-

Adopt

-

Veterinary Care

Services

Client Information

- What to Expect – Angell Boston

- Client Rights and Responsibilities

- Payments / Financial Assistance

- Pharmacy

- Client Policies

- Our Doctors

- Grief Support / Counseling

- Directions and Parking

- Helpful “How-to” Pet Care

Online Payments

Emergency: Boston

Emergency: Waltham

Poison Control Hotline

-

Programs & Resources

- Careers

-

Donate Now

By Steven Tsai, DVM, DACVR

By Steven Tsai, DVM, DACVR![]()

angell.org/diagnosticimaging

diagnosticimaging@angell.org

617-541-5139

April 2025

X

Lower urinary tract disease is a common presentation for dogs and cats in all areas of companion animal care. Common causes of lower urinary tract disease include urolithiasis, urinary tract infection, or neoplasia. This article will focus on radiographic evaluation of the lower urinary tract – urinary bladder, urethra, canine prostate – especially as commonly encountered in a general practice setting. This article will not cover positive or negative contrast urinary tract procedures; these procedures are more appropriately performed in an emergency or specialty setting with videofluoroscopy.

Normal Anatomy

The urinary bladder can exhibit a wide range of sizes in normal patients. When empty, the bladder is often not visible at all, and when distended, it can occupy nearly the entire caudal abdominal volume. There is no defined upper limit to the size of a normal urinary bladder, although it is rare for the bladder to extend cranially to the umbilicus. In dogs, the bladder can extend slightly into the pelvic canal, while in cats it is usually entirely abdominal in location.

Figure 1: Lateral radiograph of an intact male dog with an indwelling urinary catheter, delineating the course of the normal urethra (magenta arrowheads) as well as a normal-sized prostate gland (green arrows). The patient also has numerous calculi in the bladder and urethra.

In intact male dogs, the prostate gland is usually visible as a smooth, round soft tissue opacity at the pelvic inlet. A normal prostate is generally less than 70% of the height of the pelvic inlet (defined as a line drawn between the cranioventral tip of the sacrum and the pubic brim).1 In neutered male dogs, the prostate is typically not visible radiographically.

The urethra is typically not visible radiographically but extends directly caudal from the bladder through the pelvic canal. In cats and female dogs, the urethra terminates caudal to the pelvis in the perineal region, while in male dogs, the urethra courses ventrally after emerging from the pelvic outlet, extending through the penis ventral to the os penis. (Figure 1)

Bladder Abnormalities

The most common bladder abnormalities encountered in canine and feline patients are cystitis, urocystolithiasis, or neoplasia. Cystitis could be infectious or sterile/idiopathic, but generally, there is no radiographically detectable sign of cystitis. One exception is emphysematous cystitis, which is most commonly seen in patients with diabetes mellitus, in which glucosuria predisposes to infection with anaerobic gas-producing bacteria. As the infection is often found within the bladder wall, radiographically, there can be an irregular gas rim associated with the bladder. (Figure 2)

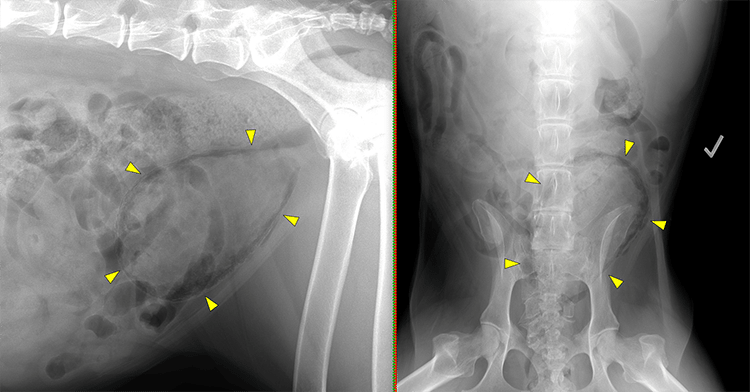

Figure 2: Lateral and ventrodorsal radiographs of a diabetic patient with emphysematous cystitis. Note the irregular peripheral gas lucencies associated with the bladder, indicating intramural emphysema secondary to infection with gas-producing bacteria (yellow arrowheads).

