in dogs and cats. Vet Dermatol 2017;28:266-e68.