-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Pamela Mouser, DVM, MS, DACVP

By Pamela Mouser, DVM, MS, DACVP![]()

angell.org/lab

pathology@angell.org

617-541-5014

January 2022

I will never forget being at a fairly crowded birthday party when all of us attendees started to realize the pandemic was going to happen. There were lots of shared chip bowls on the buffet table that day. Yikes! From that moment, it was about a year (and no birthday parties) later when it appeared widespread vaccination was going to happen. Even as local coronavirus cases reached peak numbers, the overwhelming demand for veterinary care came as a real shock to most of us. Veterinary hospital capacities were splitting at the seams, and clients were lining up—outside in cars—for emergency visits, while exhausted veterinarians continued to provide the best care possible. And despite how it might have felt, the daily effort did make a difference to a whole lot of animals and their humans during a pretty traumatic time. In this article, I wanted to look back at some interesting cases submitted to Angell Pathology during the “pandemic year” to highlight a few challenges and successes we experienced.

Case 1: A sniffling cat gets a swollen face

A 10-year-old, indoor-only, domestic shorthair cat arrived at Angell with a several-month history of nasal congestion, sneezing, and mild oculonasal discharge. His clinical signs progressed to include facial swelling near the right orbit and mild buphthalmos OD. The cat’s prior treatments included antibiotics, antihistamines, and steroids, with no clinical improvement.

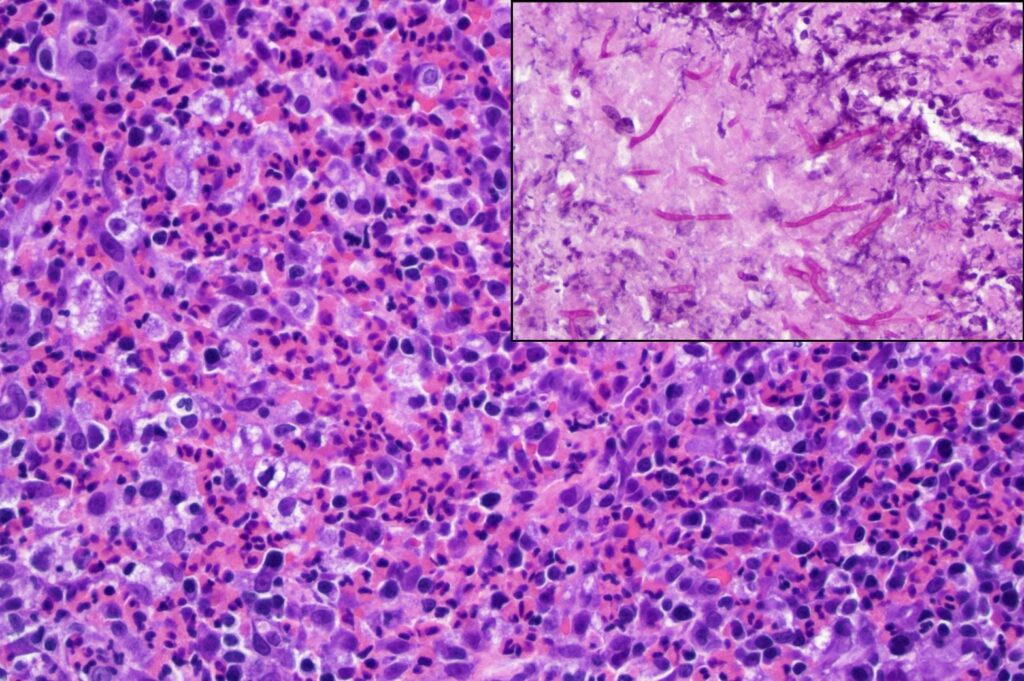

At the initial examination by Angell’s Internal Medicine Department, right-sided facial swelling was confirmed, and no airflow was detected through the right nostril. CT imaging revealed a right nasal/periorbital mass showing invasive behavior but not osteolysis. A malignant neoplasm was suspected. Initial histopathology of a blind biopsy from the right nasal cavity showed only mild mixed rhinitis. Subsequent retroflex rhinoscopy allowed better visualization and sampling of the mass described as “plaque-like” with multiple “pinpoint white lesions.” Histopathology of the retroflex sample consisted of intense inflammation characterized as eosinophilic and granulomatous, Figure 1. Rare fungal hyphae were identified with PAS reaction.

