-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Pamela Mouser, DVM, MS, DACVP

Pamela Mouser, DVM, MS, DACVP

Anatomic Pathologist, Angell Animal Medical Center

pmouser@angell.org

www.angell.org/lab

617-541-5014

Introduction

The most enjoyable cases from a diagnostic pathologist’s perspective are those that have beautiful, picturesque lesions. I am often partial towards nice gross lesions, and gastrointestinal neoplasia can certainly provide some great photo opportunities. In this article, I will summarize just over 6 years of surgical biopsy data for canine gastrointestinal neoplasia (mid-2009 through late 2015), including samples taken from the stomach to the rectum; illustrate the gross appearance of common neoplastic lesions; and compare findings to published data.

Angell data summary

Of the 108 canine gastrointestinal (GI) neoplasms in our database from the past 6 years, the most common diagnoses in descending order were adenoma or adenomatous hyperplasia (32; 26 of which were rectal papillary adenoma submissions), adenocarcinoma (21), and lymphoma (13). If all sarcomas were considered together as a group, they weighed in at a total of 24 cases.

Angell submissions were further tabulated by section of the GI tract affected, and it is interesting to note that some tumor types predominated in certain areas (see Table 1). For example, eight of the 13 gastric neoplasms were epithelial proliferations ranging from adenomatous hyperplasia to gastric adenocarcinoma. Interestingly, there were no lymphoma diagnoses in the stomach, although this may represent case bias since a cytologic diagnosis of lymphoma may preclude surgical biopsy. One third of the neoplastic processes in the small intestine were diagnosed as carcinoma, and a second third as lymphoma. This is in contrast to the ileocecocolic junction, cecum, and colon, where adenocarcinoma and lymphoma were only diagnosed once each out of 17 neoplastic submissions. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) appeared to favor the cecum, although some of the unclassified sarcomas occurring at other sites may have been re-categorized as GISTs if immunohistochemical phenotyping had been performed. Over half of the rectal masses were papillary adenomas, and three cases classified as carcinoma were noted to be arising from rectal papillary adenomas. Rectal plasma cell tumors (plasmacytomas) were the next most common rectal tumor type, and tended to have a high recurrence rate (five of seven tumors).

Table 1: Canine gastrointestinal neoplasia diagnosed via biopsy between mid-2009 and late-2015, separated by submission site.

| Stomach | Small intestine | Ileocecocolic junction | Cecum | Colon | Rectum | TOTAL | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3 | 11 | 1 | 6* | 21 | ||

| Lymphoma | 11 | 1 | 1 | 13 | |||

| Sarcoma† | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| GIST | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 10 | ||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Adenoma/polyp | 5 | 1 | 26 | 32 | |||

| Plasma cell tumor | 1 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Leiomyoma | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Mast cell tumor | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 1 (insulinoma) | 1 | 2 | ||||

| TOTAL | 13 | 33 | 1 | 10 | 6 | 45 | 108 |

*Three cases of rectal carcinoma were in situ carcinomas arising within rectal papillary adenomas.

†Masses classified as sarcomas included lesions without IHC for further distinction, KIT-negative sarcomas that did not have morphology typical of leiomyosarcoma, and one extraskeletal osteosarcoma invading the small intestine.

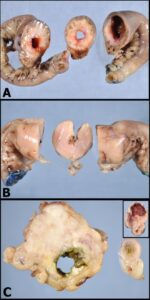

Figure 1: The gross photograph of an intestinal carcinoma in image A demonstrates a firm circumferential mass causing narrowing of the intestinal lumen. Close inspection of the cut section shows cystic spaces in the wall of the mass, representing either foci of necrosis or large cystic glands created by neoplastic epithelium. Image B: This smooth, homogenous tan mass causing full-thickness expansion and layer effacement of the intestinal wall is intestinal lymphoma. Note that the intestinal lumen is also narrowed with this mass. Image C: The irregular, eccentric intestinal mass with a fibrous appearance is a leiomyosarcoma. Compare this to the inset image of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Both lesions typically arise from the outer layers of the GI wall (tunica muscularis), which likely contributes to the eccentric distribution relative to the intestinal lumen.

Gross lesion appearance

The three major types of gastrointestinal malignancy are illustrated in figure 1, using small intestinal lesions as examples. Adenocarcinomas arise from the inner aspect of the GI wall (tunica mucosa), are often circumferential in the small and large intestine, and induce a desmoplastic response. These tumors are therefore firm, frequently cause stricture of the intestinal lumen, and may cause annular constriction of the wall referred to as a “napkin-ring” lesion. Lymphoma is also often circumferential, but tends to be more expansile than carcinoma causing effacement of all layers with a homogenous tan color. Intestinal sarcomas range from pale tan to almost white, are firm to fibrous, and have a more eccentric distribution compared to the other two lesions. Of course, regardless of how characteristic a mass appears grossly, histopathology is essential for final diagnosis!

