-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Patty Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (anatomic and clinical pathology)

By Patty Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (anatomic and clinical pathology)

angell.org/lab

617-541-5014

Introduction

Lymph node fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology is a convenient, rapid, relatively inexpensive and high-yield diagnostic procedure in dogs. Highly cellular aspirates are readily obtained in most cases. FNA of peripheral lymph nodes is performed for the following purposes: 1) diagnosis of inflammation, infectious disease, reactive hyperplasia, lymphoma, or metastatic neoplasia; 2) staging and monitoring relapse or treatment response in known malignancy such as lymphoma; and 3) obtaining samples for clonality, immunophenotyping or immunocytochemistry evaluations. This article will review common cytologic findings for canine peripheral lymph nodes that are easy to access by general practitioners without imaging modalities.

Normal Lymph Node

A normal lymph node is small and may be challenging to locate and/or aspirate. FNA may obtain only lipid and adipocytes if the lymph node is small. When adequately cellular samples are obtained from a normal lymph node, small, well-differentiated lymphocytes will account for at least 85% of the total nucleated cell population (see Figure 1). The remaining lymphoid cells (intermediate to large size) will account for <10% to 15% of the population.1 Low numbers of plasma cells and macrophages are commonly found. Infrequent neutrophils, eosinophils and mast cells may also be present in a normal lymph node.

Reactive or Hyperplastic Lymph Node

A reactive or hyperplastic lymph node develops when antigens in sufficiently high concentration reach the draining lymph node and stimulate the immune system. No definitive separation between a normal and reactive lymph node is evident based on cytology alone. An enlarged lymph node is generally considered to be “reactive” even if the cellular composition is similar to that of a normal lymph node. However, in most instances, the proportion of intermediate to large lymphoid cells will be increased to greater than 15% and plasma cells will be increased to greater than 5% of the nucleated cell population in some areas of the smear2 (see Figures 1 and 2). Plasma cells will occasionally contain Russell bodies (see Figure 2) which are immunoglobulin packets (referred to as Mott cells). Immature plasma cells or lymphocytes transforming to plasma cells may be observed. Macrophages may represent greater than 2% of the nucleated cell population (see Figure 1).

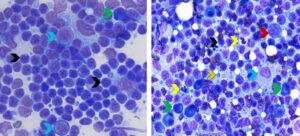

Figure 1. Aspirates from a normal popliteal lymph node (left) and reactive prescapular lymph node (right). Left. Greater than 85% of lymphoid cells are small lymphocytes (black arrows) and less than 5% are large lymphoid cells/lymphoblasts (red arrows). The green arrow identifies a plasma cell which can be present in low numbers in normal lymph nodes (Wright-Giemsa, 750x magnification) Right. The hyperplastic/reactive lymph node has a mixed lymphoid population with predominance of small lymphocytes (black arrow), fewer large lymphoid cells/lymphoblasts (red arrow), moderately increased numbers of plasma cells (green arrows), and mildly increased neutrophils (yellow arrows) and macrophages (blue arrow). The orange arrow with blue outline identifies a lymphoglandular body, which is a fragment of cytoplasm from a ruptured lymphocyte. They can be found in both reactive lymph nodes and lymph nodes with lymphoma. (Diff-Quik, 600x magnification)

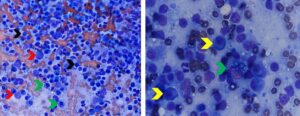

Figure 2. Aspirates of reactive peripheral lymph nodes. Left. Note mixed lymphoid population with predominance of small lymphocytes (black arrows), fewer large lymphoid cells/lymphoblasts (red arrows), moderately increased numbers of plasma cells and Mott cells (green arrows). (Diff-Quik, 500x magnification) Right. Higher magnification view of another hyperplastic/reactive lymph node showing the appearance of a Mott cell (plasma cell with Russell bodies/immunoglobulin packets) compared to a plasma cells without Russell bodies (yellow arrows). (Diff-Quik, 1000x magnification)

Lymphadenitis

Inflammation of the lymph node, known as lymphadenitis, may be primary or secondary (lymph node draining a site of inflammation). Inflammatory cells may include neutrophils, eosinophils, macrophages or a combination of these cell types. If macrophages are epithelioid or multinucleated giant type, the inflammation is designated as granulomatous.1 Table 1 outlines differential diagnoses that should be considered with specific types of inflammation in the lymph node. A diligent search for bacterial, fungal and protozoal organisms is warranted when lymphadenitis is identified (see Figure 3). Additional testing for infectious disease which may include culture, PCR and/or serology.