Classically, urinary calculi have been divided into those that are of a mineral composition and therefore radiopaque vs. those that are non-mineral and therefore radiolucent. The radiopaque composition calculi are calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, or struvite, while the radiolucent stones are urate or cystine. A few recent studies have shown, however, that on modern digital radiography systems, urate and cystine stones are often detectable. One study in an in vitro setting using phantoms found that nearly all urate and cystine stones larger than 1 mm are visible radiographically.2 A second study in a clinical setting found that 85% of urate and 92% of cystine stones were visible on radiographs before stone removal.3

Bladder calculi can range from amorphous sediment to tiny sand-like foci to variably spiculated or smooth stones, which occur singly or in clusters. Care should be taken not to over-interpret the presence of mineral calculi in the urinary bladder if there are also intestinal segments (especially the colon) superimposed on the bladder. A useful technique for isolating the bladder during a lateral radiographic exposure is to apply compression over the bladder using a radiolucent wood or plastic paddle (the hand holding the paddle should be in a leaded glove, of course). The compression will push intestinal segments away from the bladder, and the mineral calculi should be visible through the radiolucent paddle. (Figure 3)

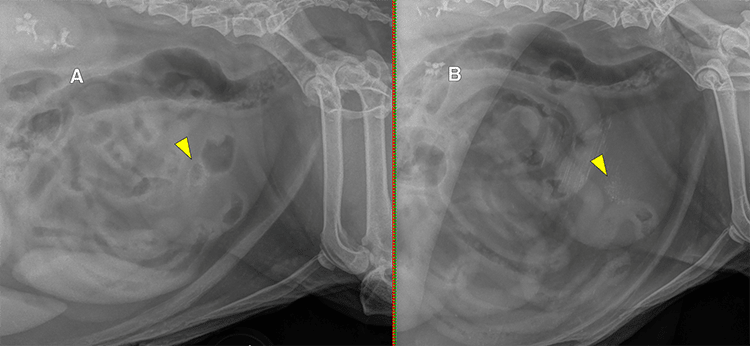

Figure 3: Lateral radiographs without (A) and with (B) lateral compression of the bladder with a wooden paddle in a patient with granular mineral cystic calculi (yellow arrowheads). While the mineral calculi are visible at the center of the bladder without compression, there are multiple intestinal segments also superimposed on the bladder. Paddle compression displaces the intestinal segments away from the bladder, allowing for definitive identification of calculi within the bladder (unfortunately, the paddle we use at Angell is somewhat old and dirty, resulting in some additional mineral opaque streaking).

