-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Maureen Carroll, DVM, DACVIM

By Maureen Carroll, DVM, DACVIM

617-541-5186

Cobalamin, or vitamin B12, is a water soluble vitamin that is an essential cofactor for many enzyme systems in humans and animals. Animals are unable to synthesize cobalamin and are dependent on nutritional sources. Deficiency in this very important vitamin is common, and only occurs where the patient is suffering from gastrointestinal (GI) malabsorption. Cobalamin is an essential cofactor for certain enzyme systems, nucleic acid synthesis, amino acid metabolism and hematopoiesis. Intrinsic factor is required for absorption of cobalamin in the ileum.

Cobalamin metabolism:

As cobalamin is only acquired from dietary intake, once ingested, it is bound to the transport protein haptocorrin, and is subsequently delivered to the small intestine for absorption.

Free cobalamin is released in the small intestine and bound to intrinsic factor (IF), a glycoprotein produced by the parietal cells of the stomach (humans/ dogs) and pancreas (dogs, and exclusively for cats). The Cobalamin- IF complex is absorbed by receptors in the ileum to mid-jejunum in dogs, and in cats (and humans) only in the ileum. This membrane-bound receptor is called the Cubam receptor, and is comprised of two protein subunits: one is the cubilin (CUBN) subunit and the other is the amnionless (AMN) subunit. Once bound to these receptor subunits, endocytosis ensues and cobalamin is absorbed into the cell.

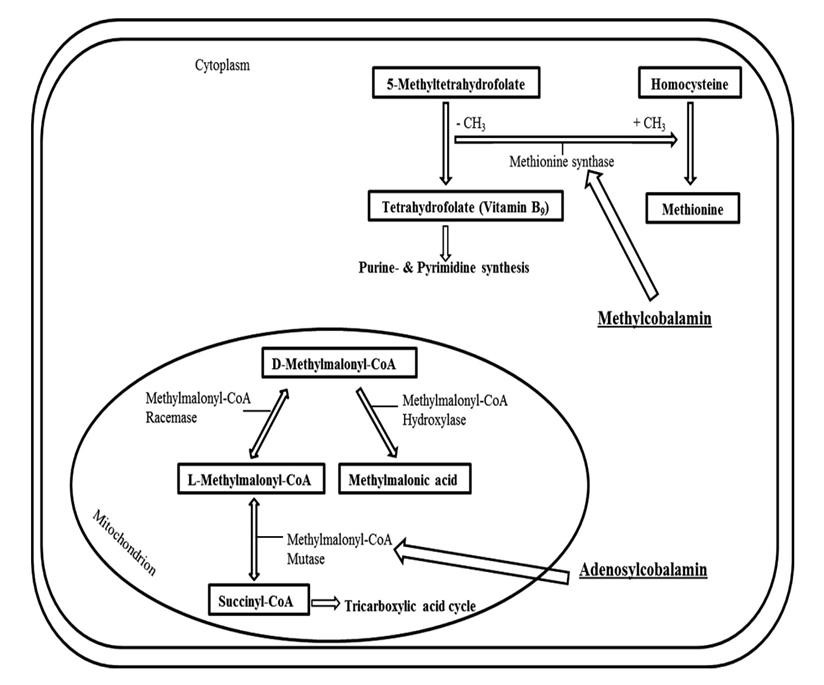

The two most important intracellular reactions involving cobalamin are depicted in the diagram below: One is the conversion of methylmalonyl- CoA à succinyl CoA, which occurs in the mitochondria. The second is the re-methylation of homocysteine to methionine, which occurs in the cytoplasm.

Defects in the Cubam receptor and its associated subunits, or defects in intracellular metabolism of cobalamin can also result in malabsorption and deficiency.

Conditions associated with Cobalamin deficiency

Genetic defects have been identified in many breeds of dogs including Beagles, Border Collies, Shar Pei’s, Giant Schnauzers and Australian Shepards. For example, the defect in Beagles and Border Collies: 2 independent mutations in the Cubilin gene. Congenitally affected Shar Peis suffer from a defect in intracellular metabolism of cobalamin. Giant Schnauzers have a defect in the AMN gene. In humans, Imerslund-Gräsbeck Syndrome (IGS) is a defect in either subunit gene-cubilin or AMN. Breed- related congenital defects in cobalamin metabolism have not been identified in cats.

Cobalamin deficiency is observed with several diseases, including: Inflammatory bowel disease, GI lymphoma, intestinal dysbiosis, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, short bowel syndrome, pancreatitis, as well as in cases of gastrinoma, as this can affect both gastric and pancreatic secretion of intrinsic factor.

Clinical signs of Cobalamin deficiency:

Cobalamin deficiency in humans can result in failure to thrive, pernicious anemia (normocytic/ nonregenerative), proteinuria and neurological damage (human infants). In dogs, congenital cobalamin deficiency can result in clinical abnormalities including failure to thrive, poor body condition, weight loss, inability to gain weight, cachexia, lethargy, weakness, anorexia, diarrhea, vomiting, dysphagia, oral ulcerations, hematopoietic abnormalities (nonregenerative anemia, neutropenia), and proteinura. Symptoms can occur as early as 6-12 weeks of age, with cases being identified clinically in patients up to 3-4 years of age.

In Border Collies there are case reports describing congenital liver dysfunction, which histologically responds to cobalamin supplementation once the deficiency is identified. Hyperhomocysteinemia (see diagram) can cause liver damage in mice by oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and activation of pro-inflammatory factors. In chronic inflammatory states stellate cells produce collagen, which is deposited as a delicate reticulin network in the space of Disse during chronic hepatic injury. This can result in inflammatory cell-infiltration and signs of hepatitis and potentially mild fibrosis.

