-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Patty J. Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (Anatomic and Clinical Pathology)

Patty J. Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (Anatomic and Clinical Pathology)

www.angell.org/lab

pathology@angell.org

617 541-5014

When fatty tumors are mentioned, lipoma is typically what comes to mind. However, there is another, less common fatty tumor-like mass known as xanthoma that should be considered, especially when evaluating birds with one or more skin masses. In this brief article, xanthomas in birds, cats and dogs will be reviewed with a special focus on the use of cytology and histopathology to diagnose this unique entity.

Figure 1: Photograph of a subcutaneous xanthoma excised from the left tibiotarsal region of an 11 year old male Monk parakeet (Quaker parrot). In this cross section of an oval, smoothly contoured mass, note the bright yellow color and small foci of red-tan mottling representing areas of hemorrhage and necrosis (black arrows). Photo courtesy of Dr. Pam Mouser, Angell Pathology

Xanthomas (also known as xanthomatosis or xanthogranuloma) appear as discrete yellow nodules, plaques or thickenings in the skin (Figure 1) that can increase in size over time and be locally invasive. The non-neoplastic masses are composed of cholesterol, cholesterol esters and other lipids that induce a granulomatous inflammatory reaction at one of more sites. Xanthomas have been reported in psittacine and gallinaceous birds with single case reports in a goose, American kestrel, and a great white pelican. They are relatively common skin masses in cockatiels and female budgerigars. In addition to birds, xanthomas have been described in humans, cats, dogs, horses, amphibians and reptiles. The most common cutaneous sites observed in birds are wings, dorsal cervical region, sternum, back, ventral abdomen and uropygial area. Although they are most frequently observed in the skin, they have also been reported in the conjunctiva, internal structures of the eye, oral cavity, internal organs, tendons/periarticular regions, and remote sites such as bone marrow. In cats, they most often occur in periocular and periorbital regions, legs, trunk or footpads, while in dogs, they typically occur on the face, ears, and ventrum.

The cause of xanthoma formation is not definitively known; however, some predisposing factors are shown in Table 1. Solitary cutaneous xanthomas are often idiopathic. When solitary or multiple cutaneous xanthomas (“xanthomatosis”) are identified in animals, evaluation of the diet for high fat content (especially seed-based diets in birds) and determination of serum cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations are indicated. Cutaneous xanthomas have been reported in cats with primary idiopathic familial hypertriglyceridemia and secondary hyperlipidemia due to diabetes mellitus, glucocorticoid therapy or progesterone therapy. Xanthomas have been experimentally induced in quails and mice deficient in either apolipoprotein E21 or low-density lipoprotein receptors when fed a diet high in cholesterol. In dogs, cutaneous xanthomas have been reported with hyperlipidemia secondary to diabetes mellitus and idiopathic hyperlipidemia.

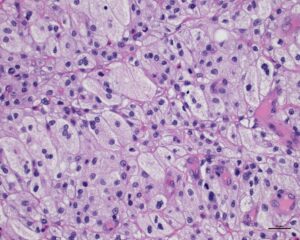

Figure 2: Photomicrograph of a histologic section of an oral cavity xanthoma that was surgically excised from a cat. Note sheets of foamy (lipid-laden) macrophages (thin black arrows) and fewer lipid-laden multinucleated giant cells (thick black arrows). H&E stain. Photo courtesy of Dr. Pam Mouser, Angell Pathology