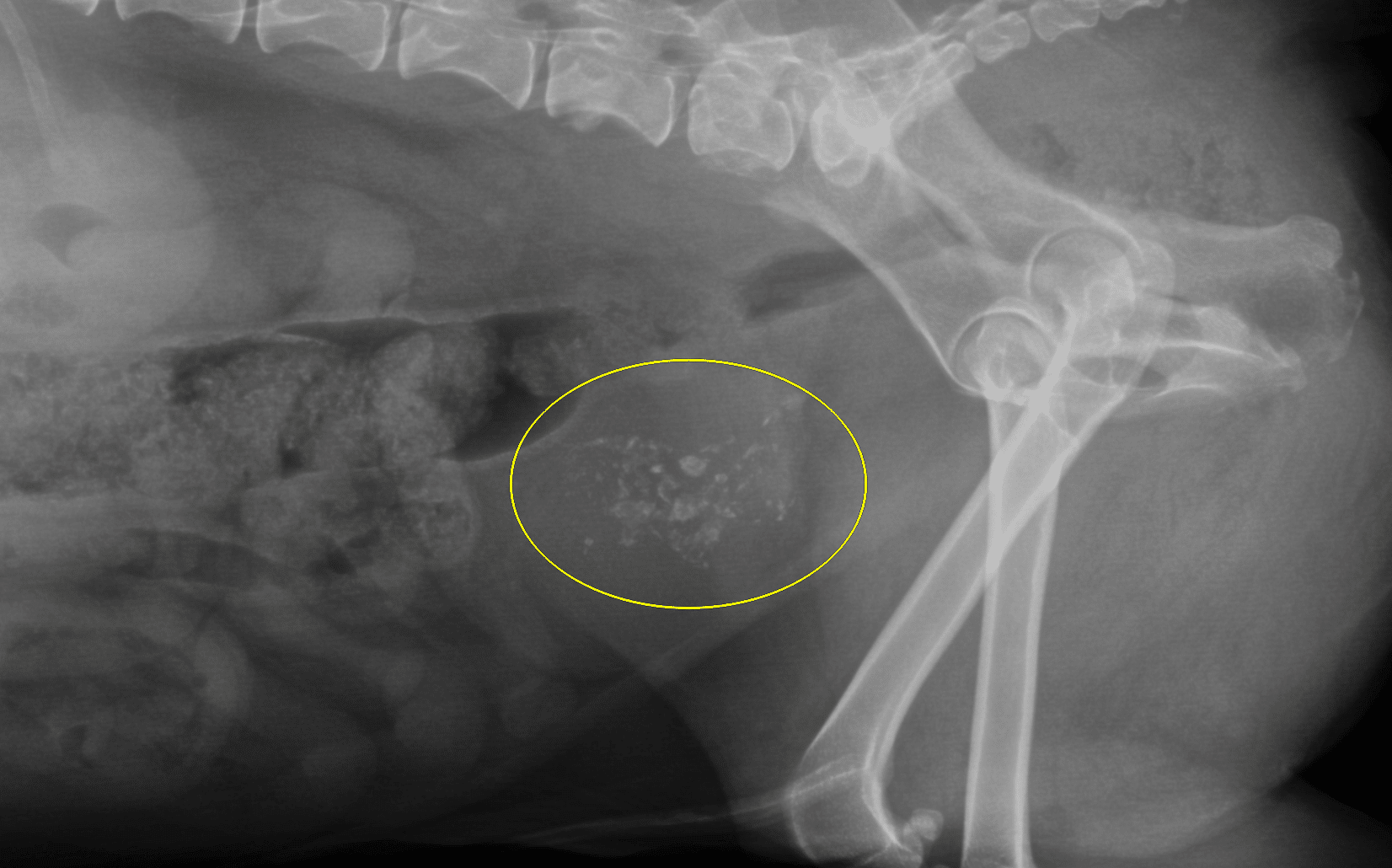

The overwhelming majority of cancerous bladder lesions are transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). While squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and various soft tissue sarcomas are also reported, in my experience, these are vanishingly rare. TCC most commonly arises from the region of the trigone, along the dorsal aspect of the bladder neck. However, it can arise from anywhere along the mucosal surface of the lower urinary tract. Mineralization significantly raises the degree of concern for malignancy. Radiographically, most bladder mass lesions are not detectable unless they are mineralized, since fluid and soft tissue have the same opacity. (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Lateral radiograph in a patient with a large mineralized bladder transitional cell carcinoma (yellow circle). Note the irregular shapes of the mineral opacities, which are more typical of dystrophic mineralization rather than urolithiasis. Ultrasound or CT is generally necessary to differentiate a mineralized mass from urolithiasis, however.

Urethral Abnormalities

Similar to the bladder, the most commonly encountered abnormalities of the urethra include urethrolithiasis, urethritis, and urethral neoplasia. Generally speaking, urethritis and urethral neoplasia will not be detectable on plain radiographs. While urethral TCC does occur, clinical signs of stranguria would typically begin long before the mass is large enough to exhibit mineralization.

