-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Steven Tsai, DVM, DACVR

By Steven Tsai, DVM, DACVR

angell.org/diagnosticimaging

diagnosticimaging@angell.org

617-541-5139

Thoracic radiographs in the coughing dog or cat can present a significant interpretive challenge for even the most experienced veterinarians. Evaluating the heart, pulmonary vessels, and pulmonary parenchyma provides a minimum baseline for determining the cause of a patient’s respiratory signs. Of those three, the pulmonary parenchyma typically poses the greatest challenge, as there is great variability and overlap between what normal and abnormal lungs look like. Cardiovascular structures, on the other hand, tend to be either big, or not big. This article will focus on radiographic evaluation of the pulmonary parenchyma, with brief overviews of both the classical pattern-based approach and an alternative approach based on macroscopic distribution of pulmonary abnormalities.

Most veterinarians are taught some version of the classical approach to pulmonary interpretation, focusing on the differences between interstitial, alveolar, and bronchial patterns. A distinction should be made between interstitial and alveolar patterns on the one hand, and bronchial patterns on the other, since two different sets of disease processes will typically lead to those two groups of patterns. The catch-all term “bronchointerstitial” is therefore somewhat unhelpful for narrowing down the differential list, since it encompasses nearly all causes of diffuse pulmonary disease. It is best to determine whether the primary pattern is bronchial, interstitial, or truly both at the same time.

Interstitial and alveolar patterns essentially sit at different points on a continuum and are created by degrees of increased pulmonary opacity which partially or completely obscure the pulmonary vessels. If pulmonary vessels are visible but have fuzzy margins, giving the appearance of “trees in a fog”, that is an interstitial pattern. If the vessels are completely obscured, that is an alveolar pattern (Figure 1). Air bronchograms may or may not be present in an alveolar pattern. In either case, the radiographic signs are caused by an accumulation of fluid (edema), hemorrhage, or cellular infiltrate (inflammatory or neoplastic) within the pulmonary interstitium, bronchioles, or alveoli. Interstitial and alveolar patterns can also be caused by partial or complete lung collapse (such as secondary to prolonged lateral recumbency), and typically is accompanied by a mediastinal shift towards the abnormal lung in that case. Typical differentials for interstitial and alveolar patterns in dogs include: cardiogenic or noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, bronchopneumonia (of which aspiration pneumonia is a sub-category), fibrosis, metastatic neoplasia, and pulmonary hemorrhage. The list for cats is similar, except that bronchopneumonia is exceedingly rare in cats and generally should not be considered in the absence of a recent anesthesia event or neurologic dysfunction which would impair the robust feline laryngeal reflex. In one study, out of over 31,000 cat necropsies during a 10 year period at a veterinary teaching hospital, only 39 cases of confirmed infectious pneumonia were found, and only 6 of those were attributable to aspiration of gastric contents (Macdonald, et al., 2003).

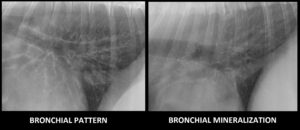

Figure 2 – Caudodorsal lungs on a lateral view in two dogs. Note the significant thickening of airways in the image on the left, compared with the thin-walled appearance of mineralized bronchi on the right. Bronchial mineralization is a common incidental finding in geriatric patients.

Bronchial patterns are generally distinct from interstitial and alveolar patterns, with the primary cause being thickening of the larger, conducting airways. The radiographic signs of a bronchial pattern are ring-like opacities (“donuts”) and parallel lines (“tram lines”). In cats, only donuts are recognizable, as the bronchi are generally too small to create visible tram lines. The appearance of the bronchial pattern may be exacerbated by an indistinct opacity surrounding the airway, termed “peribronchial cuffing”. This often leads to the bronchointerstitial appearance, but it is important to recognize that the bronchial pattern is the major one in these cases, as most often this indicates more severe or acute airway inflammation. Another common cause of a bronchointerstitial pattern is age-related fibrosis and mineralization of the interstitium and airways. Age-related bronchial mineralization leads to thin-walled, distinct bronchial opacities as opposed to the thick-walled, slightly indistinct appearance typical of a true bronchial pattern (Figure 2). For a true bronchial pattern, the primary differential is chronic lower airway disease of allergic (e.g., feline asthma, chronic bronchitis), infectious (e.g., tracheobronchitis a.k.a. “kennel cough”), or parasitic (e.g., lungworm, heartworm) etiology.

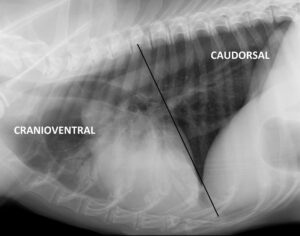

Figure 3 – Lateral view of a thorax delineating the difference between cranioventral and caudodorsal distribution. Note the air bronchograms indicating a cranioventral alveolar pattern in this dog, consistent with aspiration pneumonia.

While recognizing the distinction between interstitial/alveolar and bronchial patterns is important, an alternative method stresses the importance of lesion distribution (Nykamp, et al., 2002). With the exception of distinct nodules or masses, most pulmonary lesions are distributed cranioventrally, caudodorsally, multifocally, or asymmetrically. Cranioventral encompasses the entire left cranial, right cranial, and right middle lung lobes and is most commonly associated with bronchopneumonia, hemorrhage, neoplasia, and lung lobe torsion. Caudodorsal encompasses the left caudal, right caudal, and accessory lobes and is most commonly associated with cardiogenic or noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, pulmonary fibrosis, or neoplasia (Figure 3). It should be noted that there is no difference in the distribution of cardiogenic and noncardiogenic edema; differentiation is based on presence or absence of cardiomegaly or pulmonary venous enlargement. Feline cardiogenic edema is most commonly multifocal, often ventral, and commonly accompanied by variable degrees of pleural effusion. Metastatic carcinoma in cats also frequently presents as a multifocal indistinct pattern. Asymmetric lesions are most commonly seen with trauma (contusions), neoplasia, or bronchopneumonia.

By integrating the radiographic pattern and distribution along with the patient’s signalment, history, and physical exam findings, one can very often narrow down the source of coughing to cardiogenic, airway, or pulmonary parenchymal causes. Usually each cause branches further into just one or two reasonable differentials for the individual patient, which may require an additional diagnostic test (tracheal wash, heartworm test, etc.) or therapeutic trial (a dose of furosemide, a couple puffs of albuterol, etc.) to narrow down to a working clinical diagnosis.

For more information on Angell’s Diagnostic Imaging service or our online imaging consultative services, please visit angell.org/diagnosticimaging or call 617-541-5139.

References

BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Thoracic Imaging, ed. T Schwartz and V Johnson. (2008) British Small Animal Veterinary Association, Gloucester.

Macdonald E, Norris C, Berghaus R, Griffey S (2003) Clinicopathologic and radiographic features and etiologic agents in cats with histologically confirmed infectious pneumonia: 39 cases (1991-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 223(8): 1142-50.

Nykamp SG, Scrivani P, Dykes N (2002) Radiographic signs of pulmonary disease: An alternative approach. Compendium. 24(1): 25-35.