Data comparison to published reports

In a recent review of alimentary neoplasia in dogs and cats,1 the author indicates that adenocarcinoma and lymphoma are the most common GI malignancies in dogs, which is corroborated with our data set if we do not lump all mesenchymal tumors together as “sarcomas”. The review article also suggests that carcinoma is the most common large intestinal malignancy in dogs, with the greatest proportion of carcinomas diagnosed in the rectum.1 If we group all of our neoplasms from the cecum to the rectum, our biopsy submissions show an equal number of carcinomas and GISTs, with several additional sarcomas that were not further characterized. I am uncertain whether the greater proportion of sarcomas in our data set represents a form a selection bias, reflects more frequent detection of small/incidental sarcomas through our consistent use of diagnostic imaging during case workups, or is simply a factor of our relatively low sample number.

Alimentary lymphoma in dogs is typically composed of large lymphoid cells, with T-cell phenotype most common.2 One retrospective study reported a remarkably short survival time (median survival of 13 days) in 30 dogs with gastrointestinal lymphoma which were treated with surgery, chemotherapy, both, or supportive care.3 A prospective study also reported a poor outcome in dogs treated with multiagent chemotherapy; just over 50% of dogs achieved remission and the overall median survival time was 77 days.4 Given this survival data, I suspect that surgery is avoided in these patients when possible. Thus, our biopsy data set may underestimate the incidence of GI lymphoma in dogs, as a cytological confirmation of this diagnosis likely precludes surgical biopsy.

Historically, the majority of GI mesenchymal tumors were diagnosed as leiomyosarcomas. However, recent advances in immunohistochemistry have prompted a more careful evaluation of sarcomatous intestinal masses, and suggest that a significant proportion (often well over 50%) of tumors previously classified as smooth muscle origin actually arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal. These cells—and their associated tumors—are positive for KIT (CD117) via immunohistochemistry, and are now classified as gastrointestinal stromal tumors.5,6 The distinction between intestinal sarcoma types may be more than just an academic endeavor, as there is evidence that GISTs metastasize more commonly than their smooth muscle counterparts.7 Positivity for KIT, a tyrosine kinase receptor, may also provide options for treatment with specific chemotherapeutic agents such as those now widely used for canine mast cell tumors.

Summary

The following take-home points can be made based on data from six years of canine gastrointestinal biopsy submissions to the Angell biopsy service:

- Adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, and sarcoma (with a notable number of GISTs) were the most common malignancies diagnosed in the canine GI tract.

- Epithelial tumors predominated in the stomach, while carcinoma and lymphoma were diagnosed with equal frequency in the small intestine.

- Sarcoma was diagnosed more frequently than carcinoma and lymphoma in the large intestine, with the greatest proportion of GISTs occurring in the cecum.

- Grossly, adenocarcinoma tends to be annular and firm; lymphoma is also circumferential but homogeneously tan; sarcoma is firm and eccentric.

For information on the cytology of canine GI neoplasia, please refer to “Cytologic Diagnosis of Canine Gastrointestinal Neoplasia via Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration” by Angell’s Patty J. Ewing, DVM, MS, DACVP (Anatomic and Clinical Pathology). Angell’s Pathology Service can be reached at 617-541-5014 or pathology@angell.org.

References

- Willard MD. Alimentary neoplasia in geriatric dogs and cats. Vet Clin Small Anim 2012;42:693-706.

- Coyle KA and Steinberg H. Characterization of lymphocytes in canine gastrointestinal lymphoma. Vet Pathol 2004;41:141-146.

- Frank JD, Reimer SB, Kass PH, Kiupel M. Clinical outcomes of 30 cases (1997-2004) of canine gastrointestinal lymphoma. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2007;43:313-321.

- Rassnick KM, Moore AS, Collister KE, et al. Efficacy of combination chemotherapy for treatment of gastrointestinal lymphoma in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2009;23:317-322.

- Maas CPHJ, ter Haar G, Van der Gaag I, Kirpensteijn J. Reclassification of small intestinal and cecal smooth muscle tumors in 72 dogs: clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical evaluation. Vet Surg 2007;36:302-313.

- Russell KN, Mehler SJ, Skorupski KA. Clinical and immunohistochemical differentiation of gastrointestinal stromal tumors from leiomyosarcomas in dogs: 42 cases (1990-2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007;230:1329-1333.

- Hayes S, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Gregory-Bryson E, Kiupel M. Classification of canine nonangiogenic, nonlymphogenic, gastrointestinal sarcomas based on microscopic, immunohistochemical, and molecular characteristics. Vet Pathol 2013;50:779-788.