-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Zachary Crouse, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM)

Zachary Crouse, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM)

angell.org/internalmedicine

internalmedicine@angell.org

617-541-5186

Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence (USMI) is the most common cause of acquired urinary incontinence in adult dogs.1,2 USMI can affect up to 20% of neutered female dogs,3 and is more common in large breed dogs.1 The urethral sphincter is composed of urethral smooth muscle, surrounding connective tissues, and vasculature.3 The pathophysiology of USMI is complex, and involves loss of estrogen receptors on the smooth muscle, as well as changes to collagen content and conformation of the patient (pelvic bladder, short urethra, recessed vulva).1,3 While loss of estrogen does not contribute to USMI in male dogs, hormones still appear to play a role in development of USMI in males, as USMI occurs more frequently in neutered male dogs than intact male dogs.3

Dogs with USMI typically leak urine when asleep or in lateral recumbency, but may also have urine leakage during excitement or activity.2 A thorough history, physical exam with attention to conformation of the urogenital tract, urinalysis, and culture are essential to exclude other causes of incontinence. A complete blood count and serum chemistry may be indicated, and further urogenital imaging (abdominal ultrasound, cystoscopy, or CT) may be necessary to exclude anatomic causes of incontinence.2,3 Dogs with USMI should have a compatible history and unremarkable lab work. Physical exam and imaging studies may show anatomic abnormalities contributing to USMI, such as a pelvic bladder or recessed vulva, but should exclude separate causes of incontinence, such as ectopic ureters.

After a diagnosis of USMI has been made, medical therapy is considered the first line of treatment. Estriol (Incurin, see package insert for dosing instructions) and diethylstilbestrol (DES, 0.1-1.0 mg/dog po q24 for 5-7 d then weekly or as needed) are estrogen compounds that can be used to increase the number and sensitivity of the estrogen receptors in the female dog’s urethral sphincter. Estriol is effective in 89% of cases of USMI, and DES is effective in 65% of cases. When using an estrogen compound, a CBC should be checked prior to starting treatment and after one month on the chosen drug, although bone marrow suppression is not listed as an expected adverse event of estriol’s daily administration.3 Currently, estriol is the only FDA-approved estrogen compound for treatment of USMI in dogs, and should be the first choice in female dogs suspected of having USMI. Phenylpropanolamine (PPA, 1.0-1.5 mg/kg po q8-12) is an alpha adrenergic agonist which increases the tone of the smooth muscle comprising the urethral sphincter2 and ranges in efficacy from 75-90%3. A combination of estrogen therapy with PPA is commonly used in dogs who do not respond to medical therapy with a single agent. While there is a lack of evidence to support a synergistic effect between PPA and estrogens, there are anecdotal reports of success when the therapies are combined.4 Estrogen compounds should not be used in male dogs and should be used with caution in cats.2 When USMI remains refractory to medical therapy with PPA (male dogs, cats) or a combination of PPA and an estrogen compound (female dogs), then use of a urethral bulking agent (UBA) or surgical intervention should be considered.

UBAs should be used in patients where additional lower urinary tract disease has been excluded and medical management has failed. These patients should have a negative culture within 2 weeks of injection of the UBA. With the use of a UBA, many dogs have improvement in incontinence for a period of 10-18 months, but may also require medical management during this time to maintain continence.4 UBAs are delivered cystoscopically by injecting the agent submucosally within the urethra. Currently, collagen is available in the United States for submucosal injection (Regain- Avalon Medical). Risks with injection of a UBA include infection, bleeding, urethral obstruction, failure of continence, and intolerance of the injected material.4 Prior to injection of a UBA, clients should be educated that expected continence rates are 50-70% with UBA and that medications and repeat procedures may be necessary as the UBA will have a limited duration of efficacy.4

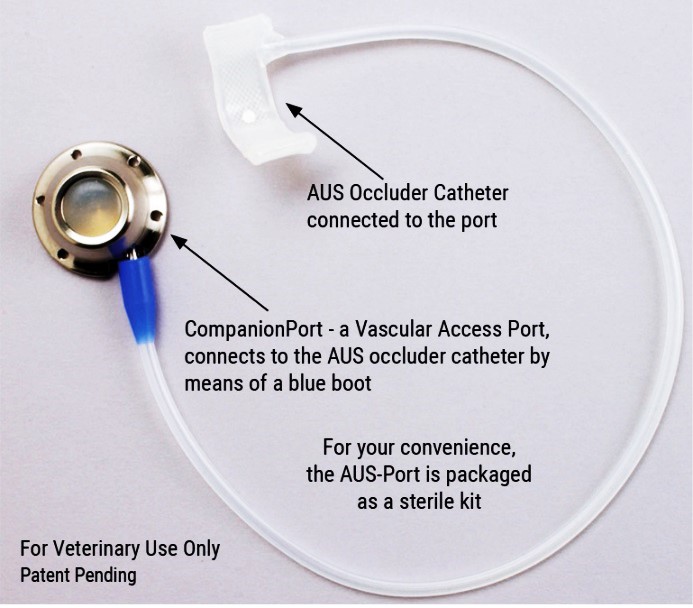

Numerous surgical options to correct USMI have been described but typically have poor long-term efficacy. More recently, placement of a urethral hydraulic occluder (HO) has shown promise. A urethral HO is comprised of an incomplete silicone ring that is sutured around the pelvic urethra. The silicone ring is inflatable and is connected to a small injection port that is sutured subcutaneously, to allow future access.5 After placement of the hydraulic occluder, many patients will require inflations to maximize continence. The protocol for inflation of the HO device is clinician dependent, but the goal is to incrementally increase the amount of saline in the occluder cuff until an acceptable level of urinary continence has been acheived. In one study of 18 female dogs with refractory urinary incontinence, all dogs had an improved continence score.5 In this same study, in dogs with owners who were compliant for follow up, 92% were functionally continent and 77% were completely continent.5 In addition to female dogs, placement of urethral HO devices has been described in male dogs6 and female cats.7

The vast majority of patients diagnosed with USMI will respond to either estriol, DES, or PPA. In cases of female dogs that are refractory to single agent medical therapy, use of both PPA and an estrogen drug should be attempted. If incontinence persists in these cases, then use of a UBA or surgical implantation of a urethral HO device can improve continence and quality of life.

References

- Byron JK, Taylor KH, Phillips GS, and Stahl MS. Urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence in 163 neutered female dogs: diagnosis treatment, and relationship of weight and age at neuter to development of disease. J Vet Intern Med 2017; 31:442-448.

- Owen LJ. Ureteral ectopia and urethral sphincter mechanism incompetence: an update on diagnosis and management options. J Small Anim Pract. 2018. Epub ahead of print.

- Byron JK. Micturition disorders. Vet Clin Small Anim. 2015; 45: 769-782.

- Byron J. Injectable bulking agents for treatment of urinary incontinence. In: Veterinary image-guided interventions. 1st edn, Weisse C and Berent A eds, Wiley Blackwell, Ames, IA. 2015:398-409.

- Curao RL, Berent AC, Weisse C, and Fox P. Use of a percutaneously controlled urethral hydraulicoccluderfor treatment of refractory urinary incontinence in 18 female dogs. Vet Surg. 2013 May; 42(4):440-7.

- Reeves L, Adin C, McLoughlin M, et al. Outcome after placement of an artificial urethral sphincter in 27 dogs. Vet Surg. 2013; 42(1):12-8.

- Wilson KE, Berent AC, and Weisse CW. Use of a percutaneously controlled hydraulic occluder for treatment of refractory urinary incontinence in three female cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016 Mar; 248(5):544-51.