-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

Chickens are often underestimated in their capabilities, especially when compared to mammals, which often have more human-like features. However, when studied in their natural environments, chickens show great intelligence and have social hierarchies as sophisticated as those formed by dogs and other mammals.

Laying Hens

Laying hens are some of the most abused animals in all of farming. While more and more states are instituting farm animal confinement bans, the large majority of chickens live their lives in a space less than the area of a single sheet of paper.

The Life of a Battery Caged Hen

Laying hens are born in commercial hatcheries where they are hatched by the thousands in industrial incubators. Male chicks, unable to lay eggs and of a different strain than broiler chickens, are killed shortly after hatching because they are profitless for the industry. They are typically ground up alive, gassed, or disposed of in dumpsters. Hundreds of millions of male chicks are killed by the egg industry annually.

Most hens are beak-trimmed, a process deemed necessary by the egg industry to decrease cannibalism and other aggressive tendencies, and to reduce feed costs by preventing the flicking of food. The procedure, performed without anesthesia, involves slicing off the tip of young chicks’ beaks with a hot blade or infrared.

Not only is the procedure itself inhumane, but beak trimming also causes many physiological changes that prevent birds from expressing natural behaviors. A chicken’s beak is a sensitive structure that provides important sensory feedback (see Learn More link below). Food and water intake and preening behaviors are commonly reduced in birds following this procedure, and chickens are often in chronic pain from damage to sensory receptors. Although complete debeaking is not allowed in order to comply with some animal welfare rating programs (see below), the “Certified Humane” label still allows beak trimming under strict guidelines.

The female chicks, called hens, spend their lives (usually less than two years) confined in battery cages, in one 61-square-inch spot. They are unable to perform any natural behaviors, such as nesting, bathing, perching, or spreading their wings. On average, each hen lays 275-280 eggs per year.

The female chicks, called hens, spend their lives (usually less than two years) confined in battery cages, in one 61-square-inch spot. They are unable to perform any natural behaviors, such as nesting, bathing, perching, or spreading their wings. On average, each hen lays 275-280 eggs per year.

As the hens age, their egg production naturally slows. To increase production, the hens are forced to molt (shed their feathers) through starvation or the use of low-nutrient food until 20-25% percent of their body fat is lost. Hens are purposefully starved for up to two weeks during which lead to the onset of aggressive behaviors like feather-plucking. Returning their diet to normal rejuvenates of egg production, resulting in larger, and therefore more profitable eggs.

After their first or second laying cycle, depending on the use of forced molting, hens are slaughtered. While the practice of forced molting is prohibited by the EU, no federal law in the U.S., including the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act or the Animal Welfare Act, no federal law, including the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act or the Animal Welfare Act, currently sets any welfare standards for birds. Thus, chickens can legally be raised and slaughtered through any methods. Most producers opt not to slaughter the hens on-site, and they transport the hens to off-site slaughterhouses. If the hens survive the journey, they are often killed with full consciousness.

On the Farm

The battery cage, a popular choice among American conventional farmers, is home for millions of chickens, forcing them into an unnatural and stress-inducing environment. A typical farm contains thousands of battery cages, each housing three to ten hens with an average space allowance of 61 square inches for each bird. Thanks to the work of animal-welfare activists, the amount of hens in battery cages dropped from 95% in 2008 to less than 70% in 2023. To contrast, there are multiple types of cage-free housing, which accounted for 40% of the U.S. flock in March 2024. Barn systems, which can either be single or multi-level, allow birds to move freely indoors. These barns, especially when multi-leveled, provide hens with the ability to perch, nest, and bathe in dust, behaviors that are impossible in the confines of battery cages. Free-range hens have both the protection of a barn and the access to the outdoors necessary to perform these natural behaviors.

