-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Daniela Vrabelova Ackley DACVIM

By Daniela Vrabelova Ackley DACVIM

angell.org/internalmedicine

MSPCA-Angell West

781-902-8400

This consensus was prepared by a group of experts in veterinary gastroenterology to bring us some guidelines for the use of commonly prescribed gastric acid protectants based on current evidence. This article describes how noxious agents cause gastric mucosal injury, the mechanisms of action of gastric acid protectants and their side effects, and indications for their use.

H2RAs (histamine-2 receptor antagonists) and PPIs (proton pump inhibitors) are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the US. Both are extensively overprescribed in human and veterinary medicine. This consensus calls for a judicious use of these medications considering recent studies that have documented adverse effects of long-term use.

The development of miniature pH measuring capsules in recent years has advanced our understanding of acid suppressant efficacy in animals and humans (Pic. 1). For the first time, no catheter is needed as the capsule sends a radiotelemetric signal to a receiving device. Unlike digital probes, capsules allow direct adherence to gastric mucosa with direct measurement of intragastric pH. Gastric pH is comparable in dogs, cats, and humans, and is used as a marker for gastroprotection.

The most common noxious factors impairing gastric mucosal barrier function in people are NSAIDs, stress, and Helicobacter pylori (HP). As many as 25% of people on chronic NSAID therapy develop GI ulcers and 2-4% will bleed or perforate. One veterinary study evaluating side effects of long-term NSAID therapy detected gastric lesions in all dogs treated with etodolac, ketoprofen, and flunixin, and in 1 in 6 dogs treated with carprofen. Stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD) is thought to result from local ischemia and occurs in critically ill patients. Approximately 75-100% of critically ill human patients have diffuse gastric hemorrhage and erosions visible on endoscopy. While HP is clearly connected with development of gastrointestinal (GI) ulcers in people, its role in dogs and cats remains uncertain.

DRUGS

Acid suppressant drugs, which inhibit acid production, have largely replaced acid-neutralizing drugs (antacids) as the drugs of choice for acid-related tissue injury. Therefore, we will focus on acid suppressant drugs.

Histamine-2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs)

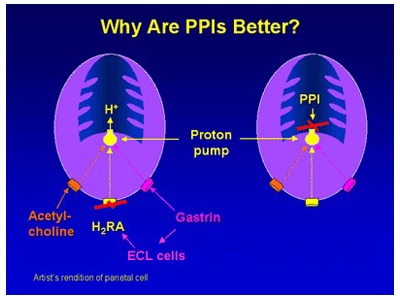

Picture 2: Comparison of mechanism of action between H2RAs and PPIs. Medscape, Paul W. Jungnickel PhD RPh , 10.16.2018

H2RAs (i.e., cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, nizatadine) competitively block only histamine type-2 receptors on the parietal cell (Pic. 2).

Based on studies, H2RAs have no to modest effect in decreasing gastric acidity depending on their dose. Ranitidine has minimal to no detectable effect in both dogs and cats. No significant differences were found between higher doses of famotidine (1-1.3mg/kg BID) and placebo in one small study investigating gastric pH over 96hrs in 6 dogs. Another study found famotidine (1mg/kg SID) more efficacious in reducing gastric lesions in sled dogs compared with no treatment. Several studies have demonstrated that H2RAs are inferior to PPIs for raising intragastric pH, as well as for prevention of exercise-induced gastritis in dogs. The situation is similar in cats; famotidine (0.9-1.3mg/kg BID) was found to be more efficacious than placebo but inferior to omeprazole in decreasing gastric acid production.

Recent studies in dogs and cats showed interesting findings of pharmacological tolerance or tachyphylaxis with continuous H2RA administration for 13 days and even as early as 3 days (!) in dogs and cats. Administration of famotidine q48hrs was shown to prevent tolerance. Abrupt discontinuation of H2RAs causes rebound acid hypersecretion in humans (and likely also in dogs and cats) as a result of the stimulating properties of gastrin on enterochromaffin cells.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

PPIs (omeprazole, pantoprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole) act by irreversibly blocking the proton pump (H+/K+ ATPase) of the parietal cell, which is responsible for secreting H+ ions into the gastric lumen (Pic. 2). Meta-analyses demonstrate that PPIs are significantly more effective than H2RAs in increasing gastric pH and preventing and healing acid-related tissue injury in people. There is a delay in their effect and on day 1 we see only 30% of acid inhibition with maximal effect achieved in 2-4 days. PPIs are acid-labile drugs susceptible to degradation by gastric acid before they reach the intestine where they are absorbed systemically. Gastric acid secretion is activated by ingestion of a meal. Therefore, it is recommended to administer PPIs 30-60min prior to a meal and if given once daily, morning administration is recommended. Several studies have suggested that omeprazole should be administered twice daily to achieve pH goals established for the treatment of acid-related disorders in people. In one study, no benefit was detected in increasing gastric pH when famotidine was administered concurrently with IV pantoprazole. To avoid rebound gastric acid hypersecretion, PPIs should be gradually tapered after administration for ≥ 4 weeks by 50% per week with cessation of evening dosing during the first week.

Table 1. Lists potential side effects linked to chronic PPI use in multiple retrospective human studies. However, these studies have significant limitations and did not demonstrate cause and effect. Very few adverse effects of PPIs have been noted in veterinary literature, with diarrhea being reported most frequently in dogs, but less commonly in cats.

Tab. 1

| Adverse effects related to PPIs in human literature |

|

Acute interstitial nephritis |

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is an important consideration in patients on chronic PPI therapy with increased numbers of gram-negative bacteria, and this could also increase the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Increased survival of swallowed bacteria is not only due to decreased gastric acidity but also due to other effects of PPI, including decreased intestinal peristalsis, decreased gastric emptying, changes in mucus composition, and increased bacterial translocation.

