-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Kristine Burgess, DVM, MS, DACVIM (MedicalOncology)

By Kristine Burgess, DVM, MS, DACVIM (MedicalOncology)![]()

angell.org/oncology

oncology@angell.org

617-541-5136

May 2022

Tumors of the bladder and urethra account for approximately 0.5-1.0% of all canine neoplasms. Most bladder tumors are malignant, and 75 to 90% of primary urinary bladder epithelial tumors are transitional cell carcinomas (TCC). Female dogs outnumber males by approximately 2:1, and neutered animals of either gender have approximately four

bladder tumors are malignant, and 75 to 90% of primary urinary bladder epithelial tumors are transitional cell carcinomas (TCC). Female dogs outnumber males by approximately 2:1, and neutered animals of either gender have approximately four  times the risk of their intact counterparts. A breed predistribution has been firmly established with Scottish Terriers, West Highland White Terriers, Shetland Sheepdogs, Beagles, and other terrier breeds being of higher risk.

times the risk of their intact counterparts. A breed predistribution has been firmly established with Scottish Terriers, West Highland White Terriers, Shetland Sheepdogs, Beagles, and other terrier breeds being of higher risk.

Pesticide exposures are a recognized environmental risk factor for TCC in dogs. While the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide and environmental tobacco exposures are risk factors for TCC in humans, a cause-and-effect relationship has not been established in dogs. Diet and body condition have also been evaluated as risk factors for the development of TCC, with overweight animals having three times increased risk compared to lean dogs.

condition have also been evaluated as risk factors for the development of TCC, with overweight animals having three times increased risk compared to lean dogs.

Clinical Signs and Physical Examination Findings

Most commonly, dogs with undiagnosed TCC will present to your veterinary hospital with lower urinary tract signs indistinguishable from those observed with urolithiasis or lower urinary tract infection and may include stranguria and hematuria pollakiuria, and tenesmus. Because this cancer has a predilection for the bladder trigone, it is not unusual for dogs to have an unremarkable physical examination. As a result, TCC is often diagnosed late in the disease process, as many dogs can have a transient response to empiric antibiotic therapy or anti-inflammatory medications. A delayed diagnosis can be incredibly frustrating to a clinician and the pet owner and will be a detriment to the patient as the cancer is allowed to progress without treatment. Thankfully, newer, non-invasive diagnostic tests are now available to assist the clinician in establishing a definitive diagnosis. One of these tests described below can be used as a screening aid for dogs at high risk for developing this cancer (e.g., Terriers, Beagles, etc.)

Diagnostic Tests

Identifying BRAF mutations in dogs with urothelial carcinomas has revolutionized the ability to diagnose a historically challenging cancer. Previously utilized non-invasive diagnostics have included a urinalysis with a cytologic evaluation of the sample. However, this is confounded by a pleomorphic appearance of reactive hyperplastic transitional cells that can be indistinguishable from malignant cells and is not recommended. This new diagnostic test relies on the molecular detection of a genetic alteration of the BRAF gene present in voided urine. This commercially available test (Cadet BRAF test) can successfully detect cancer in ~80% of dogs with bladder or prostate cancer.

Another commercially available bladder tumor antigen (BTA) test can support a diagnosis of TCC, although false-positive results can be obtained when there is significant proteinuria, glucosuria, pyuria, or hematuria. Given the potential for false-positive results, this test may be more appropriately used to screen at-risk populations with a 93% negative predictive value and 27% positive predictive value in this setting.

Another commercially available bladder tumor antigen (BTA) test can support a diagnosis of TCC, although false-positive results can be obtained when there is significant proteinuria, glucosuria, pyuria, or hematuria. Given the potential for false-positive results, this test may be more appropriately used to screen at-risk populations with a 93% negative predictive value and 27% positive predictive value in this setting.

While abdominal ultrasonography (AUS) is the most relied upon imaging tool to evaluate the bladder, urethra, and prostate, TCCs can have a wide variety of appearances on abdominal ultrasound, which overlaps those of other tumors, benign polyps, cystitis, and urethritis. Therefore, a definitive diagnosis of TCC cannot be made on ultrasonographic appearance alone. While a histopathological evaluation of a tumor biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of TCC, obtaining a BRAF+ test with confirmed urothelial mass noted on ultrasound examination can be sufficient to initiate treatment. Nevertheless, if biopsies are deemed necessary, they should be obtained via traumatic catheterization, cystoscopy, or an open surgical biopsy. Care must be taken with any disruption of a bladder, prostate, or urethral mass due to the potential for abdominal seeding.

Cystoscopy allows visual inspection of the entire urethral lining, the trigone area, the ureteral orifices, and the bladder lining. Cystoscopy also allows the collection of pinch biopsies for histologic evaluation. However, like the tests mentioned above, the appearance of lesions observed cystoscopically is not diagnostic for TCC as benign tumors and proliferative urethritis/cystitis can have a similar appearance

Staging

TCC staging includes routine bloodwork and urinalysis as a minimum database. Urine culture is often indicated as secondary infections are common. Thoracic radiographs are essential to evaluate for metastasis to the lungs. Caution is advised when interpreting thoracic radiographs as lung metastasis from TCC can appear as unstructured interstitial opacities, which may be incorrectly interpreted as normal aging change. An abdominal ultrasound will provide information regarding disease spread to intra-abdominal lymph nodes or other organs.

