-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Dan Biros, DVM, DACVO

angell.org/eyes

ophthalmology@angell.org

617-541-5095

Along with eyelid margin tumor removals and entropion repair, the repair of a prolapsed third eyelid gland is among the top 5 most common procedures we perform in the Ophthalmology service at Angell-Boston. The principles of gland prolapse repair involve restoring the normal position of the gland while at the same time addressing the associated inflammation that can often affect the tear production and the final position of the gland after surgery and recovery. Third eyelid gland prolapse can happen at any age and in any breed but is far more prevalent in the brachycephalic dogs due to the relatively small size of the orbit and tight eyelid conformation that cannot accommodate an enlarged or inflamed nictitans gland. There does not appear to be a gender predisposition to the condition, and it can appear as a bilateral or unilateral change. Dogs with third eyelid gland prolapse are at elevated risk for dry eye, and if untreated can lead to chronic ocular surface irritation and secondary corneal disease through contact of the gland on the cornea from the exposed and often desiccated gland surface conjunctiva.

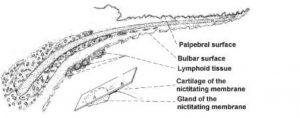

The third eyelid gland in dogs is a tubinoacinar seromucous accessory lacrimal gland that is located adjacent to and surrounding the nictitans cartilage (Figures 1 and 2)

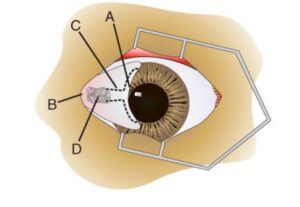

Figure 2 Canine Nictitans orientation: A) Leading edge. B) Base. C) T-shaped hyaline cartilage. D) Superficial gland of the nictitans. (Gelatt, 2011)

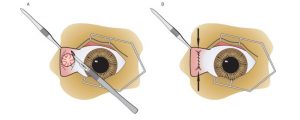

When the gland becomes inflamed it enlarges and protrudes out through the path of least resistance which is up and out from behind the nictitans typically towards the visual axis anterior to the cornea (Figure 3).

In some patients, the protrusion is large enough to cause some transient lagophthalmos and subsequent exposure keratitis. Causes for the gland protrusion are varied, and mostly involve some form of chronic (hereditary) inflammation that leads to gland enlargement, which not only dislocates the gland, but also stretches the elastic ligaments that normally hold the gland in place. Prolapsed glands often first appear intermittently, in young dogs less than 5 years of age, and often only in one eye at first. If the patient presents for acute prolapse, or the size of the gland is relatively small, manual repositioning of the gland is a feasible option with the aid of topical anesthesia and an instrument such as Von Graefe’s tissue forceps. If the gland can be repositioned successfully and tear production is normal or low, then subsequent treatment with topical anti-inflammatories can go to work reducing inflammation. We like to dispense neopolydex onto the affected eye 2-3 times daily with a follow-up of the patient in about 3-4 weeks. If tear production is low, then topical cyclosporine (e.g. optimmune) can also be used twice daily to reduce inflammation and promote better tear production. In the majority of patients whose gland is manually replaced, these glands reprolapse over time due to the structural change of the ligaments holding the gland and the persistence/progression of some degree of chronic active inflammation.

When gland prolapse is significant and lasting, manual replacement is not a suitable option, and surgical repair is often a more reasonable approach to restore normal gland position. Several options for gland repair are in the literature, and there is no one procedure that is universally superior to the others. As with any elective procedure, the keys to a successful surgery is familiarity and comfort with the procedure that works best for any given surgeon. The goal of care is to reposition the gland so it remains out of sight and can function as a tear producer supporting the ocular surface health (Figure 4).

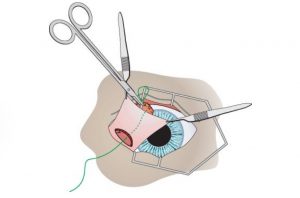

Most procedures in use today involve harnessing the prolapsed gland and securing it to a relatively immobile surface that will minimize the chance for reprolapse. The orbital tacking technique is one of those traditional methods (Figure 5). Non-absorbable suture (e.g. 4-0 Nylon) is used to anchor the gland to the orbital rim or periorbital tissue. This physically presses the gland to the base of the nictitans, and inferior orbit. By using non-absorbable suture, the procedure is designed to last for years as long as the anchoring suture holds.

Another popular way to repair the prolapsed gland, developed here at Angell decades ago by Dr. Rhea Morgan, is to create a supportive pocket for the gland, bringing it closer to the posterior surface of the nictitans by burying safely below the surface conjunctiva of the nictitans in a way that allows it to function (Figure 6). This procedure uses absorbable suture (e.g. 5-0 or 6-0 vicryl) to create a soft tissue pocket that will hold the gland and naturally adhere to the gland so it remains in place below the surface of the posterior conjunctiva of the nictitans. This procedure relies on scar tissue formation within the pocket to hold the gland in place long after the suture dissolves.