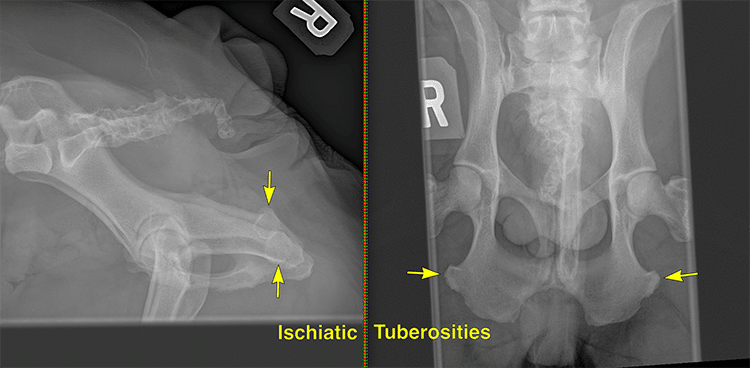

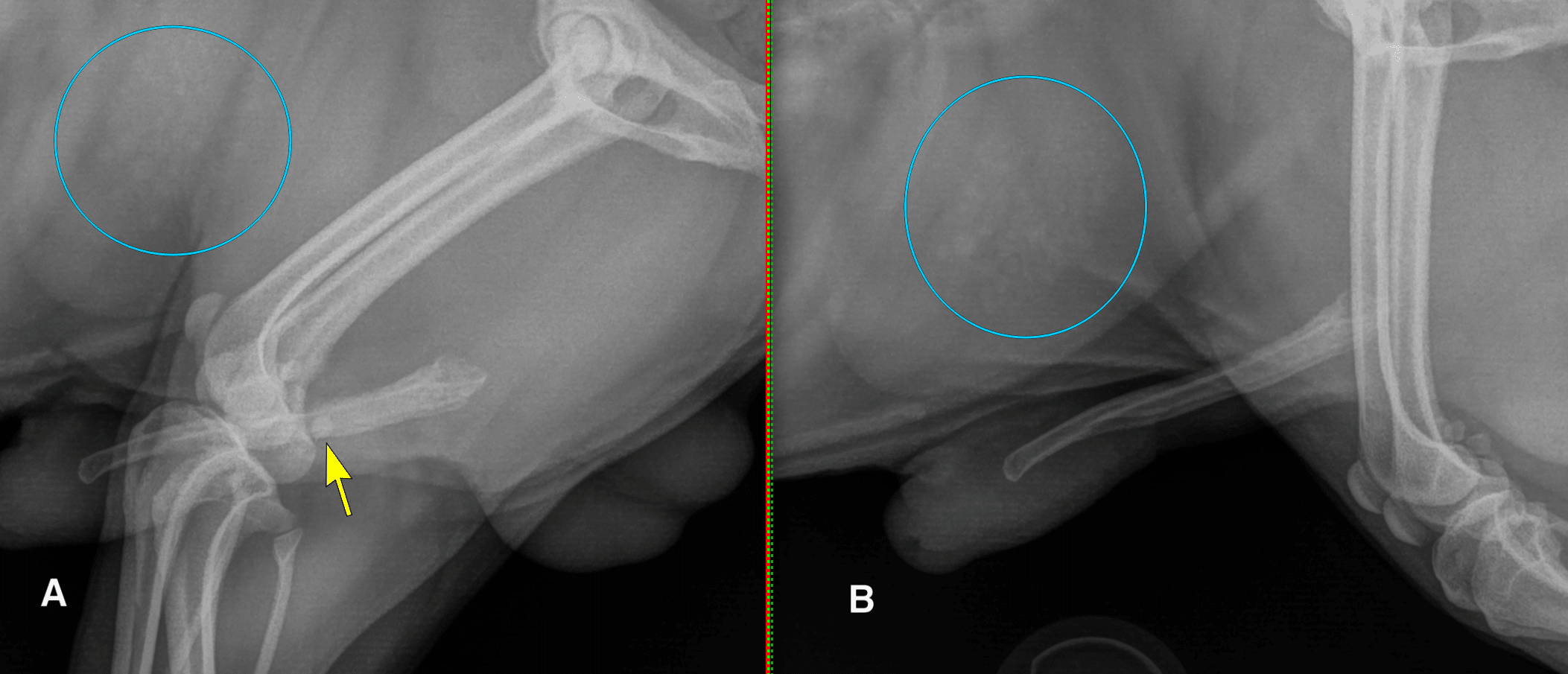

Urethral calculi can be found along any location of the urethra, from the proximal portion cranial to the pubis, to the intrapelvic portion of the urethra, to the more distal part of the urethra caudal to the pelvis in cats and female dogs, and along the entire length of the penile urethra in male dogs. In dogs, it is important not to mistake the ischiatic tuberosities of the pelvis for large urethral calculi on lateral projections (Figure 5). It can also be helpful to obtain a lateral radiograph with one leg raised/abducted to reduce superimposition in the pelvic canal (Figure 6). In male dogs, the most common location for urethral calculi is at the level of the proximal portion of the os penis, as the os penis creates a relative resistance to urine flow. It is usually recommended to obtain lateral views of the penile urethra in male dogs with the pelvic limbs at different degrees of flexion to ensure urethral calculi are not being obscured by the femurs or stifles (Figure 7). Sesamoids in the stifle region (fabellae and popliteal sesamoids) can also be superimposed with the urethra, perfectly mimicking calculi. Having at least two radiographs with the legs in different positions ensures that sesamoids are not misinterpreted as urethral calculi (Figure 8).

Figure 5: Lateral and ventrodorsal radiographs in a female dog. On lateral views, the ischiatic tuberosities (yellow arrows) create distinct round mineral opacities that superimpose with the course of the urethra.

Figure 6: Lateral radiographs of a patient with pelvic limbs neutral (A) and with one leg raised/abducted (B). A round mineral calculus is present in the bladder, visible on both radiographs (green arrowheads). A smaller round mineral calculus is present in the distal pelvic urethra, visible only with the leg raised (magenta arrow).

Figure 7: Lateral radiographs of a male dog with the pelvic limbs neutral (A) and flexed (B). An oblong mineral calculus in the penile urethra is obscured by the femurs on the neutral view but revealed with the femurs positioned more cranially (orange arrowhead).

Figure 8: Lateral radiographs of a male dog with the pelvic limbs flexed (A) and neutral (B). With the legs bent, the stifles are superimposed with the penis, and a fabella is perfectly positioned to mimic a urolith in the penile urethra (yellow arrow). Note that this patient also has several cystic calculi, some of which are of a similar size and shape to the fabella (blue circles).

