-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Referrals

- Referral Forms/Contact

- Direct Connect

- Referring Veterinarian Portal

- Clinical Articles

- Partners in Care Newsletter

CE, Internships & Alumni Info

CE Seminar Schedule

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Patty J. Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (Anatomic and Clinical Pathology)

Patty J. Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (Anatomic and Clinical Pathology)

Angell Animal Medical Center

angell.org/lab

pathology@angell.org

617 541-5014

Introduction

Cytologic evaluation of gastrointestinal (GI) neoplasia has become more commonly utilized given the widespread use of abdominal ultrasound (AUS) in both general and specialty veterinary practices. AUS allows for identification of solitary or multiple masses or thickening of the gastrointestinal tract, which in many cases can be sampled via fine-needle aspiration (FNA) for cytologic evaluation. While other methods of sample collection such as endoscopic brush and impression smears of surgical or endoscopic biopsy samples may be suitable for cytologic diagnosis, these methods are more expensive and/or invasive to obtain than FNA. In this article, the following topics will be covered: 1) the diagnostic value of FNA for cytologic diagnosis of GI tumors, and 2) cytologic features of common types of canine GI tumors sampled via ultrasound-guided FNA.

Diagnostic Value of Ultrasound-Guided FNA for Cytologic Diagnosis of GI Tumors

Table 1 lists the advantages and disadvantages of ultrasound-guided FNA for diagnosis of GI tumors.

Ultrasound-guided aspirates are less invasive and less expensive to obtain than endoscopic and full-thickness biopsies for histopathology. Nevertheless, histopathology remains the gold standard and may be required for definitive diagnosis of certain types of neoplasms. In a retrospective study which evaluated the diagnostic value of cytologic examination of GI tumors in dogs and cats, there was partial or complete agreement between cytologic and histologic diagnosis for 48 of 67 (71%) fine needle aspirates.1 This degree of agreement warrants use of FNA for obtaining a preliminary diagnosis, especially when owner financial concerns or unstable patient condition makes surgically obtaining a biopsy sample less desirable. Cytologic evaluation may also be helpful for surgical planning.

Although ultrasound-guided FNA is less invasive and does not carry the risk associated with general anesthesia required for endoscopy and surgery, the procedure is not completely without risk. Local hemorrhage and leakage of intestinal content are possible complications associated with needle penetration of the GI tract. Hemorrhage is an uncommon complication and the risk can be minimized by assessing the patient’s coagulation status (platelet count, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time–PT/PTT) prior to FNA. FNA should be avoided in patients with platelet counts <50,000/µl and patients that have significantly elevated PT or PTT values. Intestinal content leakage is a life-threatening complication, but can be avoided with careful selection of the needle insertion site.2 Dislodging neoplastic cells from a tumor with release into circulation or tissue fluid during FNA is a possibility because the cells lack cohesiveness and can migrate and colonize. This risk can be minimized by using a needle of 22 gauge or less and by avoiding multiple needle insertions into the mass.3

Table 1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Ultrasound-Guided FNA for Cytologic Diagnosis of GI Tumors

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Rapid diagnosis | May not yield a definitive diagnosis in some cases |

| Relatively inexpensive | Location of mass may not be accessible or degree of GI thickening not sufficient for aspiration |

| Less invasive than endoscopically or surgically obtained biopsies | Risk of intestinal content leakage or local hemorrhage with needle penetration |

| General anesthesia not required | Risk of tumor cell seeding |

Cytologic Features of Canine GI Tumors

The most commonly reported tumors of the canine gastrointestinal tract can be divided into three general categories: epithelial, spindle cell (mesenchymal) and round cell. Table 2 shows the types of GI tumors that are common in each category.1,4 With sufficient cellularity in a good quality FNA, cytologic evaluation may allow for determination of the general category of a tumor. Table 3 shows cytologic features of four types of GI tumors that we have observed at our institution.

