-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Katherine Hogan, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology)

By Katherine Hogan, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology)

angell.org/cardiology

617-541-5038

INTRODUCTION

Subaortic stenosis (SAS) is one of the most common congenital heart defects in dogs. Retrospective studies suggest that SAS accounts for ~15-35% of congenital heart disease in dogs, and it is rare in cats. This disease primarily affects large breed dogs, with Golden Retrievers, Newfoundlands, Rottweilers, and Boxers more predisposed to SAS. A genetic basis has been established in Newfoundlands.

Subaortic stenosis occurs due to presence of a fibrous or fibromuscular ridge or ring of abnormal tissue below the aortic valves; this differs from the less commonly occurring aortic stenosis, in which there is abnormal development of the valve leaflets themselves. Subaortic stenosis causes obstruction to bloodflow exiting the left ventricle and ultimately left ventricular pressure overload, causing left ventricular concentric hypertrophy, ischemia, and fibrosis. Additionally, this can affect coronary bloodflow to the thickened ventricular walls, leading to ventricular arrhythmias.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Subaortic stenosis can be suspected based on signalment, history, and physical exam findings. Patients with mild or moderate SAS are often asymptomatic; however, patients with severe SAS are prone to showing signs of weakness, exercise intolerance, and potentially sudden death. Physical exam abnormalities can include left basilar systolic murmur, weak femoral pulses +/- a delayed peak (pulsus parvus et tardus), or presence of arrhythmias. The murmur of SAS can potentially be heard in the cervical region due to turbulent blood flow traveling up the carotid arteries. Since SAS has the potential to worsen in severity until the affected dog is full grown, the murmur intensity may increase over the first 1-1.5 years of life.

Diagnosis of SAS is definitively made via echocardiogram, though thoracic radiographs or ECG may also be helpful in the initial workup of patients with SAS. Thoracic radiographs may reveal post-stenotic dilation of the aorta and left ventricular +/- atrial enlargement. If severe enough, thoracic radiographs will also aid in diagnosis of congestive heart failure. ECG may be normal, show evidence of left heart enlargement (tall R wave, wide QRS) or ventricular arrhythmias. A 24-hour Holter monitor can be used to further evaluate frequency and severity of ventricular arrhythmias and determine if anti-arrhythmic medications are necessary.

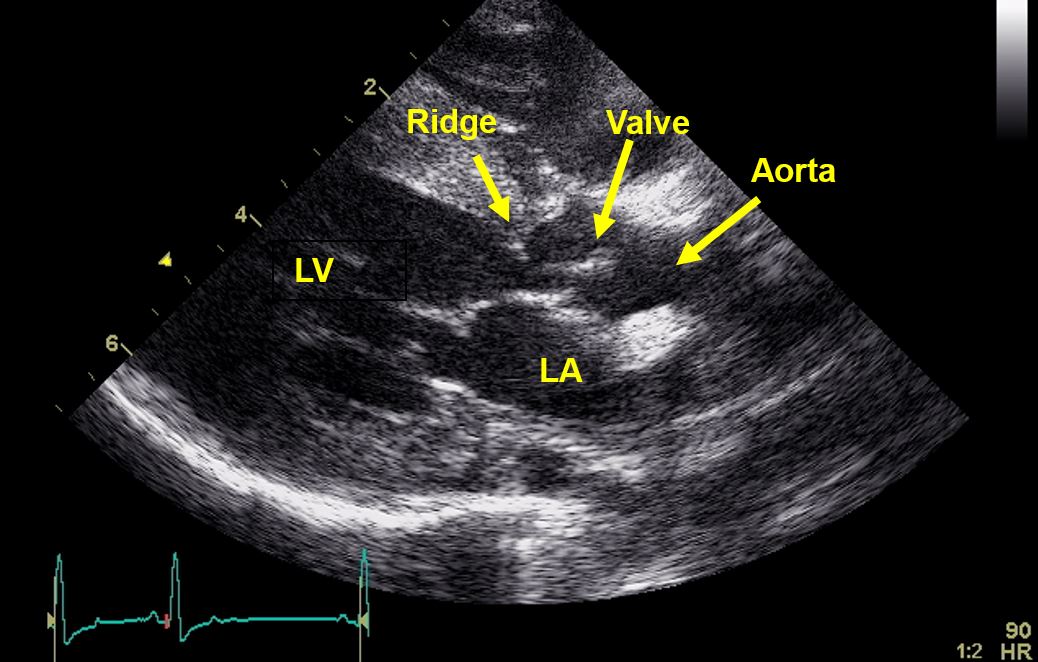

Echocardiogram of SAS will reveal a hyperechoic ridge or ring of tissue below the aortic valve leaflets. There may also be evidence of post-stenotic dilation of the aorta, left ventricular hypertrophy, or left atrial enlargement. Color Doppler will reveal turbulent blood flow starting at the level of the stenosis. Severity of SAS is determined based on the velocity across the stenotic region, which can be correlated to the pressure gradient (PG) between the left ventricle and aorta. Normal pressure gradient should be less than 20 mmHg; mild SAS 20-50 mmHg; moderate 50-80 mmHg; severe is considered greater than 80 mmHg, with some patients having pressure gradients as high as 250 mmHg!