Prostatic Abnormalities

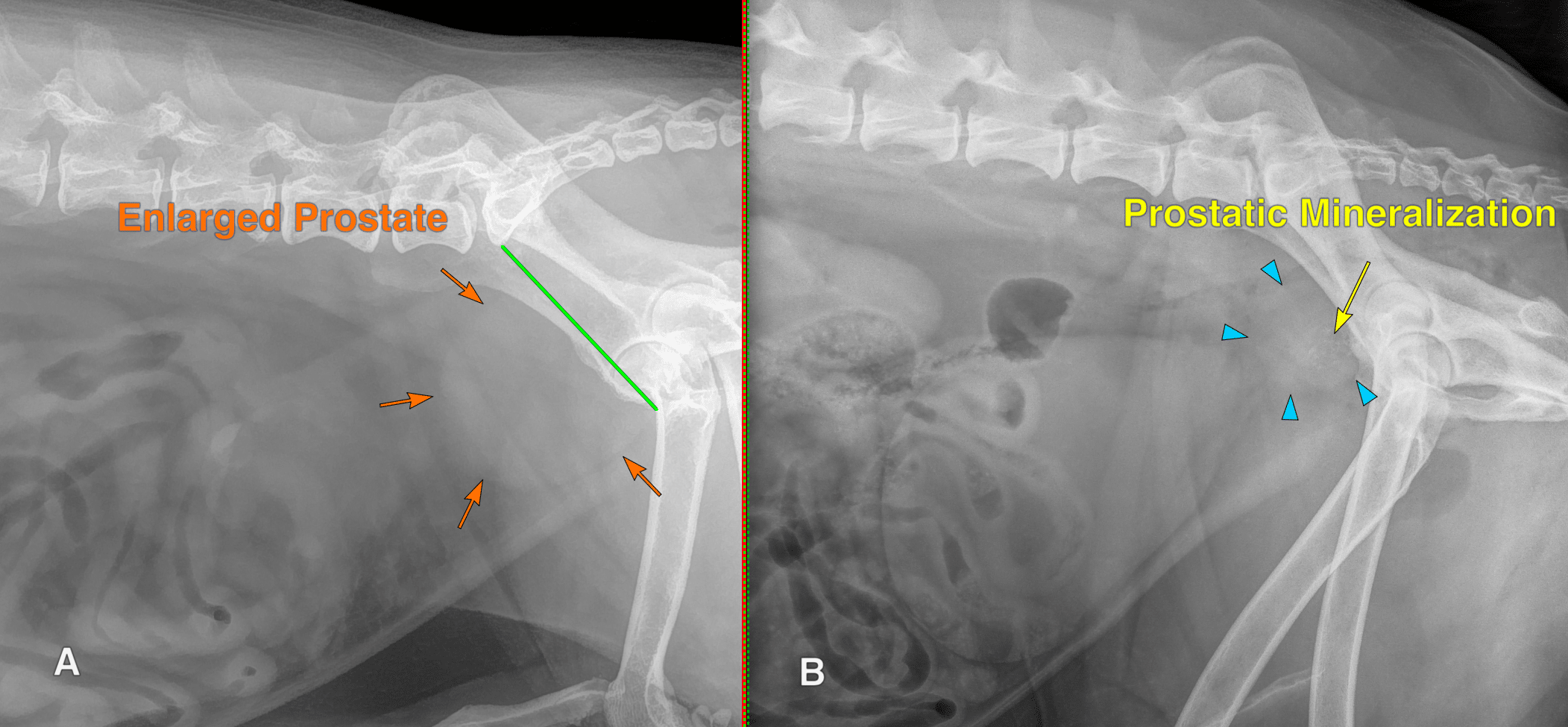

Although the prostate gland is not technically part of the urinary system, it completely encircles the proximal urethra in male dogs. It is therefore often implicated in lower urinary tract abnormalities. As noted above, a normal prostate is generally considered to be less than 70% the height of the pelvic inlet. It should be noted, however, that the prostate gland normally increases in size with age in intact male dogs, and there is no strict pathologic delineation between a normal prostate and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). It should be presumed that all intact males will develop BPH given enough time, and prostatomegaly itself should not be viewed as pathologic unless correlated with clinical symptoms. Generally speaking, there is no radiographic way to differentiate BPH from prostatitis or prostatic abscessation. (Figure 9)

Figure 9: (A) Lateral radiograph of an intact male dog with prostatomegaly. There is a smooth, round soft tissue opacity at the pelvic inlet (orange arrows), which measures approximately 85% of the height of the pelvic inlet (green line). This patient has benign prostatic hyperplasia. (B) Lateral radiograph of a castrated male dog with an enlarged prostate (blue arrowheads) that exhibits dystrophic mineralization (yellow arrow). This patient has prostatic transitional cell carcinoma.