Prognosis

Several factors have been tested for their impact on prognosis. The most consistent variables strongly associated with decreased survival include lymph node involvement, the presence of distant metastasis, and high-grade tumors with high mitotic index +/- vascular invasion.

Treatment Options

Most TCC tumors overexpress surface COX-2 receptors, so COX-2 inhibitory nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the mainstay treatment. In dogs with TCC treated with a COX-2 inhibitory NSAID alone, disease stabilization was noted in 53%, partial responses in 12%, and complete responses in 6%. Piroxicam is the best-studied NSAID for use in dogs with TCC, but similar results have been reported with more COX-2 selective and, therefore, safer drugs, including deracoxib and meloxicam. Carprofen is not considered highly selective for COX-2 and is not recommended to treat canine TCC.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy has been variably successful, with most dogs receiving a series of chemotherapy agents with no clear roadmap regarding which agent will be most effective for an individual patient. Currently, many oncologists will start with a course of the chemotherapy drug vinblastine and, if effective, continue that treatment until progressive disease has been noted on AUS or there has been a recrudescence of clinical symptoms. Other chemotherapy drugs considered to have efficacy in TCC include doxorubicin, cisplatin, carboplatin mitoxantrone, toceranib, and metronomic or continuous low-dose chlorambucil. Given the lack of standard treatment recommendations and the variable success of chemotherapy in treating TCC, the evaluation of different drugs or drug combinations is an area of active research.

Radiation Therapy

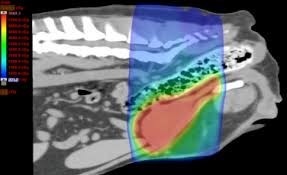

Previously radiation therapy was discouraged as a treatment for canine TCC based on concerns for considerable morbidity related to late radiation therapy side effects, including intestinal stricture formation and bladder fibrosis. However, newer radiation therapy treatment modalities such as IMRT allow for more targeted or conformal delivery of radiation treatment, thereby sparing normal tissue in the area. Several recent studies in the veterinary literature have demonstrated excellent tumor control utilizing radiation therapy in the gross disease setting for dogs with TCC of the bladder, urethra, and prostate. Overall, the treatment was well tolerated, with objective and subjective responses achieved.

Based on this, radiation therapy is now recommended as a safe and effective modality in treating canine TCC. With more studies in the veterinary literature, this treatment modality will likely become the standard of care for canine TCC and primary prostatic neoplasia. The recommended treatment approach will likely include radiation therapy as a first-line treatment to address bulky disease and the addition of chemotherapy to prevent distant or metastatic disease.

and effective modality in treating canine TCC. With more studies in the veterinary literature, this treatment modality will likely become the standard of care for canine TCC and primary prostatic neoplasia. The recommended treatment approach will likely include radiation therapy as a first-line treatment to address bulky disease and the addition of chemotherapy to prevent distant or metastatic disease.

Surgery

Because of the trigonal location of the majority of TCCs and the invasive nature of this cancer, surgical excision with complete histopathologic margins is not achievable. Additionally, TCC may be present in multifocal lesions in the bladder due to the “field effect,” and implantation of tumor cells at the surgical incisions has also been observed. Therefore surgical treatment for TCC is generally not recommended. Indwelling, low-profile cystotomy catheters have been utilized for palliative measures to relieve urethral obstructions.

Palliative Therapies

Laser ablation of the tumor tissue as a debulking procedure can result in rapid clinical improvement. Reported complications included stranguria, hematuria, urethral stenosis, cystitis, local tumor seeding, and urethral perforation.

Stents can also be placed into canine ureters and urethras, and the application of this technique has been recently reviewed. In one study of 12 severely obstructed dogs with urethral tumors, two-thirds were considered to have a good to excellent outcome with stent placement. Most dogs were continent after the procedure, but 17% became severely incontinent. However, survival after the procedure was short, with a median of only 20 days. Earlier intervention may improve post-procedure outcomes.

Due to the relatively high complication rate with either stent placement or laser ablation, these procedures are recommended for those clinicians with experience in these techniques.

Feline TCC

Approximately 60% of primary bladder cancer in the cat is TCC, which has also been reported in the feline kidney. The anatomic distribution of bladder TCC is different in cats than dogs, with the non-trigonal bladder wall being affected in 55% of cases. Based on minimal studies in the veterinary literature, feline TCC tumor characteristics and survival times are comparable to those reported in the dog, although based on anecdotal experience, the feline may be more aggressive in metastatic behavior, and response to chemotherapy/radiation therapy is widely variable. Consequently, surgical options may be more beneficial in this species.

Comparative Aspects of TCC

Future treatments for dogs with TCC include the development of BRAF inhibitors as targeted treatment of BRAF mutant tumors. Targeted therapies have proven highly effective in several human malignancies harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Success in this area would underscore the power of individualized medicine in canine tumors laying the groundwork for future areas of study in other tumor types.