-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Jillian Walz, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology)

By Jillian Walz, DVM, DACVIM (Oncology)![]()

DACVR (Radiation Oncology)

angell.org/oncology

oncology@angell.org

617-541-5136

Radiation therapy is increasingly used in veterinary patients undergoing cancer treatment. In this setting, the most commonly employed radiation therapy technique is external beam radiation. Radiation is delivered using a beam of high energy x-rays generated outside the patient (typically with a linear accelerator) and aimed at surface or internal targets. High-energy electrons may also be used to treat targets on the surface. With recent advancements in radiation therapy planning technology, we are now able to aim the radiation beam much more precisely at our target using image-guided, computer-based treatment planning (i.e. intensity-modulated radiation therapy, or IMRT). This has resulted in decreased incidence and severity of skin side effects in many patients; however, in patients with tumors close to or even in the skin, radiation can result in skin changes and side effects.

Overview of Radiation Side Effects

There are two major categories of radiation side effects: acute effects and late effects.

Acute radiation side effects typically occur during or within a few weeks after treatment, due to death of rapidly dividing cells and concurrent inflammation. These side effects are transient, and begin to heal within 2-3 weeks of RT completion. Complete healing may take up to 1-3 months in some cases. Acute radiation side effects are more likely to occur with full-course radiation (i.e. 10-20 daily treatments).1

Late radiation side effects occur months or years after treatment as a result of fibrosis and vascular changes. These complications are often permanent and in some cases may be severe. Risk of late radiation side effects increases with larger doses per treatment, as in hypofractionated (palliative-intent) or stereotactic protocols.1

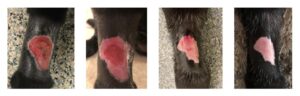

A patient with moist desquamation following full course radiation therapy (19 treatments). Photos taken at 7, 13, 25, and 42 days following radiation therapy.

Acute Radiation Dermatitis: Pathophysiology

Within several hours of radiation treatment, temporary hyperemia and erythema may occur due to local capillary dilation. This is not typically accompanied by any discomfort.2

Under normal conditions, the stem cells in the basal layer of the epidermis continually divide to replace skin cells as they mature and eventually exfoliate. This process is interrupted by radiation-induced death of these rapidly dividing basal keratinocytes, resulting in breakdown of the skin barrier. About 2-4 weeks into treatment, this can manifest as dry desquamation (nonpainful flaking of upper skin layers) progressing to moist desquamation (moist dermatitis with exudate). Moist desquamation is generally painful, and patients are left susceptible to secondary infection of affected areas. Activation of local inflammatory pathways and mast cell degranulation further contribute to inflammation and discomfort.3

Hair follicles and adnexal glands are also radiosensitive at fairly low doses of radiation. Most patients receiving radiation to targets at or near the skin will experience hair loss which may be temporary or permanent.

Considerable variability is observed between patients in regards to incidence and severity of radiation dermatitis. In humans, established risk factors such as skin tone, smoking, and certain comorbidities or genetic factors are useful to identify patients who may experience more florid acute dermatitis. No prognostic factors have been identified in veterinary patients. However, there are certain anatomic locations recognized as being at increased risk for severe dermatitis. This includes regions with skin folds (i.e. facial folds in brachycephalic breeds), footpads, periocular skin, and the perineum.4

Acute Radiation Dermatitis: Treatment

There is no agreed-upon standard of care for treatment of radiation dermatitis. A meta-analysis of 20 clinical trials using various topical treatments in human radiation patients failed to find evidence that any agent provided effective treatment or prevention of radiation dermatitis. Topical steroids are not recommended in human patients as they can contribute to skin thinning and increase the risk of infection.5

Very few studies have addressed the management of radiation dermatitis in veterinary patients. A survey of veterinary radiation facilities found wide variability in management strategies between institutions.6 A placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating the use of oral steroids (prednisone) in dogs undergoing RT showed no difference in the timing, incidence, or severity between dogs treated with steroids versus placebo.7 Another prospective trial evaluated prophylactic antibiotic treatment in canine radiation patients. This study showed no improvement in incidence or severity of dermatitis, and also found an increase in multidrug-resistant infections in dogs treated with prophylactic antibiotics. The authors therefore concluded that prophylactic antibiotic therapy is not recommended in canine radiation patients.8

A patient with severe self-trauma after near-complete healing of radiation site. Photos taken at 42, 56, 118, and 138 days following radiation therapy.