While cage-free hens escape the inhumane conditions inherent in battery cages, these facilities cannot always be considered cruelty-free. Hens’ abilities to express these natural behaviors are great improvements, but other inhumane farming practices must be addressed. Cage-free farms still buy their hens from hatcheries that kill male chicks at birth, and the hens are still subjected to the procedure of beak trimming or debeaking to lessen the effects of aggression. Forced molting continues to be a common practice in the U.S. Finally, the lifespans of laying hens across the spectrum rarely surpass two years, whereas hens in their natural environment would live upwards of ten years.

Physical/Behavioral Effects

The use of battery cages, and the practice of factory farming in general, causes numerous physical disorders in hens. The inability of hens to move in their cages not only inhibits their natural inclinations toward nesting, perching, and bathing, but also causes physical pain. They suffer from bone weakness and breakage, and numerous diseases including Fatty Liver Hemorrhagic Syndrome, the major cause of death in laying hens. In normal conditions, hens frequently bathe in dust to promote healthy feathers. On most egg farms, hens display “dustbathing” behaviors against the sides of the wire cages, leading to feather loss. Without the space to nest properly and with the added stress of artificial lighting, laying hens are highly susceptible to uterine prolapse, a condition in which the uterus is pushed outside the hen’s body. The average hen produces 260 eggs per year; without the protection of nests, the birds are completely exposed after each lay.

Psychological Effects

Not being able to nest inflicts significant psychological suffering on hens. Hens prefer litter and protection for nesting, which battery cage housing does not allow for. Unable to find privacy for laying in the confines of battery cages, hens will crawl over and under other hens to search for cover and nesting materials, increasing psychological stress. Hens will often pace and throw themselves against the metal sides of the cages, which is symptomatic of severe frustration. The absence of perches in battery cages also interferes with the natural disposition of laying hens to form hierarchies, potentially increasing aggression.

In the Slaughterhouse

Once the hens reach the end of their laying cycle, they are killed, either on the farm, or in a slaughterhouse. The process of catching the hens is both psychologically stressful and physically abusive. Human handling is a known stressor for hens, and the battery cages do not allow for easy removal. Hens are often held seven at a time in the hands of catching teams, and their legs and wings are often torn and broken when they are being removed. Since only a few processing plants in the U.S. accept spent hens, these birds must endure long distances on overheated trucks to get to the slaughterhouses. Many die from congestive heart failure due to the stresses of handling and transport.

During slaughter, laying hens are not protected by federal regulations such as the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act. They do not have to be rendered senseless before they are killed. In the processing plant, hens are shackled by their legs and hung upside-down. They are often stunned through the use of an electric water bath, but this method is not perfect. Many chickens are not successfully rendered unconscious prior to slaughter, and are burned and/or drowned alive.

Many hens are slaughtered without being stunned at all. The hens’ throats are slit on a circular blade before being placed in a scalding tank, meant to loosen their feathers. If they are not properly stunned, they often miss the blade. This means that the hens enter the tank conscious and are boiled alive. More humane alternatives, such as Controlled Atmospheric Stunning (CAS), or gas stunning, are being developed and increasingly used in Europe, but it is often difficult to implement these large-scale industry changes.

The Future of Battery Cages

Many U.S. states (Arizona, California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, and Washington) have passed restrictions on the extreme confinement of egg-laying hens:

- 2008: California overwhelmingly passed The Prevention of Farm Animal Cruelty Act. This Act phased out the use of battery cages, gestation crates, and veal crates in California farms.

- 2009: Michigan’s legislature passed a ban on battery cages that included a 10-year phase out.

- 2009: Ohio placed a moratorium on new battery cages effective September 29, 2010.

- 2011: Oregon and Washington passed legislation to transition commercial egg farms to enriched colony systems.

- 2016: Massachusetts passed a ballot measure prohibiting egg-laying hens, breeding pigs, and veal calves from inhumane confinement.

- 2018: California strengthened its cage and crate-free standards for laying hens, mother pigs and veal calves, and expanded the in-state sales ban to also include pork and veal products.

- 2018: Rhode Island banned extreme confinement of egg-laying hens.

- 2019: Washington state banned the in-state sale of products from battery cage systems.

- 2019: Michigan banned battery cages and sets requirements for available space, enrichment, and banning the sale of products that don’t reach their standards.

