-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

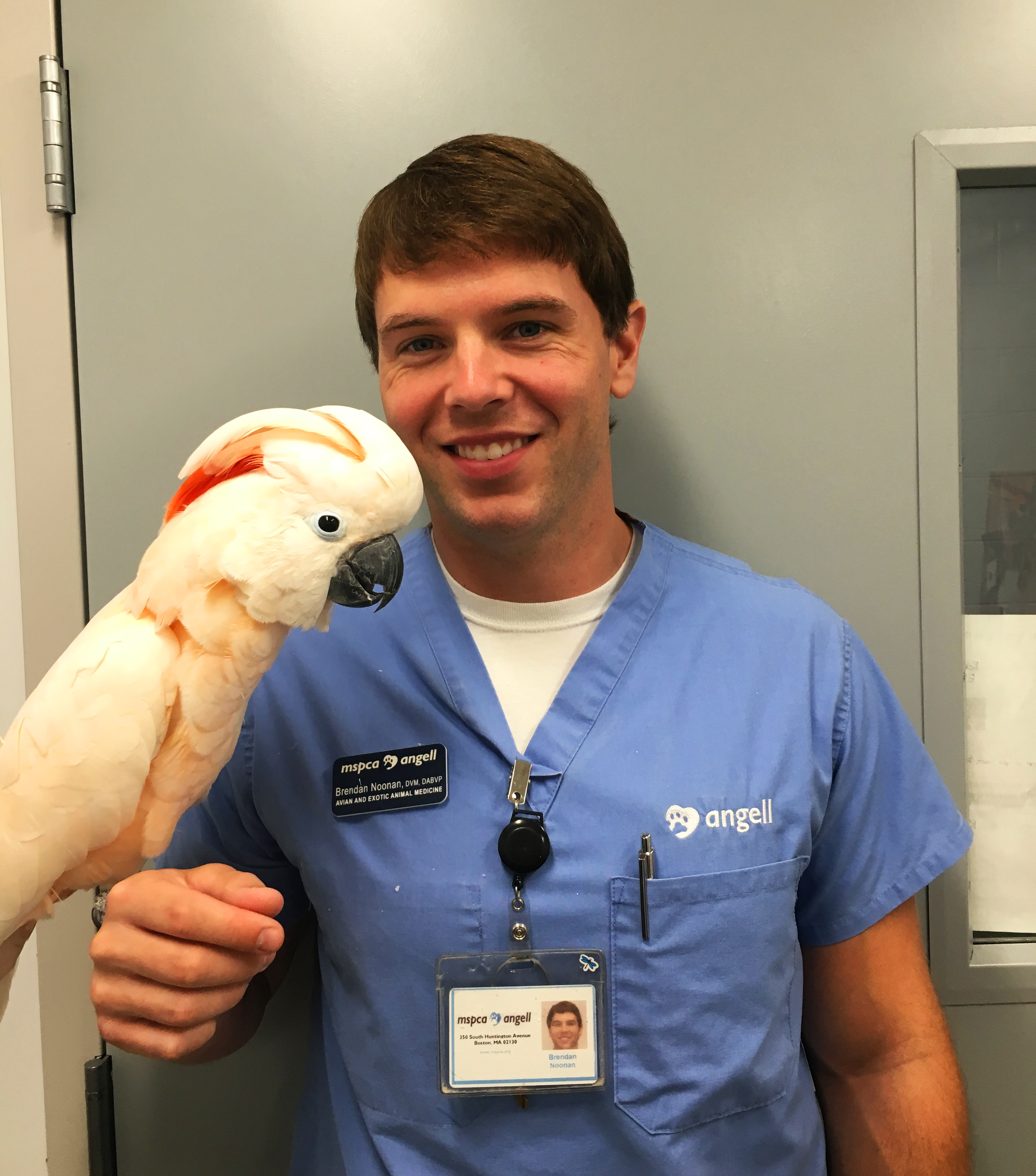

By Brendan Noonan, DVM, DABVP (Avian Practice)

By Brendan Noonan, DVM, DABVP (Avian Practice)

angell.org/avianandexotic

avianexotic@angell.org

781-902-8400

MSPCA-Angell West, Waltham

In recent years, the popularity of backyard chickens has grown considerably. Zoning legislation has created a platform for urban and suburban homeowners to legally invest in small flocks. The average home has fewer than ten birds and most cite egg consumption to be the primary purpose while pet ownership is a close second. In a recent USDA survey, less than half of flock owners were aware of common health concerns that could affect their flock. Respiratory diseases, while often not life-threatening, are one of the most commonly observed ailments by owners. Prevention and risk reduction are critical components for maintaining respiratory health, but recognizing symptoms is also important in guiding treatment.

