-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Ruth Van Hatten, DVM, DACVR

By Ruth Van Hatten, DVM, DACVR

angell.org/diagnosticimaging

617-541-5139

Thoracic radiography is one of the most widely available diagnostic tools when evaluating cardiovascular structures; however, radiographs are only a piece of a larger puzzle. It is important to understand the limitations of thoracic radiographs when assessing the heart and pulmonary blood vessels, as a normal cardiac silhouette on radiographs does not rule out underlying cardiac disease. The wide variety of shapes and sizes in our patients, as well as positioning and technique, results in differing appearances of the heart and thoracic cavity on radiographs that can make interpretation challenging. Being able to differentiate between normal and abnormal can be the hardest first step when evaluating thoracic radiographs.

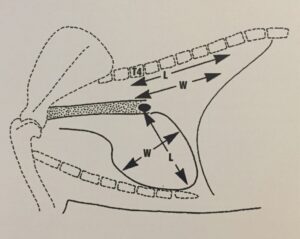

Figure 1: Vertebral heart score. The length (from the carina to the apex) and width (at the widest point) of the heart is compared against the length of the T4 vertebral body. (Image obtained from BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Thoracic Imaging)

There are many different “rules” in place for determining normal cardiac silhouette size on radiographs demonstrating that using an objective measurement alone can result in large overlap between normal and abnormal. For example, mild cardiomegaly and mild pericardial effusion are often considered within normal limits on radiographs, and thus subtle changes can be missed. One commonly used rule is comparing the max diameter of the heart on lateral radiographs to the number of intercostal spaces (in dogs, the normal heart size is usually within 2.5 to 3.5 intercostal spaces and in cats, 2 to 3 intercostal spaces). On the VD/DV view, an additional rule is the cardiac silhouette should not fill more than 2/3rds of the thoracic cavity (pleura to pleura). Another method of measuring heart size on radiographs is the vertebral heart score (Figure 1). This method is fraught with errors as there is large variation between different breeds and many publications to demonstrate this fact. With experience, the vertebral heart score has not been proven to be better than subjective measurement of heart size on radiographs. However, this method of measurement is extremely useful when comparing heart size in the same patient over time on serial radiographs.

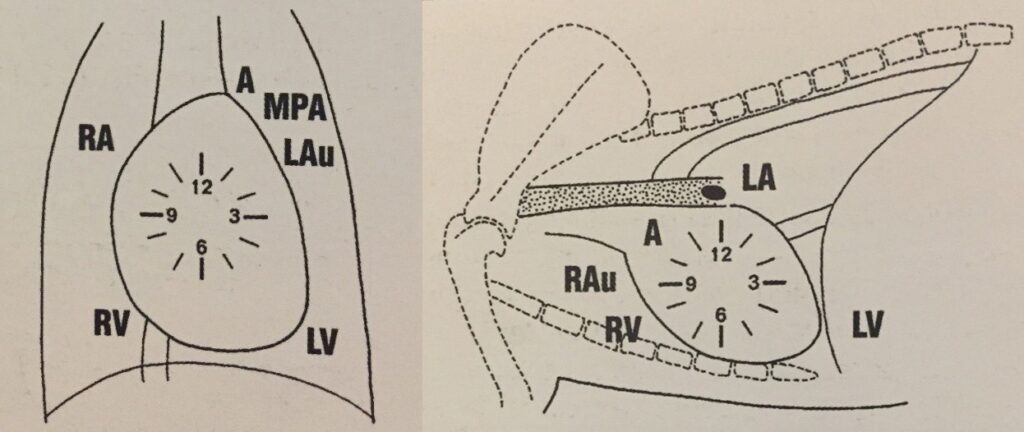

The clock face analogy (Figure 2) is a valuable tool when determining which part of the heart is enlarged when there is a focal bulge along the cardiac silhouette. Most commonly, the left atrium will be enlarged and associated with mitral valve disease (12-1 o’clock on lateral and 5-7 o’clock on VD/DV). Right-sided heart disease can be associated with both acquired (e.g. pulmonary hypertension, heart worm disease) and congenital (e.g. tricuspid dysplasia) diseases, and seen as a “reverse D” shape on the VD/DV view. On the lateral view, drawing a line from the carina to the apex can also assess right-sided cardiomegaly; normally, 2/3rd of the heart is located cranial to the line and 1/3rd caudally. If more of the heart lies cranial to this line (e.g. 4/5th cranial and 1/5th caudal), this can indicate right-sided heart enlargement. The aorta and main pulmonary artery can also become focally enlarged (12-1 o’clock and 1-2 o’clock, respectively on the VD/DV view) and depending on the age and breed will help differentiate between various congenital heart defects (e.g. aortic and pulmonic stenosis, respectively) and acquired diseases (e.g. systemic hypertension and pulmonary hypertension, respectively). The clock face analogy can also fail us at times as mild obliquity on the VD/DV view can falsely create bulges in the cardiac silhouette, and on the lateral view, the aorta, main pulmonary trunk and heart base tumors are all located in the same region making it difficult to differentiate.

Figure 2: Clock-face analogy. A, Aorta; MPA, Main Pulmonary Artery; LAu, Left Auricle; LA, Left Atrium; LV, Left Ventricle; RAu, Right Auricle; RA, Right Atrium, RV, Right Ventricle. (Images obtained from BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Thoracic Imaging)

Thoracic radiographs are a mainstay for assessing cardiovascular structures; however, because fluid and soft tissue are the same opacity on radiographs, echocardiography is required for measuring heart chamber size and cardiac function. Radiographs give a global view of the overall heart size and shape, as well as pulmonary blood vessels, and are used to evaluate for cardiogenic pulmonary edema or underlying lower airway disease that may affect the heart (i.e. secondary pulmonary hypertension). Thus, when heart disease is suspected, both thoracic radiographs and a cardiology consultation with echocardiography are recommended and the two are considered complimentary.

Reference: Schwarz, T. and Johnson, V., eds. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Thoracic Imaging. Gloucester, UK: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, Woodrow House; 2008.