With little evidence-based medicine to guide treatment or prevention of acute radiation dermatitis, each institution typically develops their own protocols. Here at Angell, our approach is adapted to the severity and location of dermatitis in each individual patient:

- In patients experiencing mild dermatitis limited to hyperemia and dry desquamation, no therapy is recommended. Patients experiencing pruritus are often prescribed diphenhydramine.

- E-collars are recommended at the first sign of dermatitis to prevent self-trauma. Self-mutilation of radiation sites can result in devastating complications due to delayed healing and secondary infection.

- In patients with exudative/moist dermatitis, oral pain medications such as NSAIDs, gabapentin, and amantadine are proactively prescribed. Parenteral analgesia may be used in patients with severe discomfort, including fentanyl patch placement and local nerve blocks in amenable locations.

- Sites are shaved and cleaned at the first sign of moist dermatitis, and SSD ointment applied daily during anesthesia to non-periocular/facial sites. In patients amenable to it, owners are instructed to apply SSD ointment at home 1-3 times daily.

- Patients with periocular or facial dermatitis are prescribed triple antibiotic or erythromycin ophthalmic ointment for daily application.

- Systemic antibiotics such as cefpodoxime or Clavamox are prescribed in patients with moderate to severe dermatitis to prevent or address secondary infection.

- Skin cytology may be performed in patients where secondary bacterial or fungal infection is suspected.

- Wound dressing is NOT typically recommended as radiation dermatitis is often highly exudative.

- Avoiding sun exposure is recommended.

Late Radiation Side Effects

In most patients, chronic changes following radiation are cosmetic only and do not result in discomfort. Most patients undergoing radiation to sites at or near the skin will have some degree of alopecia, which may be permanent. Underlying skin may remain thin and pigmentation changes are common (both hypo- and hyperpigmentation). Hair that does regrow is often white or grey (leukotrichia).

Chronic skin changes are poorly described in veterinary patients but can include fibrosis, ulceration, and lymphedema (including edema of the distal limb in patients undergoing circumferential/full thickness irradiation of the limb). The inflammatory cytokine transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) is primarily implicated in late radiation side effects. Along with other inflammatory cytokines, increased expression of TGF-β results in fibrosis, endothelial damage, and – in severe cases – skin atrophy and necrosis.9

Oral pentoxifylline has shown promise in the treatment of radiation-induced fibrosis in humans, although prolonged treatment (years long) is often needed to elicit clinical effects.9 Pentoxifylline is generally well-tolerated in dogs and cats, with nausea and hyporexia being the most commonly reported side effects.10 Prophylactic use of pentoxifylline is not supported in the human literature.

In patients with chronic wound formation, surgical correction or even amputation may ultimately be required for wound management.

Conclusions

Acute radiation dermatitis varies between patients, and there is no agreed upon standard of care in either veterinary or human patients. Clinically relevant chronic skin side effects are uncommon following radiation in veterinary patients.

References

- Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ. Radiobiology for the Radiologist: Seventh Edition.; 2012.

- Leventhal J, Young MR. Radiation Dermatitis: Recognition, Prevention, and Management. Oncology (Williston Park). 2017;31(12).

- Kole AJ, Kole L, Moran MS. Acute radiation dermatitis in breast cancer patients: Challenges and solutions. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2017;9:313-323.

- Gieger T, Nolan M. Management of Radiation Side Effects to the Skin. Vet Clin North Am – Small Anim Pract. 2017;47(6):1165-1180.

- Chan RJ, Larsen E, Chan P. Re-examining the evidence in radiation dermatitis management literature: An overview and a critical appraisal of systematic reviews. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(3).

- Flynn AK, Lurie DM. Canine acute radiation dermatitis, a survey of current management practices in North America. Vet Comp Oncol. 2007;5(4):197-207.

- Flynn AK, Lurie DM, Ward J, Lewis DT, Marsella R. The clinical and histopathological effects of prednisone on acute radiation-induced dermatitis in dogs: A placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, prospective clinical trial. Vet Dermatol. 2007;18(4):217-226.

- Keyerleber MA, Ferrer L. Effect of prophylactic cefalexin treatment on the development of bacterial infection in acute radiation-induced dermatitis in dogs: a blinded randomized controlled prospective clinical trial. Vet Dermatol. 2018;29(1):18-37.

- Spałek M. Chronic radiation-induced dermatitis: Challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:473-482.

- Plumb DC. Plumb’s® 9th Edition Veterinary Drug Handbook.; 2018.