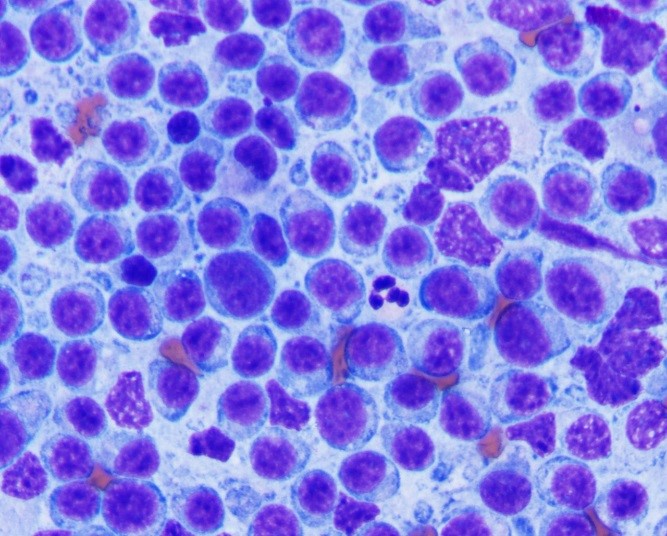

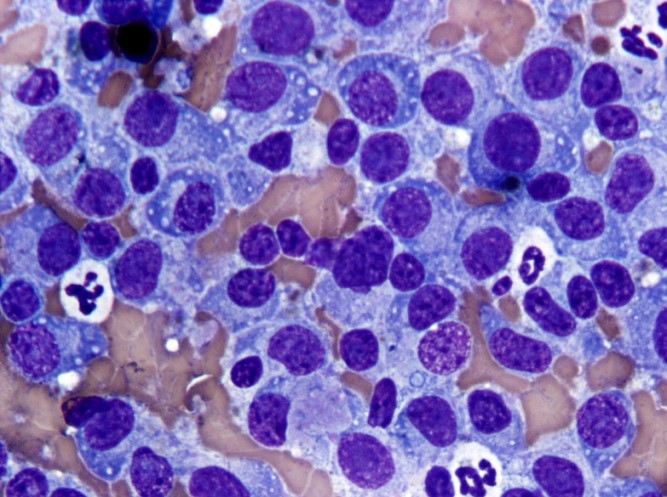

Round cell tumors can often be more specifically categorized as to the cell of origin (lymphoma, plasmacytoma or mast cell tumor). Plasmacytoma may be challenging to differentiate from plasmacytic inflammation if the degree of cytologic atypia exhibited by the plasma cells is minimal. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry can be useful in achieving a definitive diagnosis. Lymphoma can be challenging to differentiate from hyperplastic mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue in some cases. When greater than 50% of the lymphoid population is composed of medium to large lymphoid cells with dispersed chromatin +/- visible nucleoli, lymphoma is the likely diagnosis. The cytology slides can be submitted for PCR for antigen receptor rearrangement, which differentiates reactive or hyperplastic versus neoplastic populations of lymphocytes. While small cell lymphoma of the GI tract can be challenging to differentiate from lymphocytic inflammation, this type of lymphoma occurs very infrequently in the canine GI tract unlike that of the feline GI tract.

Spindle cell tumors generally cannot be further categorized cytologically and require histopathology and immunohistochemistry for accurate determination of histogenesis. In addition, histologic evaluation may be required to definitively differentiate a reparative or reactive processes such as fibrosis or desmoplasia from a sarcoma. In a retrospective study, sensitivity of cytologic examinations of FNA was higher for animals with GI lymphoma (71%) than for animals with spindle cell tumors (44%).1 This difference is likely related to the intrinsic tendency of round cell tumors to exfoliate cells more readily compared to spindle cell tumors.