Appropriate housing plays a large role in reducing the risk of respiratory infections. Whether you are converting an existing shed or purchasing a ready-made coop, it is important to determine the degree of ventilation it provides. During summer months, windows can be opened to improve air quality and air exchange. Birds that have access to a run are also exposed to fresh air. The frequency of respiratory infections increases during the fall when it’s cool at night but warm during the day. When the coop isn’t opened back up in the morning prior to increasing temperatures, a humidity spike will take a toll on the confined flock’s respiratory tract. A common misconception is that a coop needs to be airtight to improve heat trapping. In actuality, cracks at the seams along the roof lines allow for a limited exchange of cool air coming in, warming up, absorbing moisture, and then exhausting out of the coop again. Chickens are very efficient at staying warm so long as they are not in direct exposure to a draft. For this reason, windows don’t always allow for the best winter air exchange. If ventilation is lacking, the humidity created by the chickens and their feces will build up on the walls and windows. An ammonia level higher than 25ppm is enough to damage cilia in the airways of chickens, which allows respiratory pathogens to colonize and cause disease.

Acquiring healthy birds from the start is also a good way to prevent respiratory disease. The National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) was established in the 1930s as a cooperative state and federal program to take advantage of new found diagnostic capabilities, identifying and reducing incidence of Salmonella pullorum. This program has since expanded the scope of diseases to include Mycoplasma (M. gallisepticum, M. synoviae, M. meleagridis) and low pathogenic avian influenza. Many commercial hatcheries and farms conform to this voluntary program and are the ideal place to buy starter and replacement birds. Participation is often advertised, and if not, one should not hesitate to ask.

Acquiring healthy birds from the start is also a good way to prevent respiratory disease. The National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) was established in the 1930s as a cooperative state and federal program to take advantage of new found diagnostic capabilities, identifying and reducing incidence of Salmonella pullorum. This program has since expanded the scope of diseases to include Mycoplasma (M. gallisepticum, M. synoviae, M. meleagridis) and low pathogenic avian influenza. Many commercial hatcheries and farms conform to this voluntary program and are the ideal place to buy starter and replacement birds. Participation is often advertised, and if not, one should not hesitate to ask.

Being cognizant of biosecurity protocols can also protect a small flock from falling victim to contagious diseases. Many wild birds (e.g. sparrows, finches, etc.) that have access to the coop can spread diseases such as avian influenza, chlamydiosis, and avian tuberculosis. Exposure can also occur if chickens congregate under bird feeders when they have free range access. Water fowl such as geese are another reservoir for avian influenza and continuously shed. Chickens are likely to seroconvert but will shed the virus for life. Despite the risk wild birds pose, acquisition of new chickens is often the biggest risk factor for disease spread. Selecting birds from reputable suppliers that adhere to NPIP protocols is always advised. Adhering to a 6 week quarantine will also allow enough time to observe if any health concerns arise before introducing birds into an existing flock.

As the seasons change, the most common respiratory diseases observed by flock owners are non-specific respiratory infections. The typical snicks, sneezes and coughs will be heard but birds will often continue to eat and drink. Chickens are far less likely to look puffed up and sick as they would with other infections. Diagnostics are often not necessary as infections tend to be self-limiting and resolve within 7-10 days. Treatment with tetracycline antibiotics may reduce duration of symptoms by half. Ensuring optimum environmental conditions is most important during this time.

A top differential for non-specific respiratory infections is Mycoplasma gallisepticum (MG). Numerous species of mycoplasma are present in the US that cause disease in chickens as well as many that act as commensal organisms. As some of these organisms can be transmitted from the hen, through the egg, to the chick, this is another important reason to seek out an NPIP certified farm. Chickens affected by Mycoplasma gallisepticum can have mild clinical signs that typically escalate as secondary infections take hold. Snicks, sneezes and coughing will occur in affected birds. The flock will exhibit a decreased appetite and appear fluffed and lethargic. Premortem diagnosis can be achieved by serology, PCR, or culture and identification. Necropsy will reveal air saculitis and fibrinous polyserositis. A killed vaccine is available that will reduce clinical signs but will not prevent vertical and horizontal transmission. The standard course of treatment is injectable or water-based tylosin for a minimum of thirty days. Owners should be aware of the egg and meat withdrawal times after discontinuing antibiotic use. While clinical signs will improve, the organism is never completely cleared from the system.

Given the increased popularity of backyard chickens, it is important to inform owners about key factors that affect respiratory disease. Disease-free stock, properly ventilated housing, and appropriate biosecurity measures are not only important when raising a brood of chicks, but play an important role in maintaining a healthy flock. Owner education about common respiratory diseases is also important for early detection and treatment.

Sources:

Speer L. Brian. Current Therapy in Avian Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier 2016

Greenacre B. Cheryl, Morishita Y. Teresa. Backyard Poultry Medicine and Surgery. John Wiley and Sons 2015.

Elkhoraibi C. Blatchford R.A. Pitesky M.E. Mench J.A. Backyard Chickens in the United States: A Survey of Flock Owners. Poultry Science. Volume 93 Issue 11, 1 November 2014, Pages 2920-2931.