- 2020: Colorado eliminates cage confinement of egg-laying chickens and requires that eggs produced and sold in the state be cage-free; it also requires enrichments.

- 2021: Utah mandated cage-free conditions and more space for each bird by 2025 and requireds enrichments that are vital to the hens’ psychological and physical well-being, including perches, nest boxes, and areas designed for scratching and dust-bathing.

- 2021: Nevada became the becomes 9th state to ban cages for egg-laying hens, and mandatinges enrichments which give hens the ability to engage in vital natural behavior like perching, scratching, dust bathing and laying eggs in a nest.

- 2021: Massachusetts updated and strengthened previous legislation to define specific dimensions that laying hens must be afforded.

- 2022: Arizona’s Department of Agriculture promulgates regulations Arizona passed legislation to phase out the use of that ban cruel cages for egg-laying hens and ensure that all eggs produced and/or sold in the state are cage-free.

- 2023: New Jersey legislation banned the use of battery cages, gestation crates, and veal crates.

Additionally, in response to consumer demand, many grocery chains and companies are converting to cage-free egg suppliers.

Learn more:

- Beak trimming of poultry: its implication for welfare, World’s Poultry Science Journal, 2007.

- Table Egg Production and Hen Welfare: Agreement and Legislative Proposals, Congressional Research Service, 2014.

- 2025 Is A Critical Year For Cage-Free Meat And Eggs, Forbes. 2025.

More than Meat: The Lives of Broiler Chickens

In the United States, more than nine out of every ten land animals killed for meat are “broiler” chickens. Professor Emeritus John Webster at the University of Bristol calls the broiler industry the “single greatest example of human inhumanity toward another animal.” Most broiler chickens’ lives consist of continuous abuse, from the farm to the slaughterhouse. Due to their small size, chickens make up the vast majority of farmed animals killed and yet no federal law includes protections for chickens.

On the Farm

“Factory farms,” known for raising large amounts of animals in minimal amounts of space, bred over 9 billion broiler chickens a year, as of 2023, in the United States. These chickens spend their lives in warehouse-like sheds, stocked in such high-densities that they are denied many important natural behaviors, such as the abilities to nest, roost or even flap their wings.

These sheds, called “grower houses,” confine up to 20,000 chickens at a density of approximately 130 square inches per bird, compared to the 288 square inches recommended per bird. Grower houses are usually windowless buildings with rows of feeders and drinkers as well as sparse amounts of little on the ground. Temperatures are often controlled through forced-ventilation. As a result, these sheds greatly frustrate broiler chickens. Many chickens will die from disease and stress related to these overcrowded conditions; however, profit margins encourage the continued use of grower houses.

The Life of a Broiler Chicken

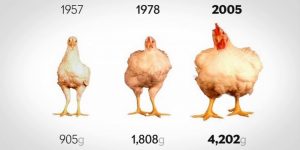

Most “broiler” chickens are selectively bred in order to produce the most meat on a bird in the shortest period of time and using the least amount of feed necessary. Modern broiler chickens reach market weight in only 6 weeks. Daily growth rates have increased over 300% in the past 50 years from an estimated 25 to 100 grams per day.

Although selective breeding practices increases productivity, the industry practice severely harms the welfare of broiler chickens. At six weeks of age, most broiler chickens have such difficulty supporting their abnormally large body weights that they spend almost 90 percent of their time lying down. Lying in waste can cause skin irritation and burns due to the ammonia exposure, inflicting pain. Selective breeding can also lead to lameness and other fatal defects such as respiratory disease, big liver and spleen disease, weakened immune systems, ascites, and acute death syndrome. Ascites, a condition in which the heart and lungs do not have the capacity to support an overgrown body, is common in broiler chickens. Broilers are the only livestock that are in chronic pain for the latter part of their lives, a result of selective breeding that severely damages their joints.