Modifications of the described techniques can be used to the surgeon’s preference. For example, in some brachycephalic breeds, namely English bulldogs, I use a combination orbital tacking and pocket technique due to elevated rates of gland prolapse recurrence in this breed. Other techniques are in the literature, including on a relatively new method created by Dr. John Sapienza which secures the gland via suture to the inferior rectus muscle as well as variation techniques on the pocketing and tacking of the gland. Full resection of the gland is to be avoided if at all possible since the gland provides vital surface moisture to the ocular surface. Removing the gland should be reserved only for cases of gland neoplasia or severe trauma to the gland where it is no longer viable, for example if the tissue is necrotic or avulsed from the majority of its attachments. These conditions are extremely rare. In other rare cases where there is ongoing but significant partial reprolapse following multiple surgeries I have partially amputated the glands that are persistently prolapsed, but I emphasize that these situations are extremely rare, and in all cases, we strive to preserve the gland in situ if possible. There are a few cases we have managed over the years who arrive to us with prolapsed gland removal at a young age. These patients almost without exception have chronically dry eyes with corneal and conjunctival damage affecting comfort and vision.

While surgery is a primary part of the solution to prolapsed nictitans, medical therapy is the other integral part to ensure a successful outcome. After surgery it is routine for us to use both topical and systemic medication to manage inflammation and support the tear production. Any topical steroid is stopped for at least 2-4 weeks after surgery as the surgery site heals. An E-collar is used in patients at risk for rubbing at the eye or with chronic inflammation that is significant, and in most brachycephalics. In routine third eyelid gland prolapse repairs with minimal pre-existing inflammation, we do not use E-collars postoperatively. Oral NSAIDs and topical antibiotics are commonly used for a minimum of two weeks, but often a longer course is needed for patients with significant dryness or preexisting inflammation. Our usual follow-up plan is to see the patient 10-14 days after surgery and again one month after that, then as needed. For patients who get the periorbital tacking technique, there is one skin suture on the skin below the eye that will be removed at that time. I remind clients that their pet remains on watch for dry eye so annual tear level check should be performed at a minimum. In patients with chronic skin infections especially in the face or facial folds, it is not uncommon to use oral antibiotics for 7-10 days to ensure the best possible healing. Chronic complications from the surgery are rare but generally considered to include chronic or persistent inflammation, reprolapse of the gland, corneal ulceration or infection, or suture reaction. Following surgery, the posterior surface of the third eyelid is often decreased, and the third eyelid is often less mobile, but overall function and cosmetic appearance is generally very good. In some cases of periorbital tacking the lower eyelid is pulled down slightly but the overall function remains fine.

In summary, third eyelid gland prolapse is a common adnexal disorder in dogs. There are several options for surgical replacement. Removal of a prolapsed gland is not advised unless there is a concern for cancer. Concurrent medical treatment is an integral part of pre and post op care. Dogs with a history of third eyelid gland prolapse should be monitored throughout their lives for dry eye.

For more information about Angell’s Ophthalmology service, please visit angell.org/eyes. Dr. Biros can be reached for consults or referrals at 617-541-5095 or ophthalmology@angell.org

References

Gelatt K.N. & Gelatt J.P. (2011) Veterinary Ophthalmic Surgery. Edinburgh: Elsevier-Saunders, 157-190.

Moore CP, Constantinescu GM. Surgery of the adnexa. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1997 Sep; 27(5):1011-66.

Dugan SJ, Severin GA, Hungerford LL, Whiteley HE, Roberts SM. Clinical and histologic evaluation of the prolapsed third eyelid gland in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992 Dec 15; 201(12):1861-7.

Sapienza JS, Mayordomo A, Beyer AM. Suture anchor placement technique around the insertion of the ventral rectus muscle for the replacement of the prolapsed gland of the third eyelid in dogs: 100 dogs Vet Ophthalmol 2014 Mar;17(2):81-6

Stanley RG, Kaswan RL. Modification of the orbital rim anchorage method for surgical replacement of the gland of the third eyelid in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994 Nov 15; 205(10):1412-4.

Plummer CE, Källberg ME, Gelatt KN, Gelatt JP, Barrie KP, Brooks DE. .Intranictitans tacking for replacement of prolapsed gland of the third eyelid in dogs. Vet Ophthalmol. 2008 Jul-Aug; 11(4):228-33.

Prémont JE, Monclin S, Farnir F, Grauwels M. Perilimbal pocket technique for surgical repositioning of prolapsed nictitans gland in dogs. Vet Rec. 2012 Sep 8; 171(10):247.