Neutered male dogs have a higher risk of prostatic neoplasia than intact male dogs. The most common forms of prostatic neoplasia are TCC or prostatic adenocarcinoma. The prostate gland is typically not visible at all in neutered male dogs; anecdotally, they usually measure between 1 and 2 cm in thickness. Any rounded soft tissue structure in the location of the prostate in a neutered male dog should raise some concern for prostatic neoplasia. Similar to bladder masses, mineralization of the prostate raises significant concern for cancer, with one study showing 100% positive predictive value for malignancy in mineralized prostate lesions in neutered males.4 (Figure 9)

Prostatic Cysts

In intact male dogs, prostatic cysts can develop either within the parenchyma or adjacent to the parenchyma. Intraparenchymal cysts, previously called retention cysts, are thought to arise from obstruction of prostatic ducts due to BPH, resulting in the accumulation of prostatic secretions. Extraparenchymal cysts, previously called paraprostatic cysts, are classically believed to be formed from Müllerian duct remnants, although this theory remains unproven. Intraparenchymal prostatic cysts are generally not detectable radiographically.

Extraparenchymal prostatic cysts can be pretty small and subclinical, but they can also enlarge to quite a dramatic size (Figure 10). Radiographically, extraparenchymal cysts can resemble a moderately full urinary bladder, thus giving the radiographic impression of two urinary bladders. The walls of extraparenchymal prostatic cysts can also exhibit thin mineralization. The cysts are usually located cranial to the prostate, but they can also project caudal to the prostate into the perineal region. Clinical signs can therefore include fecal retention. Complete surgical removal of extraparenchymal cysts +/- castration is the treatment of choice.

Figure 10: Lateral radiographs in two male dogs with extraparenchymal (a.k.a. paraprostatic) cysts. (A) This patient exhibits large (blue arrows) and small (yellow arrowheads) ovoid soft tissue opacities in the caudal abdomen, creating the impression of two urinary bladders. Note that without mineralization of the cyst wall, it is not possible to differentiate radiographically between the bladder and the prostatic cyst. (B) This patient exhibits a large extraparenchymal prostatic cyst, which has faintly mineralized walls (orange arrows). Note that extraparenchymal prostatic cysts can extend caudally through the pelvic canal, causing symptoms of straining to defecate and/or perineal swelling.

Summary

Radiographic evaluation of the lower urinary tract remains a core competency for veterinarians in modern companion animal primary care practice. Detection of radiopaque urolithiasis is shown to be improved in modern digital radiography systems, with up to 85-100% of urate and cystine stones — previously thought to be radiolucent — being visible on plain radiographs. Radiographs of the urethra with the legs in different positions may be necessary for accurate detection of calculi. Mineralized lesions in the bladder wall and prostate (especially in neutered male dogs) raise significant concern for malignancy and warrant further investigation. Extraparenchymal prostatic cysts in male dogs can present with lower urinary symptoms or signs of constipation, and surgical treatment is preferred.

References

- Atalan G, Barr FJ, Holt PE. Comparison of ultrasonographic and radiographic measurements of canine prostate dimensions. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1999 Jul-Aug;40(4):408-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.1999.tb02133.x. PMID: 10463836.

- DeBow P, Auger M, Fazio C, Cline K, Zhu X, Lulich J, de Swarte M, Lamb D, Hespel AM. The most common types of uroliths larger than 1 mm are readily visible and accurately measured in an in vitro setting mimicking the canine abdomen using digital radiography. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2023 Sep;64(5):806-812. doi: 10.1111/vru.13268. Epub 2023 Jul 16. PMID: 37455335.

- Andrews C, Williams R, Arjoonsingh A, Vilaplana Grosso FR. Cystine and urate cystoliths in dogs are frequently visible on radiographs prior to surgical or nonsurgical removal. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2024 Jul 26;262(10):1338-1342. doi: 10.2460/javma.24.05.0302. PMID: 39059429.

- Bradbury CA, Westropp JL, Pollard RE. Relationship between prostatomegaly, prostatic mineralization, and cytologic diagnosis. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2009 Mar-Apr;50(2):167-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2009.01510.x. PMID: 19400462.