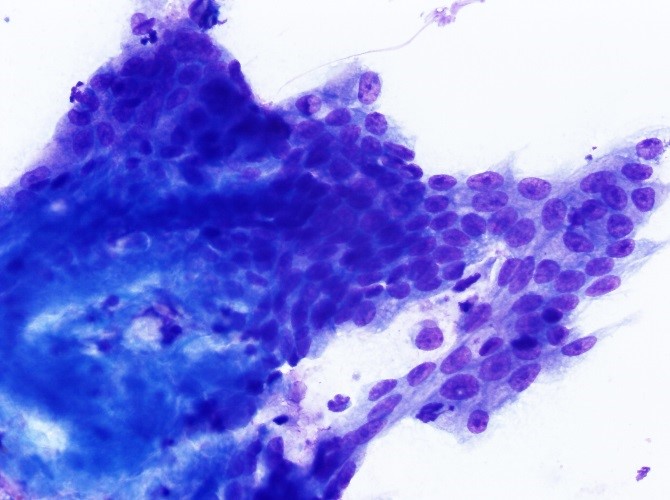

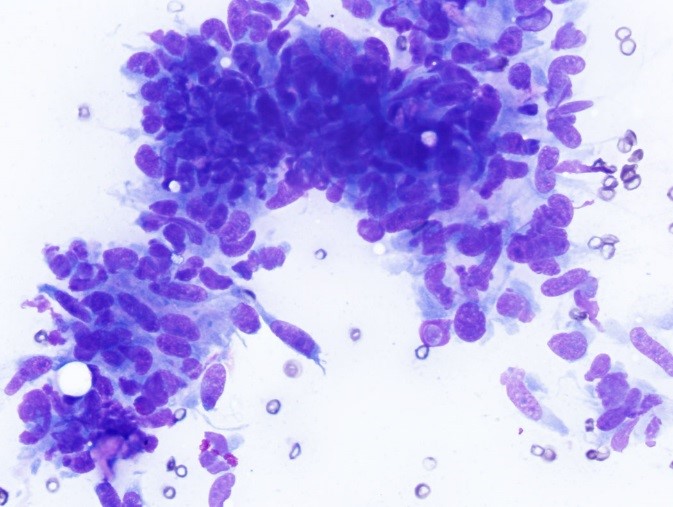

Epithelial neoplasms can be challenging to differentiate from normal or hyperplastic epithelium of the GI tract via cytologic evaluation. However, if sufficient criteria of malignancy are displayed by the epithelial cells, a presumptive diagnosis of carcinoma can be made. In the author’s experience, GI carcinomas with extensive desmoplasia (reactive, scirrhous connective tissue response) may not yield sufficient cells via FNA for cytologic diagnosis. Although gastrointestinal adenomatous hyperplasia is one of the most common GI mass diagnoses made via histopathology at our institution, sufficient numbers of epithelial cells are usually not obtained via FNA for cytologic diagnosis of this entity. Additionally, differentiation of adenomatous hyperplasia exhibiting epithelial dysplasia (cytologic atypia that is a non-neoplastic change) and gastrointestinal carcinoma via cytologic evaluation can be very challenging and often requires histopathology for definitive diagnosis.

It is not uncommon for GI neoplasms to be accompanied by inflammation, which may be observed cytologically. Inflammation can be associated with dysplasia in epithelial cell populations. For this reason, cytologic diagnosis of carcinoma when significant inflammation is present should be made with caution. Because neoplasms that involve the GI tract may cause ulceration of the mucosa, secondary bacterial infections may also be observed. Finding phagocytized bacteria is helpful in alerting the clinician to the presence of a second disease process that may require treatment. In the author’s experience, the presence of bacterial infection may increase the risk of gastrointestinal perforation.

Table 2. Canine GI Tumor Categories

| Epithelial | Spindle Cell (Mesenchymal) | Round Cell |

| Adenoma/ Adenomatous hyperplasia | Leiomyoma/Leiomyosarcoma | Lymphoma |

| Adenocarcinoma | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) | Extramedullary plasmacytoma (aka plasma cell tumor) |

| Carcinoma | Fibrosarcoma | Mast cell tumor |

Table 3: Cytologic Features of Four Types of Canine GI Tumors

aDiagnosis confirmed via histopathology and/or immunohistochemistry

bGIST-Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

cIHC – immunohistochemistry

dPCR for antigen receptor rearrangement (differentiation of reactive and neoplastic populations of lymphocytes)

eFlow cytometry +/- PCR may be useful in differentiating T cell versus B cell lymphoma

Summary

Cytologic evaluation of GI masses sampled via ultrasound-guided FNA may be useful in obtaining a presumptive or definitive diagnosis of neoplasia. This method is less expensive and less invasive than obtaining samples surgically, but does not always obtain sufficient numbers of cells for diagnosis. The risk of hemorrhage and intestinal content leakage can be minimized if appropriate precautions are taken. At our institution, cytologic evaluation has been useful in obtaining presumptive or definitive diagnosis of the following types of GI neoplasia if sufficiently cellular samples are obtained: lymphoma, plasma cell tumor, spindle cell tumors and carcinoma.

For more information on canine GI neoplasia, read “Canine GI Neoplasia” by Angell’s Pamela Mouser, DVM, MS, DACVP

References

- Bonfanti U et al. Diagnostic value of cytologic examination of gastrointestinal tract tumors in dogs and cats: 83 cases (2001-2004). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006 Oct 1;229(7):1130-3.

- Penninck D and d’Anjou M. Altlas of Small Animal Ultrasonography, 2nd Publisher: John Wiley and Sons, 2015, p. 306.

- Shymalak K et al. Risk of tumor cell seeding through biopsy and aspiration cytology. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2014 Jan-Apr 4(1):5-11.

- Haddad J. et al. Chapter 18: The Gastrointestinal Tract, in Cowell and Tyler’s Diagnostic Cytology and Hematology of the Dog and Cat, 4th edition, edited by Valenciano A. and Cowell R., Publisher: Elsevier, pp.