Acquired forms of cobalamin deficiency usually present with gastrointestinal symptoms; blood dyscrasias are unusual. Neurological symptoms are occasionally reported (blindness in cats), but are unusual.

Diagnosis of Cobalamin deficiency:

There are multiple methods to diagnose cobalamin deficiency, from simply measuring a serum cobalamin level, to running serum homocysteine and methylmalonic acid (MMA) levels, as well as running MMA urine levels. In Shar Peis, due to the nature of the genetic defect, not only are these dogs deficient in cobalamin they may have 10x higher levels of serum methylmalonic acid than other cobalamin deficient dogs/breeds (once again refer to diagram/mitochondrial pathway). In cats, elevations in serum methylmalonic acid concentrations actually more accurately reflect cobalamin deficiency than measuring cobalamin itself. Therefore in cats that one might suspect a cobalamin deficiency, with a cobalamin measuring within reference range, running an MMA level might prove diagnostic for the deficiency. The incidence of cobalamin deficiency in cats with GI lymphoma is higher than in cats with inflammatory bowel disease.

Treatment

Treatment of cobalamin deficiency is very simple, and can be attempted as a sole therapy, or in conjunction with treatment for the underlying disease process. I have had certain canine patients respond to cobalamin supplementation alone, and resolve their underlying symptoms associated with enteropathy. It is also well established that hypocobalaminemic cats with IBD or GI lymphoma have superior responses to medical therapy for the disease process when cobalamin supplementation is a part of the treatment regime.

Subcutaneous and oral routes have been published, the route identified based on the pathology in the patient. For example, patients with short bowel syndrome, especially if the ileum is compromised, would require subcutaneous B12 injections as the area of absorption of B12 occurs mostly in at the Ileum. For other patients, a recent article was published examining oral B12 supplementation in dogs with chronic enteropathies, and found that normal levels can be achieved with this route of administration. Experience has shown that cats on oral cobalamin can achieve normal serum levels over time.

Dogs

Oral dosing: with a body weight of 1–10 kg received ¼ of a 1 mg tablet daily; 10–20 kg ½ of a 1 mg tablet daily, >20 kg received 1 tablet daily.

Subcutaneous dosing:

Subcutaneous dosing: 250- 1200 µg once weekly for 6 weeks then monthly based on follow up cobalamin levels

Cats:

Oral dosing: 1/8 to ¼ of a 1 mg tablet daily

250 µg subcutaneously once weekly for 6 weeks, then monthly based on follow up testing.

Summary:

Cobalamin deficiency in dogs and cats should be suspected and tested for in all patients with a history of enteropathy, pancreatic disease, and liver disease in cats. Young dogs, especially those of the breeds described above, should be tested for congenital cobalamin deficiency if unexplained symptoms of GI, hematologic, liver, kidney or failure to thrive are identified.

Genetic testing is available for the Border collies, Beagles, Australian Shepherds and Giant Schnauzers. Organizations that accept samples for testing include Paw Print Genetics, Genomia, PennGen and Laboklin.

Supplementation is very simple, and in most instances can result in normal serum levels over time.

For more information, please contact Angell’s Internal Medicine Service at 617-541-5186 or internalmedicine@angell.org.

REFERENCES:

- J Vet Intern Med 2014;28:666–671 Degenerative Liver Disease in Young Beagles with Hereditary

Cobalamin Malabsorption Because of a Mutation in the Cubilin

Gene P.H. Kook, M. Drogem € uller, T. Leeb, J. Howard, and M. Ruetten - J Vet Intern Med 2014;28:356–362 Selective Intestinal Cobalamin Malabsorption with Proteinuria

(Imerslund-Gr€ asbeck Syndrome) in Juvenile Beagles J.C. Fyfe, S.L. Hemker, P.J. Venta, B. Stebbing, and U. Giger - The Veterinary Journal 197 (2013) 420–426 Serum homocysteine and methylmalonic acid concentrations in Chinese Shar-Pei dogs with cobalamin deficiency Niels Grützner a,, Romy M. Heilmann a, Kenneth C. Stupka a, Venkat R. Rangachari a, Katja Weber a,

Andreas Holzenburg b,c, Jan S. Suchodolski a, Jörg M. Steiner a

4.Vet Clin Pathol. March 2013;42(1):61-5.

Evaluation of the MYC_CANFA gene in Chinese Shar Peis with cobalamin deficiency.

Niels Grützner 1, Micah A Bishop, Jan S Suchodolski, Jörg M Steiner

- Vet Intern Med 2013;27:1056–1063 The Relationship of Serum Cobalamin to Methylmalonic Acid

Concentrations and Clinical Variables in Cats

P. Worhunsky, O. Toulza, M. Rishniw, N. Berghoff, C.G. Ruaux, J.M. Steiner, and K.W. Simpson - 25th ECVIM-CA Congress, 2015

Oral Cobalamin Supplementation in Cats with Hypocobalaminemia

- Toresson1; J.M. Steiner2; J. Suchodolski2; M. Göransson1; L. Elmgren1; T. Spillmann3

- J Vet Intern Med. 2016 Jan-Feb;30(1):101-7.

Oral Cobalamin Supplementation in Dogs with Chronic Enteropathies and Hypocobalaminemia.

Language: English

L Toresson 1, J M Steiner 2, J S Suchodolski 2, T Spillmann 1