Sucralfate

Sucralfate is a basic aluminum salt of sulfated disaccharide that forms complexes with positively charged proteins in damaged mucosa, protecting them from pepsin. Human studies comparing sucralfate to H2RAs demonstrated equal efficacy in treating low-grade reflux esophagitis. More severe cases did not respond well. When sucralfate is compared to placebo, there is conflicting data regarding its therapeutic benefit. The relative ineffectiveness of sucralfate could be due to limited retention in esophagus (sucralfate stays in the esophagus for 3hrs in <50% of patients) and its need for an acidic environment to function (sucralfate is rapidly cleared from a nonacidified esophagus).

Many animals are administered PPIs, H2RAs, and sucralfate concurrently; however, there is increasing evidence that this practice will blunt the efficacy of PPIs and sucralfate, unless dosing is separated by at least 2 hours.

Misoprostol

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue binding prostaglandin receptors and exerting multiple cytoprotective effects. In several veterinary studies, misoprostol was effective in decreasing gastric ulceration in dogs receiving aspirin, but not methylprednisolone. Usefulness of this drug is limited by its GI side effects (abdominal pain and diarrhea). A panel of experts has concurred that misoprostol should primarily be considered as a prophylaxis for NSAID therapy only if PPIs fail or cannot be used.

EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT USE OF GASTROPROTECTANTS IN DOGS AND CATS

Gastritis

It is noteworthy to mention that no study has confirmed the benefit of gastric acid suppression in cases of idiopathic gastritis to date, even though gastric acid suppressants are used extensively in these patients. Acid suppression with famotidine (0.5 mg/kg SID) did not affect the frequency of clinical signs in 23 dogs with histologic evidence of gastritis and spiral bacteria in gastric mucosal biopsy samples.

Hepatic disease

Liver disease can lead to gastrointestinal ulceration due to altered mucosal blood flow caused by portal hypertension or hyperacidity due to decreased gastrin clearance by liver. A recent study looking at dogs treated for intrahepatic shunts demonstrated substantial reduction in deaths due to GI bleeding in dogs that received peri- and post-surgical life-long PPI therapy. PPIs may indirectly stop gastric bleeding by raising gastric pH and stabilizing blood clots.

SRMD (Stress-related Mucosal Disease)

Most of the research on SRMD in canines has been performed on racing Alaskan sled dogs. Studies have shown that 48% of these dogs develop gastric erosions or ulcers after completion of the Iditarod sled dog race over the course of 1,100 miles. Omeprazole (0.85mg/kg PO SID) was significantly superior to high-dose famotidine (1.7mg/kg BID) in reducing SRMD. SRMD has been also documented in Labrador retrievers undergoing explosive detection training. While there is compelling evidence to support preventive use of gastroprotective medications in performance animals, such evidence is lacking in critically ill dogs and cats. In human ICU patients there are safety concerns about administering acid suppressants to prevent SRMD due to an increased risk of ventilator associated pneumonia and C. difficile-associated diarrhea.

Renal disease

Gastric mineralization, gastric gland atrophy, and hypergastrinemia are typically documented in dogs and cats with advanced renal disease; however, ulcerative or erosive lesions are uncommon. A recent study did not reveal any significant differences in serum gastrin and gastric pH between healthy cats and cats with CKD, suggesting that cats with renal disease may not need gastric acid suppression. Moreover, prolonged therapy with acid suppressants in people can cause calcium and PTH derangements, osteoporosis, and pathologic fractures.

Positive fecal occult blood tests have been documented in dogs with CKD. The panel of experts recommends acid suppression in dogs and cats with renal disease that have additional risk factors for ulceration, or when concern for severe GI bleeding (melena, iron deficiency anemia) or vomiting-induced esophagitis exists.

Pancreatitis

Gastric acid suppressants are frequently used in acute pancreatitis in dogs and cats, despite the lack of evidence supporting their use. A recent placebo-controlled study failed to demonstrate a benefit to pantoprazole administration in human patients with acute pancreatitis.

Reflux esophagitis

Gastroesophageal reflux during anesthesia is associated with 46-65% of cases of benign esophageal strictures in dogs. Pre-anesthetic administration of IV esomeprazole at 12-18 hours and 1-1.5 hours prior to anesthetic induction to 22 dogs was associated with a significant increase in gastric and esophageal pH throughout the surgery. Similarly, administration of PO omeprazole to cats 18-24 hours and 4 hours prior to anesthesia resulted in comparable results.

ITP

GI bleeding is affected by the surrounding pH. Experimental studies in animals show that platelet aggregation at an ulcer is essentially normal at a gastric pH of 7.4, but progressively diminishes as the pH drops, until it is absent at a pH ≤6.2. GI hemorrhage is rarely observed in people with ITP but is common in dogs; therefore, acid suppressants are commonly used as adjunctive drugs in these patients.

FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

New drugs are being investigated to overcome the limitations of first-generation PPIs such as omeprazole, including interpatient variability, interaction with other drugs, and the delayed onset of action. Dexlansoprazole MR has the longest proton pump inhibitory effect of all known PPIs, due to its extended release. This drug is highly efficacious, safe, can be administered without regard to meals, and has dual release in the duodenum and small intestine.

Potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs) such as vonoprazan also inhibit the proton pump, but do not require protection from acid or prior activation of proton pumps to achieve their effect. The judicious application of these innovative therapeutic agents should further optimize the management of acid-related disorders in veterinary medicine.