Figure 1. High magnification photomicrograph of the retroflex nasal biopsy, depicting sheets of eosinophils accompanied by macrophages and fewer small mononuclear leukocytes. Organisms are not evident in this view. HE stain, 400x. Inset: Branching fungal hyphae (magenta color) highlighted in orbital soft tissue. PAS, 400x.

Additional testing included Aspergillus antibody titer (detected at a dilution of 1:32), Aspergillus spp. PCR on formalin-fixed nasal biopsy tissue (negative) and fungal culture (identified Aspergillus sp.). The final diagnosis based on combined findings was nasal and orbital aspergillosis. Similar to the nasal biopsy, orbital soft tissue had marked eosinophilic, granulomatous inflammation but with more numerous fungal hyphae, Figure 1, inset. The right globe was removed, orbital tissue debulked, and clotrimazole infusion treatment was performed.

This cat was placed on long-term systemic antifungal treatment (initially terbinafine and itraconazole, later switched to posaconazole). The cat was doing very well at the time of the last visit. About 2.5 months after enucleation, the Aspergillus antibody titer had decreased from 32 to 2.

Sinonasal aspergillosis is uncommon in cats as compared to dogs. However, there is speculation that the more invasive sino-orbital form of aspergillosis, similar to what is described in our case example, represents an emerging infectious disease in cats.1 Aggressive treatment is recommended and includes a combination of debulking infected tissue, local treatment (in the form of intranasal infusion), and long-term systemic antifungal therapy.

Case 2: A squinting Pit Bull pup

An 8-month-old Pit Bull presented to Angell’s emergency service for swelling and cloudiness of the right eye (OD). About 1.5 weeks prior, the pup had reportedly gone outside to urinate and had returned with “seeds on her face.” The owner perceived swelling of the right eye. Empirical treatments before presentation included warm compresses and triple antibiotic ointment, with no improvement of swelling and progression to corneal clouding.

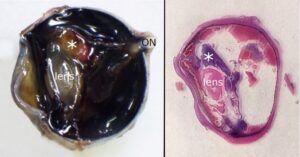

On presentation, the pet had severe blepharospasm, corneal edema and neovascularization, and mucoid discharge OD. Following evaluation by Angell’s Ophthalmology Department, the ophthalmic diagnosis was marked uveitis with associated glaucoma OD. Differentials included primary and secondary glaucoma (with potential causes of uveitis such as infection, trauma, or other severe intraocular disease considered). The veterinary team immediately initiated aggressive treatment for uveitis and glaucoma to retain vision, which was still detected on examination but had been impaired by inflammation. The eye was not visual the following day or a week later at ophthalmic recheck. Response of glaucoma and uveitis to medical management was considered poor. The prognosis for the globe was poor. The owner elected enucleation, and the sectioned globe is depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The formalin-fixed globe was bisected vertically through the optic nerve (ON). The left panel displays one-half of the submitted globe with cornea to the left. A tan mass (*) is closely associated with the lens. The retina is diffusely detached. The right image shows an equivalent subgross view of the sectioned, stained globe with cornea facing the left. The lens and basophilic material corresponding to the grossly-observed mass (*) are labeled. Red staining compatible with blood is present in the posterior globe (subretinal space), contributing to retinal detachment.

