-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Klaus Loft, DVM

Klaus Loft, DVM

dermatology@angell.org

angell.org/dermatology

617-524-5733

Dealing with autoimmune blistering skin diseases (ABSD) is a complex and frustrating aspect of clinical practice. Pemphigus foliaceus (PF or simply pemphigus) is one of the more common autoimmune blistering skin diseases in referral practice, yet the prevalence of PF as reported in the literature is less than 2% for dogs and likely less than 1% in feline patients seen in tertiary referral practices.

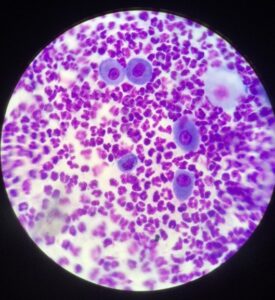

Pathophysiology: Pemphigus foliaceus occurs due to an immune mediated attack on different elements of desmosomes in the epidermis, causing a breakdown (acantholysis) of the cell to cell connections causing subcorneal pustules. The condition is seen in humans, dogs, cats, goats, equids, mice and rabbits. The specific desmosome structure affected in a majority of PF patients is slightly different between humans and dogs (desmoglein 1 and desmocollin 1, respectively) and there are likely a multitude of mechanisms causing the acantholysis to occur, which causes the keratinocytes to “round up” with a unique “fried egg” appearance on cytology. Pemphigus can be idiopathic, paraneoplastic or drug induced. Other forms of pemphigus exist such as pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vegetans, but they are even less common in the clinical setting and they have other immunologic targets, distribution of clinical signs, and prognoses.

Signalment: Dogs that develop pemphigus are usually middle aged (5-7 years old) and commonly affected breeds are the chow chow, Akita, dachshund, and bulldogs. Cats with PF are also often middle aged to older (7+ years old). There is no known sex predisposition in cats or dogs.

Clinical signs/lesion distribution: In dogs, there is often acute onset with often rapid progression of lesions (a few days to a week). Generalized or locally extensive involving the head, face, and ears. Often, initially not affecting the planum nasum, but can progress to affect even non-haired skin, like planum nasum (photo 2) and paw pads. Mucous membranes are often unaffected, but mucocutaneous junctions (lip, eyes, vulva/prepuce and rectum) will often have lesions as part of the clinical picture.

Cats also show an acute onset of severe crusting of concave pinna, periocular areas extending onto the muzzle and lip margins (photo 5). Purulent paronychia (photo 3) with multiple digits being affected can be seen. Crusting lesions can occasionally be found on the area around the nipples.

Most distinctive for PF is the development of subcorneal pustules, but due to the duration of illness and patient activity, intact pustules are often hard to identify. Instead, pemphigus is manifested as heavy serous (yellow) crusting. Depigmentation is often noted with chronic disease. Pustule formation on the concave pinna or focal serous crusting on the concave pinna should always ring a bell for possible pemphigus foliaceus in both cats and dogs. Although these lesions look infected, they typically are not. Pruritus can be variable and is usually due to secondary skin infections. If the disease is generalized then systemic signs can be seen such as fever, lethargy, anorexia, limb edema, and lymphadenopathy.

Differential diagnoses: Pemphigus foliaceus can easily be confused with a secondary bacterial and/or malassezia pyoderma, demodex, dermatophytosis, hepatocutaneous syndrome, and epitheliotropic lymphoma (a.k.a. mycosis fungoides), and drug eruptions. PF is also known as one of the big allergy mimickers, so ruling out allergic disease is important as well. Although allergic skin disease and PF can be identified in the same patient, they are not known to be linked conditions.

Diagnosis: Cytology is usually the first step for a diagnosis of this disease. Collection of a sample from an intact pustule is ideal, but if that cannot be found, sampling the underside of an adherent crust will be adequate. Numerous neutrophils and eosinophils are common along with acantholytic keratinocytes (photo 1), and no bacteria. Skin biopsies are needed to confirm a diagnosis of PF in cats and dogs. Collect biopsies from the most recent lesions that should include an intact pustule if present, or a heavy adherent crust. It is very important that the crust is included with the biopsy and not disturbed if possible. Therapy for PF will often result in changes to the CBC/chemistry/UA so baseline values are important, even though there are no pathognomonic changes seen in this condition.

Treatment: In the ER, the most ideal treatment modality will be immune suppressive dosages of short acting glucocorticoids. The initial dosage should be based on the systemic symptoms (fever, anorexia, malaise) the patient presents with as well as the severity of dermatologic lesions. Prednisone can be used in dogs from 0.5 to 2.0 mg/kg/day, and prednisolone is usually used in cats at 1 to 4 mg/kg/day. If secondary infection is present on cytology, then consider systemic antibiotic treatment in addition.

We often manage pemphigus in dogs with a combination of steroids and azathioprine. Brand name micro emulsified cyclosporine (Atopica) can be used as single therapy or as part of a polypharmacologic management of PF dosage for dogs orally at a range of 5-10 mg/kg q 12 to 24 hrs. In large breed dogs where Atopica effect can be slow to show clinical impact and can be too costly for many clients, the addition of ketoconazole or fluconazole can boost blood and tissue levels of cyclosporine, which can allow for a dose reduction of that drug – and a cost savings. Other steroid-sparing options could be a combination of tetracycline or doxycycline combined with niacinamide ‑ again either as single therapy or as part of a multi drug regimen. Anecdotal treatments with hydroxychloroquine have been helpful to reduce cost of long term care.

For cats, the use of azathioprine is contraindicated, so prednisolone/methylprednisolone is the first line treatment but can be combined with liquid cyclosporine. Liquid oral atopica can be used as single agent therapy for PF in cats at 7-10 mg/kg q 12-24 hrs. We do not use ketoconazole or fluconazole in conjunction with Atopica in cats. Less frequently used for cats with PF is chlorambucil. These steroid-sparing drugs are often used in cats when the patient is unable to tolerate long term steroid monotherapy.

Typically, patients are continued on these medications until the disease is considered to be in remission and then we taper slowly to the lowest effective dose. Drugs should be tapered over a 3-5 month period and patients should be closely monitored for flare-ups. Regular blood work and urine evaluation should be performed for possible systemic side effects of treatment (steroid-induced hepatopathy, diabetes, calcinosis cutis, secondary opportunistic bacterial skin and/or urinary tract infections, and upper respiratory infections in cats). Depigmented skin will often be at risk for solar-induced problems (sun burn, discoid lupus erythematosus, Bowen’s disease, squamous cell carcinoma).

The dermatologic symptoms can be medically managed in many cases, but often the worst complications arise from side effects of the immune suppressive medications. Pemphigus foliaceus can often have a waxing and waning course even when medically managed aggressively.

References

- Olivry, T.: “A review of autoimmune skin diseases in domestic animals: I – Superficial pemphigus” Veterinary Dermatology 2006. 17; 291–305

- Bizikova, P., Linder K.E. and Olivry T:” Immunomapping of desmosomal and nondesmosomal adhesion molecules in healthy canine footpad, haired skin and buccal mucosal epithelia: comparison with canine pemphigus foliaceus serum immunoglobulin G staining patterns” Veterinary Dermatology, 22, 132–142

- William Miller Craig Griffin Karen Campbell Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology 7th Edition.

Photo 2. Canine pemphigus foliaceus crossing the barrier from haired skin to the planum nasum