Figure 1. Echo image (right parasternal long axis view focused over the left ventricular outflow tract) depicting a discrete hyperechoic ridge of tissue below the aortic valve leaflets. LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Subaortic stenosis is a condition that is most commonly treated via medical management. Beta-blocker therapy (e.g. atenolol or sotalol) is often initiated to try to alleviate symptoms and decrease myocardial oxygen demand. There are variable reports regarding the longterm benefit of beta-blocker therapy alone, but most cardiologists would recommend starting beta-blocker therapy in dogs with severe SAS. Even when mild, patients with SAS are at higher risk of developing infective endocarditis; thus, broad-spectrum antibiotics are often indicated when dogs require invasive surgery (GI surgery, aggressive dental cleaning with extractions, wound repair, etc.) or experience infections such as wounds or urinary tract infections (UTIs).

Development of surgical or minimally invasive techniques for treatment of SAS is an ongoing goal within veterinary medicine. Surgical treatment involves cardiac bypass to allow direct access for removal of the fibrous/fibromuscular tissue causing stenosis. This approach has been attempted in dogs, but it did not improve overall survival. Standard balloon dilation has also been attempted on dogs with severe SAS, but the reduction in PG was only transient and did not significantly extend survival in comparison to dogs treated only with atenolol. A minimally invasive technique involving a cutting balloon followed by standard balloon valvuloplasty has been developed for treatment of severe cases of SAS. Initial reports indicate that this procedure results in a significant decrease in PG and helps reduce symptoms of SAS, but re-stenosis often occurs over time. The overall effect of this procedure on survival times has not yet been determined. Typically this procedure is reserved for symptomatic patients or patients whose disease is considered very advanced, as this patient population may ultimately benefit due to reduction in symptoms.

PROGNOSIS

Prognosis for patients with mild or moderate SAS is generally good, with many having a normal lifespan and rarely exhibiting clinical signs. Patients with severe SAS often have a poor longterm prognosis, due to progressive symptoms. It has been estimated that ~70% of patients with severe SAS live less than 3 years. A recent study determined that even equivocally affected dogs with SAS could produce affected puppies even when bred to dogs considered normal. Given these findings, even mildly affected dogs should be excluded from the breeding pool.

REFERENCES

- Schrope, D. (2015). Prevalence of congenital heart disease in 76,301 mixed-breed dogs and 57,025 mixed-breed cats. Journal of Veterinary Cardiology, 17(3);192–202

- Bonagura JD, Lehmkuhl LB. (1999) Congenital Heart Disease. In: Textbook of canine and feline cardiology, principles and clinical practice. 2nd edn. Eds PR Fox, D Sisson, and NS Moise. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia. pp 471–535.

- Kienle R, Thomas W, Pion P. The natural clinical history of canine congenital subaortic stenosis. J Vet Intern Med 1994 November-December;8(6):423-431

- Stern JA, White SN, Lehmkuhl LB, et al. A single codon insertion in PICALM is associated with development of familial subvalvular aortic stenosis in Newfoundland dogs. Human Genetics, 133(9);1139-1148.

- Orton EC, Herndon GD, Boon JA, Gaynor JS, Hackett TB, Monnet E. (2000). Influence of open surgical correction on intermediate-term outcome in dogs with subvalvular aortic stenosis: 44 cases (1991-1998). Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association, 216(3):364-7.

- Meurs KM, Lehmkuhl LB, Bonagura JD. (2005). Survival times in dogs with severe subvalvular aortic stenosis treated with balloon valvuloplasty or atenolol. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association, 227(3):420-4.

- Kleman, M., Estrada, A., Maisenbacher, H., Prošek, R., Pogue, B., Shih, A., & Paolillo, J. (2012). How to perform combined cutting balloon and high pressure balloon valvuloplasty for dogs with subaortic stenosis. Journal of Veterinary Cardiology, 14(2):351-61.

- Kleman ME, Estrada AH, Tschosik ML et al. An update on combined cutting balloon and high pressure balloon valvuloplasty for dogs with severe subaortic stenosis [abstract]. In: Proceedings of the 2013 ACVIM Forum, June 12-15; Seattle, WA. Abstract nr C-18.

- Eason, B. D., Fine, D. M., Leeder, Stauthammer, Lamb, & Tobias, A. H. (2014). Influence of Beta Blockers on Survival in Dogs with Severe Subaortic Stenosis. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 28(3);857-862.