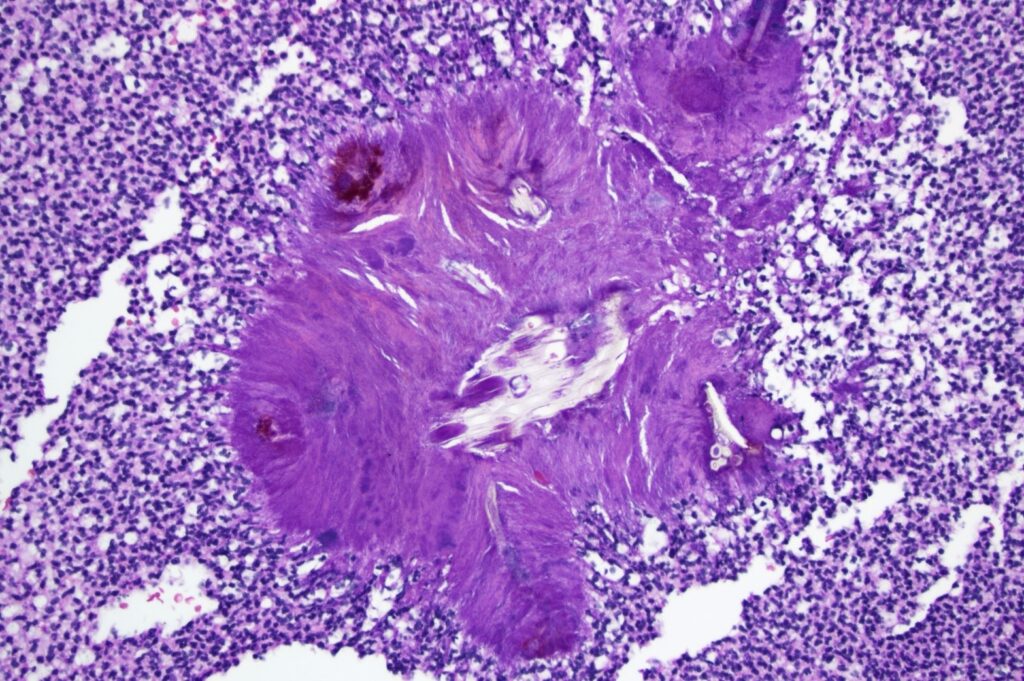

Microscopically, the globe contained sheets of intraocular degenerate neutrophils accompanied by numerous bacteria compatible with septic endophthalmitis. The grossly-observed tan mass consisted of dense suppurative exudate with embedded refractile, bacteria-laden foreign material of plant origin, Figure 3. The final microscopic diagnosis was septic suppurative endophthalmitis with intraocular plant foreign body.

Figure 3. Intermediate magnification photomicrograph depicting refractile foreign material, compatible with plant fiber, surrounded by radiating bacterial colonies and dense sheets of degenerate neutrophils. HE, 200x

In one retrospective study evaluating ocular foreign body trauma in dogs, young dogs (mean age just under 4 yrs old) were at increased risk. Enucleation was more likely in dogs with deep foreign body penetration, intense uveitis, and significant lens trauma.2 The pet, in this case, was unfortunately lost to follow-up after surgery.

Case 3: A cat with severe respiratory disease in the early months of the pandemic

A 6-year-old domestic shorthair cat with a two-week history of sneezing and nasal discharge became lethargic, anorectic, and dyspneic, prompting an emergency care visit. The only other medical history relayed by the owner was a recent (1 month prior) diagnosis of allergies being treated with Atopica. The owner and a second family member reportedly tested positive for and recovered from COVID-19 a few weeks before the cat developed clinical signs. The cat was quiet on initial presentation but became dull, continued to have increased respiratory effort, was anorectic, and became ataxic despite medical treatment during the first 24 hours. Thoracic radiographs on the day of presentation revealed diffuse airway disease with multifocal nodular soft tissue opacities in the lungs. Metastatic disease was a primary differential diagnosis. Additionally, at just two months into the pandemic, a few coronavirus-infected cats had been identified internationally, raising the public concern about feline susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. The clinical presentation, household history, and as-yet-unknown radiographic appearance of this new virus in cats placed atypical COVID-19 on the differential list.

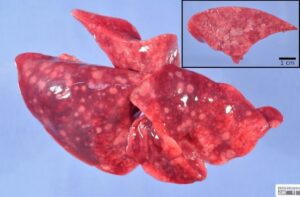

Clinical signs progressed to a dependence on the oxygen cage, resulting in the decision to euthanize the cat and submit it for postmortem examination humanely. At necropsy, all lung lobes contained disseminated, 2-5 mm, moderately firm, pale tan nodules that were mildly raised from the pleural surface and bulged from the parenchyma on cut section, Figure 4. Additional gross findings included regional lymphadenopathy and a mildly pale and friable liver.