Table 1. Differentials for Lymphadenitis by Cell Type

|

Predominant |

Differential |

| Neutrophilic | Bacterial Immune-mediated disease Inflammation associated with neoplasia, vasculitis, cutaneous ulceration, trauma or tissue necrosis |

| Eosinophilic | Allergic/hypersensitivity disorders Hypereosinophilic syndrome Paraneoplastic syndrome (lymphoma, mast cell tumor and carcinoma) |

| Granulomatous/ Pyogranulomatous |

Immune-mediated disease Foreign body reaction Mycobacteriosis Protozoal (Leishmaniasis, Toxoplasmosis) Salmon poisoning disease (Neorickettsia helminthoeca) Pythiosis Protothecosis Fungal (Blastomycosis, Histoplasmosis, Cryptococcosis, Coccidioidomycosis) |

Figure 3. Aspirates of lymph nodes with lymphadenitis and infectious agents (blastomycosis-left; leishmaniasis-right). Left. Note relatively few lymphocytes (black arrows) and high numbers of neutrophils blue arrows) and macrophages (green arrows). The yellow arrows identify Blastomyces dermatitidis yeast. Note the yeast are approximately 10-20 micron, dark blue in color with a thick wall and thin, non-staining capsule. (Diff-Quik, 500x magnification) Right. Note mixed lymphoid population and numerous small purple “parachute”-shaped Leishmania spp. amastigotes present within the cytoplasm of a macrophage and free within the background (yellow arrows). (Diff-Quik, 1000x magnification)

Lymphoma

Cytologic evaluation of lymph node aspirates is usually sufficient for diagnosing the majority of canine lymphomas. Aspiration of popliteal and prescapular lymph nodes is preferred over mandibular lymph nodes when generalized lymphadenopathy is present because mandibular lymph nodes are frequently enlarged and reactive due to constant exposure to antigens.2 A diagnosis of lymphoma can often reliably be made when greater than 50% of the lymphoid population is composed of immature lymphoid cells (see Figure 4). Greater certainty of a lymphoma diagnosis is made when 80% or more of the lymphoid cells are immature lymphoid cells.1 A diagnosis of lymphoma is easiest to make when the immature cells are medium and large in size (1.5 to 3 times or more the size of RBCs) with finely granular (dispersed) chromatin and visible nucleoli. Mitotic figures may be more numerous than seen in reactive lymph nodes, but this finding alone is not a reliable indicator of malignancy. This morphologic type of high-grade lymphoma consisting of immature medium to large lymphoid cells accounts for the majority of lymphomas in dogs, but up to 20% are small cell lymphomas.1 Lymph nodes with small cell or indolent lymphoma or those with an early lymphoma cell infiltrate (<50% of lymphoid cells are immature) are more challenging to diagnosis cytologically and often require additional diagnostic evaluations (flow cytometry, PCR for assessment of clonality, or histopathology and immunophenotyping). A retrospective study of indolent lymphomas reported that a distinctive form of a small cell subtype of T-cell lymphoma, designated T-zone lymphoma, comprises up to 61.7% of canine indolent small cell lymphomas. T-zone lymphoma is most commonly observed in Golden Retrievers and Maltese dog breeds but can occur in many others as well as mixed breeds.3 Consider submission to a pathologist for confirmation.

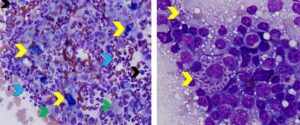

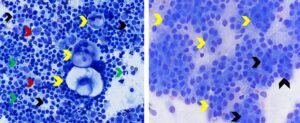

Figure 4. Aspirates from lymph nodes with high grade B cell lymphoma (left) and low grade (T-zone) lymphoma (right). Left. Greater than 80% of cells are atypical medium to large lymphoid cells with dispersed chromatin and multiple prominent nucleoli (red arrows). Note size of large lymphoid cells relative to small lymphocytes (black arrows) and neutrophils (yellow arrow). The green arrow identifies a mitotic figure. Immunophenotyping confirmed B cell origin. (Diff-Quik, 600x magnification) Right. Note that >85% of cells are morphologically distinct small-sized lymphocytes with round nuclei, loosely clumped chromatin and increased amounts of pale blue cytoplasm which often extends from one pole of the cell in a hand mirror configuration (yellow arrows). Immunophenotyping by flow cytometry confirmed T-zone lymphoma. (Diff-Quik, 500x magnification)

Metastatic Neoplasia

Metastatic neoplasia is suspected when cell types not normally present in lymph nodes or excessive numbers of cell types normally present (such as mast cells) are identified in lymph node aspirates. Neoplastic cells are usually obtained if metastasis has progressed to cause clinically enlarged lymph nodes; however, small foci in normal-sized lymph nodes may be missed on aspiration.1 The sensitivity of detecting low numbers of metastatic cells may be increased by using molecular techniques to detect the presence of tumor antigen mRNA.4 The most common types of metastatic neoplasia observed in canine lymph nodes at Angell Animal Medical Center include mast cell neoplasia, carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.