Some chickens are born to be broiler “breeders.” Unlike broiler chickens who are slaughtered around 7 weeks old, broiler breeders live between 1-2 years despite having the same genetic predisposition for fast growth, as well as the painful conditions of lameness and heart disease. To limit their growth rate, breeders are fed only a quarter to half of the amount of food of broiler chickens, leading to undernourishment and nutritional deficiencies. If provided an unrestricted diet, most breeders would not survive more than one year. Breeders are also limited to as little as six hours of light per day, to both reduce costs and control the age of sexual maturity. The darkness not only increases stress and frustration, but often causes blindness in the birds.

To reduce the aggressive behaviors exhibited due to confinement, breeder chickens often have their beaks trimmed and toes removed. Male breeders additionally have their combs removed in a process called “dubbing.” These surgeries are usually performed without anesthesia. The leg deformities and skeletal disorders that develop before death in broiler chickens become life-long conditions for breeders, as they are kept alive much longer than their offspring. These conditions can become so severe that almost 50 percent of breeders must be slaughtered prematurely due to complete lameness or infertility.

Physical/Behavioral Effects

The environment created by grower houses is detrimental to the physical well-being of broiler chickens. The confinement of a large number of chickens in inadequate space results in the rapid deterioration of air quality within the sheds. Chicken excrement accumulates quickly on the floors. As bacteria break down the litter, the air becomes polluted with ammonia, dust, and fungal spores. High ammonia levels can cause painful skin conditions, respiratory problems, pulmonary congestion, swelling, hemorrhage, and blindness. Ammonia also destroys the cilia in the chickens responsible for preventing other bacteria from being inhaled. During winter, when the ventilators are closed to conserve heat, ammonia levels may reach 200 parts per million; healthy ammonia levels should never surpass 20 parts per million.

Psychological Effects

Broiler chickens typically live in overcrowded conditions, leading to increased stress and frustration. Grower sheds are often stocked to the extent where broilers cannot stand, turn around, or spread their wings. The ammonia levels created by the poor ventilation in grower houses limit the broiler chickens’ sense of smell, rendering them unable to truly perceive their environments.

In the Slaughterhouse

Broiler chickens spend an average of 45 days in the grower sheds. Once they have reached market weight, they are transported to outside facilities for slaughtering. For the birds, the journey to the slaughterhouse is physically and psychologically abusive. Catching teams load the chickens at rates of up to 1,500 birds an hour, injuring many in the process. From dislocated hips and broken wings to internal hemorrhaging, the chickens suffer due to rough handling from this fast-catching rate. During transport, the chickens are denied food, water, and shelter for many consecutive hours. The crates are often improperly covered, and the birds are exposed to high winds and cold temperatures. The unfeathered parts of their bodies become red and swollen, and sometimes even develop gangrene. Many chickens die during the trip from hypothermia, or from heart failure associated with stress.

Similar to laying hens, broiler chickens are not protected by federal regulations during slaughtering. Many alternatives to these inhumane slaughterhouse practices exist, from the use of mechanical harvesting or herding, to a more caring, gentler way of manually catching chickens.

Environmental Consequences

The waste from broiler chicken factory farming has serious environmental consequences.

Learn more:

Super-size Problem, The Humane Society of the United States, 2017.

A Growing Problem, Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry: The Case for Slower growth, ASPCA, 2015.

Did You Know?

- Chickens in a flock recognize each other by facial features, remembering more than 100 individual chickens. They prefer to avoid unfamiliar birds.

- Hens have an innate need to nest. A major source of frustration for caged hens is not having any access to nesting materials. This frustration can cause injurious behavior like feather-pecking.

- A mother hen begins bonding with her offspring long before they have hatched, turning the eggs more than five times an hour and clucking to the unborn chicks.

- Chickens have complex vocalizations. They will emit a different alarm call if a predator travels by air than by land.

- The flock coordinates its activities so each chicken bathes, eats, and nests together.

- The sensitive beaks of chickens are much like our hands, used to feed, to pick up items, and to explore their environments. It is common practice to cut off the sensitive tip of the beak with no pain relief in a common, but cruel, industry practice called “beak trimming.”