Figure 4. All lobes of the excised right lung, collected postmortem, have pale tan nodules apparent from the pleural surface and (inset) bulging from the cut section of the parenchyma.

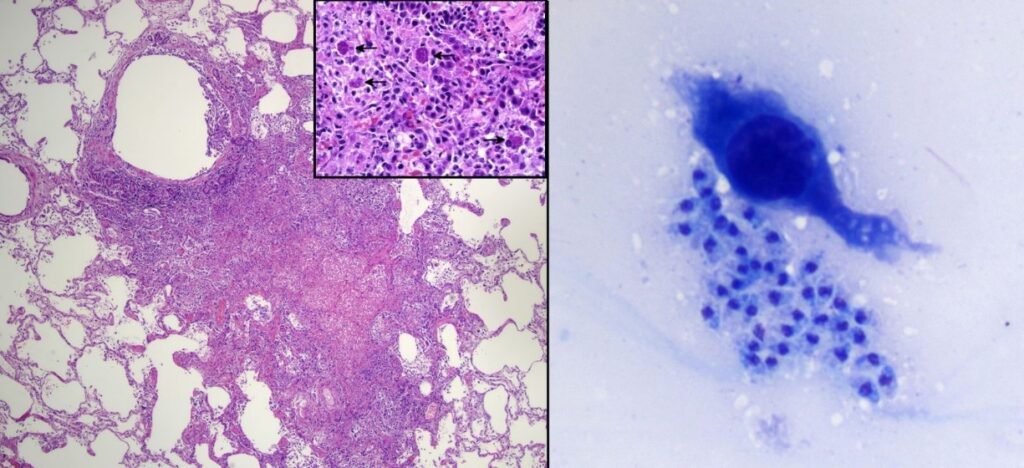

Histologically, the lung nodules consisted of pulmonary necrosis infiltrated by mononuclear leukocytes (multifocal necrotizing pneumonia). Frequent cells were distended by many ovoid to crescent-shaped protozoal tachyzoites, which were also observed in impression smear cytology of a lung nodule, Figure 5. Multiple additional organs examined microscopically (liver, spleen, heart, adrenal gland, lymph nodes) also had necrosis with intralesional protozoa, supporting a final diagnosis of disseminated toxoplasmosis.

Figure 5. A grossly-apparent lung nodule corresponds to necrosis with mononuclear infiltration (left, HE, 40x). On higher magnification, several cells contain clusters of protozoal tachyzoites (inset, HE, 400x). Impression smear cytology (right) also contains protozoa which appear extracellular in this field. DiffQuik, 500x

While clinical toxoplasmosis is uncommon in cats, there are several reports of acute clinical (also often systemic and fatal) infection in cats receiving cyclosporine treatment.3-5 In reported cases, cats had been treated with cyclosporine anywhere from 5 weeks to 8 months before developing clinical signs of toxoplasmosis. Similar to this case, a nodular appearance of pulmonary toxoplasmosis resembling the much more common lesion of metastatic neoplasia has been previously reported.6