Distinguishing between a benign mast cell population and mast cell tumor neoplasia can be challenging in some cases. One study found that mast cell tumor metastasis is most commonly observed in patients with lymph node enlargement, mast cell clustering (3 or more aggregating mast cells) or the presence of mast cells with atypical morphology (see Figure 5).5 More than 3% mast cells should also raise suspicion of mast cell tumor metastasis.

One study found that detection of metastatic melanoma to regional lymph nodes via FNA can be highly sensitive (92%) but was influenced by several factors including use of immunostains, lymph node location and lesion location.6 Metastatic melanoma cells may be poorly or sparsely pigmented (see Figure 5) making confirmation of melanocytic origin challenging. Additionally, pigment in melanocytes should not be confused with that in melanophages that have phagocytized melanin pigment originating from lesions drained by the lymph node. Neoplastic melanocytes usually have less cytoplasmic volume and less vacuolated cytoplasm than melanophages. Hemosiderin, bile, carbon and other pigments in macrophages may be confused with melanin.1 Immunocytochemistry using a marker such as Melan-A may be helpful in confirming a diagnosis of metastatic amelanotic melanoma.2

Carcinomas frequently metastasize to lymph nodes. Metastatic epithelial cells may occur singly or in cohesive aggregates (see Figure 6). They are frequently large polygonal cells that bear no resemblance to cellular components of reactive or hyperplastic lymph nodes, thus are relatively easy to identify.1

Spindle-cell sarcomas metastasize to lymph nodes less commonly than carcinomas and mast cell tumors. They are the most difficult to recognize because of their individualized cell presentation and overlap in appearance with reparative fibroblasts that may be present in lymph nodes.2 The finding of anaplastic spindle cells exhibiting marked morphologic atypia can support a diagnosis of metastatic spindle-cell sarcoma.

Figure 5. Aspirates of lymph nodes with metastatic amelanotic melanoma (left) and mast cell neoplasia (right). Left. Note paucity of lymphocytes (black arrow) and numerous neoplastic large round or pyriform-shaped cells that have large round to oval nuclei with stippled chromatin and multiple irregular nucleoli of variable size (red arrows). A low proportion of neoplastic cells have fine dark green pigment (melanin) in their cytoplasm (yellow arrows). (Diff-Quik, 750x magnification) Right. Note numerous sparsely granulated mast cells (yellow arrows) exhibiting marked morphologic atypia (large round nucleus, one or multiple large round to irregular nucleoli, moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis) among mixed lymphoid cells (black arrows). The green arrow identifies a plasma cell and the red arrows identify eosinophils. (Diff-Quik, 750x magnification)

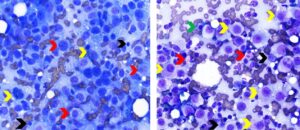

Figure 6. Metastatic squamous cell in mandibular lymph node (left) and metastatic anal sac adenocarcinoma in inguinal lymph node (right). Left. Note singly occurring very large polygonal epithelial cells (yellow arrows) exhibiting morphologic atypia (one or two oval nuclei with multiple irregular nucleoli, moderate anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, and large vacuoles in cytoplasm) among numerous mixed lymphoid cells. Black arrows identify small lymphocytes. Red arrows identify large lymphoid cells/lymphoblasts. Green arrows identify neutrophils. (Diff-Quik, 500x magnification) Right. Note absence of lymphoid cells which may occur when neoplastic cells replace lymph node parenchyma. Yellow arrows identify cohesive aggregates of polygonal to round epithelial cells. Some of the neoplastic epithelial cells are forming acini (black arrows) (Wright-Giemsa, 750x magnification)

Summary

Cytologic evaluation of canine peripheral lymph nodes is frequently rewarding due to the ease of sample collection, affordability, and high diagnostic yield. With practice and experience, cytologic differentiation of lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphoma, lymphadenitis and metastatic neoplasia is achievable in many cases.

References

- Valenciano, A and Cowell R: Cowell and Tyler’s Diagnostic Cytology and Hematology of the Dog and Cat, 5th edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2020, p. 171-181.

- Raskin R and Meyer D: Canine and Feline Cytology—A Color Atlas and Interpretation Guide, 2nd edition. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier, 2010, p. 77-104.

- Seelig D, Webb T, Avery P, Avery A. Canine T-zone lymphoma: unique immunophenotypic features, outcome and population characteristics. JVIM. March, 2014;28(3).

- Zavodovskaya R, Chein MB, London CA. Use of kit internal tandem duplications to establish mast cell tumor clonality in 2 dogs. JVIM 2004:18(6):915-917.

- Kirk EL, et al. Cytological lymph node evaluation in dogs with mast cell tumors: association with grade and survival. Vet Comp Oncol. 2009;7(2):130-138.

- Doubrovsky A. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fine needle biopsy for metastatic melanoma and its implication for patient management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(1):323-332.