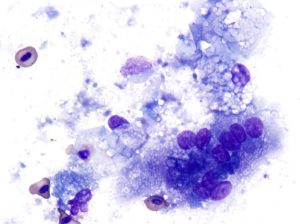

Definitive diagnosis of xanthoma requires histopathology. The masses appear histologically as sheets of foamy macrophages and fewer multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2) interspersed with cholesterol and lipid deposits. Histologic differential diagnosis includes granulomatous inflammation due to infectious etiologies, especially mycobacteriosis. For this reason, special stains and/or molecular diagnostics to exclude fungal and mycobacterial organisms as a cause of the inflammation are generally recommended. Fine needle aspiration for cytologic evaluation is a useful non-invasive method of obtaining a presumptive diagnosis of xanthoma/xanthomatosis. An example of cytologic features typical of a xanthoma is shown in figure 3. The predominant cell type found in cytologic specimens is finely vacuolated (foamy or lipid-laden) macrophages. Multinucleated giant cells and low numbers of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells may also be present. The background often has cholesterol crystals and round, clear areas typical of fat droplets. Cholesterol crystals are non-staining (clear) or pale basophilic staining angular, notched plates which may occur singly or in stacks or clusters.

Figure 3: Photomicrograph of a fine needle aspirate from a subcutaneous mass on the wing of female green-winged macaw. Note lipogranulomatous inflammation consisting of lipid-laden macrophages (thin black arrows), multinucleated giant cell (thick black arrow), and a heterophil (red arrow). Angular plates representing cholesterol crystals (green arrows) and clear vacuoles representing free lipid are present in the background. 1000x magnification, Wright-Giemsa stain

The treatment of choice for solitary cutaneous or oral xanthomas that are ulcerated, infected or large enough to interfere with function is surgical excision. Incomplete excision can lead to recurrence or poor wound healing. In some cases, the extent of tissue involvement and/or the location of the mass may preclude surgical excision. Cautery to control hemorrhage and use of an Elizabethan collar to prevent self-mutilation in birds may be helpful. Smaller, solitary quiescent xanthomas that are not bothering the bird are frequently not excised and just monitored periodically for increase in size. Prior to surgery and especially when multiple xanthomas are present, evaluation for underling dietary, metabolic, toxic and endocrinologic disorders is warranted. Treatment of predisposing conditions including dietary modification may improve xanthomatosis.

| Table 1. Predisposing Conditions To Consider For Xanthoma Formation |

| Hypercholesteremia/hyperlipidemia caused by:

– High-fat diet |

| Prior tissue necrosis at the site |

| Prior hemorrhage due to trauma or feather cyst removal |

| Exposure to toxic fat-soluble substances (example: chlorinated hydrocarbons) |

| Underlying cysts, lipomas or other tumors |

References:

- Schmidt RE, at al. 2003. Lymphatic and Hematopoietic System. In Schmidt RE, Reavill DR, Phalen DN, eds. Pathology of Pet and Aviary Birds. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing, p. 145.

- Campbell TW, et al. 2007. Comparative Cytology. In Campbell TW and Ellis DK, eds. Avian and Exotic Animal Hematology and Cytology, 3rd Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 193-195.

- Petrak ML and Glimore CE 1982. In Petrak ML, Ed. Diseases of Cage and Aviary Birds, 2nd edition. London: Lea & Febiger, pp.610-611.

- Di Girolamo N. et al. Subcutaneous xanthomatosis in a great white pelican. J Zoo Wildl Med 2014 Mar; 45(1): 153-6.

- Jaensch SM, et al. Atypical multiple, papilliform, xanthomatous, cutaneous in a goose (Anser anser). Aust Vet J. 2002 May;80(5):277-80.

- Haley PJ, Norrdin RW. Periarticular xanthomatosis in an American kestrel. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1982 Dec 1; 181(11): 1394-6.

- Hoekstra KA, et al. Dietary cholesterol-induced xanthomatosis in atherosclerosis-susceptible Japanese quail (Cotunix japonica). J Comp Pathol 1998 Nov; 119(4):419-27.

- Gumbrell RC. A case of multiple xanthomatosis and diabetes mellitus is a dog. N Z Vet J. 1972 Dec;20(12):240-2.

- Benajee KH, et al. Idiopathic solitary cutaneous xanthoma in a dog. Vet Clin Pathol 2011 Mar;40(1):95-8.

- Chanut F. et al. Systemic xanthomatosis associated with hyperchylomicronaemia in a cat. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 2005 Aug;52(6):272-4.