Case 3: A frog with an extra bump

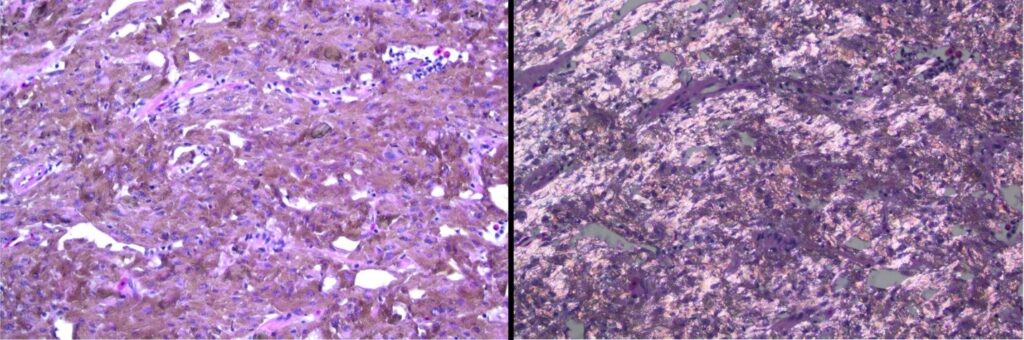

A 13-year-old Argentine Horned frog presented to the Angell Avian/Exotics Department for a 7 mm raised, white to brown, semi-firm cutaneous mass, Figure 6. Microscopically, the densely-cellular mass comprised round to slightly spindloid cells forming sheets and characterized by abundant cytoplasm filled with brown-yellow refractile crystalline pigment, Figure 7. Mast cells were observed on initial fine needle aspiration cytology. The mass was treated with diphenhydramine injections, but slow growth continued and was accompanied by periodic bleeding of the mass. Yunnan Baiyao and meloxicam were added; surgical excision was ultimately elected. The final diagnosis based on these histologic findings was iridophoroma.

Figure 6. A raised cutaneous mass with central ulceration protrudes from the frog’s dorsum. Note the variable pigmentation of the surface of the mass. Clinical photograph courtesy of Dr. Patrick Sullivan.

Figure 7. Densely-arranged, brown-pigmented cells with crystalline material form the cutaneous mass (left). Under polarized light, the cytoplasmic crystalline material is birefringent (right). Note these images are of the same field of view.

Iridophores represents a specific chromatophore type, with cytoplasmic crystalline structures that reflect light. Chromatophores are pigment-containing cells present in reptiles, amphibians, and fish, contributing to these animals’ unique coloration (and, in some instances, color-changing abilities). Tumors of pigmented cells (chromatophoromas) have been reported in amphibians7, reptiles8,9, and fish, although I could not find a published report specifically detailing iridophoroma in a frog.

The mass in the present case recurred locally, requiring a second excision. The owner reported the frog was doing well at last communication.

Summary

Cases that are “cool” to the pathologist may not always feel the same from the clinical perspective, as they may require aggressive treatment, may have less published data to guide therapy, or simply may have negative outcomes. But please note that three of the four cases shared here were alive at the last communication! I hope you found them as interesting and enjoyable as I did. Thank you to all the veterinarians who worked hard through the pandemic year and beyond to help animals like these.

References

- Aspergillosis in cats. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. Hartmann K, Lloret A, Pennisi MG, et al. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;15:605-10.

- Corneal and anterior segment foreign body trauma in dogs: a review of 218 cases. Tetas Pont R, Matas Riera M, Newton R, Donaldson D. Vet Ophthalmol. 2016;19:386-97.

- A case of fatal systemic toxoplasmosis in a cat being treated with cyclosporin A for feline atopy. Last RD, Suzuki Y, Manning T, et al. Vet Dermatol. 2004;15:194-8.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock in a cat with disseminated toxoplasmosis. Evans NA, Walker JM, Manchester AC, Bach JF. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2017;27:472-8.

- Antemortem diagnosis and treatment of toxoplasmosis in two cats on cyclosporin therapy. Barrs VR, Martin P, Beatty JA. Aust Vet J. 2006;84:30-5.

- A case of pulmonary toxoplasmosis resembling multiple lung metastases of nasal lymphoma in a cat receiving chemotherapy. Murakami M, Mori T, Takashima Y, et al. J Vet Med Sci. 2018;80:1881-6.

- Analysis of published amphibian neoplasia case reports. Hopewell E, Harrison SH, Posey R, et al. J Herpetol Med Surg 2020;30:148-55.

- Melanophoromas and iridophoromas in reptiles. Heckers KO, Aupperle H, Schmidt V, Pees M. J Comp Path 2012;146:258-68.

- Cutaneous chromatophoromas in captive snakes. Muñoz-Gutiérrez JF, Garner MM, Kiupel M. Vet Pathol 2016;53:1213-9.

- Chromatophoromas and chromatophore hyperplasia in Pacific rockfish (Sebastes spp.). Okihiro MS, Whipple JA, Groff JM, Hinton DE. Cancer Res 1993;53:1761-9.